How the Know Nothing Party Turned Nativism into a Political Strategy

In the 1840s and '50s, Secretive Anti-Immigrant Societies Played on National Fears Fed by the Spread of Slavery

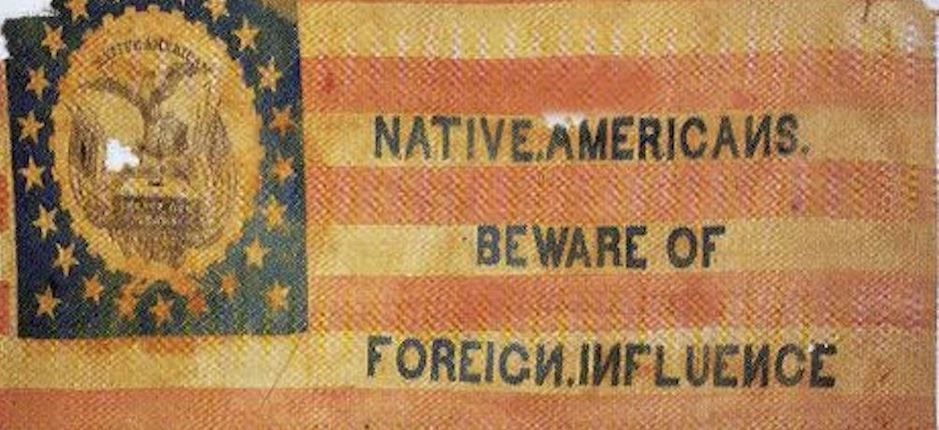

Flag of the Know Nothing or American party, circa 1850. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Though the United States is a nation built by immigrants, nativism—the fear of immigrants and the desire to restrict their entry into the country or curtail their rights (or both)—has been a central strain in the national fabric from the beginning. Nativism waxes and wanes with the tides of American culture and politics, with some eras exhibiting more virulent anti-immigrant activism than others.

But few eras have exceeded the 1840s and 1850s, when a ferociously anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, and xenophobic secret society grew into a nativist political entity called the Know Nothing Party and briefly dominated the politics of a handful of states by stirring up violent outbursts before imploding over the slavery issue in 1855.

Though the United States always enjoyed robust immigration, it was not until the 1840s and 1850s that it became a divisive issue in politics. The highest level of immigration in U.S. history (as a proportion of overall population) occurred in 1854, in the wake of the massive influx of people from Ireland and the German states. The Irish were desperate to escape the infamous “potato famine,” which struck in 1845, and the Germans were motivated by overpopulation and unemployment in their homeland.

Coastal cities, in particular New York, were the primary entry points for European immigrants, with Irish and Germans establishing their own neighborhoods, maintaining their ethnic identities, and becoming the new industrial working class. Many current residents, fancying themselves “natives” (with no sense of irony concerning actual Native Americans), were none too pleased, unfairly condemning the newly-arrived Americans as job-stealers, drunks, criminals, and—perhaps worst of all, to their way of thinking—Roman Catholics.

Religion was at the core of the fight over immigration in the 19th century. Though not all the Germans and Irish who disembarked in the antebellum period were Catholics, the majority were. Their arrival reignited the war between Protestants and Catholics that had played out in Europe over centuries. American Protestants viewed Catholics as a genuine threat to the republic, believing that their loyalty was to the Pope in Rome rather than the U.S. government. This wave of Catholic immigrants, nativists asserted, was a papal invasion aimed at overthrowing democracy and establishing a monarchy, not unlike the Catholic crowns of France and Spain.

Motivated by anti-Catholicism and perverted patriotism, nativist organizations sprouted in New York City and spread to Philadelphia in the 1840s. With such names as “Native American Democratic Association” and “Organization of United Americans,” they were, at first, semi-secret fraternal organizations concerned more with local matters and cultural camaraderie than with national politics.

In 1851, however, the state of Maine banned liquor, which sparked a controversy. Nativists, seeing their Catholic neighbors as drunkards (Irish and their whiskey, Germans and their beer), emphatically embraced temperance as a way to punish immigrant communities, and mobilized to spread the “Maine Law” to other states. Liberals and newly arrived immigrants, on the other hand, rejected state-imposed morality and fought to kill temperance legislation.

The emerging battles over temperance and immigration at the local and state levels were symptomatic of larger national crises, as the nation experienced a disruptive “industrial revolution” and a growing division over the spread of slavery. The two-party system of Democrats and Whigs, forged in the 1830s over such issues as banking policy and nullification, could not contain the passions unleashed by abolitionism, the Maine Law, and immigrant rights. In short, the 1850s were not the 1830s, and white Americans came to care more about slavery and immigration than banking and tariffs. Thus, the Second Party System fractured. Whigs collapsed after their Southern wing united with Democrats to push through the notoriously pro-slavery “Compromise of 1850,” while many Northern Democrats, appalled by the pro-Southern content of the so-called compromise, bolted their party. Invigorated by the influx of Whig enslavers, Democrats won Congress and the White House in 1852 and launched a bold pro-slavery agenda.

Northern Whigs and Democrats, meanwhile, found themselves in partisan limbo. Looking to demonstrate their outrage at Democratic pro-slavery policies, they flocked to their local nativist organizations. Enjoying the sudden influx of members, nativist organizers began to forge a national movement. In 1853, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner, New York City’s largest nativist organization, joined with the Order of United Americans, which had chapters along the East Coast, to form the “Know Nothings.”

The two-party system of Democrats and Whigs, forged in the 1830s over such issues as banking policy and nullification, could not contain the passions unleashed by abolitionism, the Maine Law, and immigrant rights.

Instead of being semi-secret and community-oriented, the Know Nothings were completely covert and dedicated to passing nativist legislation at the state and national levels. The origin of the appellation is unknown, but was probably concocted by the group itself as a reference to their mysterious nature. Know-Nothing “lodges” were established in almost every American city, with membership and meetings shrouded in secrecy. The plan was to infiltrate political parties, achieve elected office, and then push through temperance reforms and immigration restrictions.

Their plan was impressively underhanded and devious. Instead of running openly as “Know Nothings,” nativists campaigned for office as Democrats or Whigs, got on a regular party slate, and then, with the covert backing of their lodge, achieved election. Put another way, a town or city would not know they had elected Know Nothings until after the election had occurred. Needless to say, these tactics wreaked havoc among the parties, as Whigs and Democrats scrambled to find the hidden Know Nothings in their ranks. Adding to the confusion was the fact that the lodges operated almost independently of each other—there was no national leadership or coordination until 1855.

A series of unrelated events in the early 1850s served to boost nativist numbers. First, cities and towns experienced battles over the public funding of Catholic schools, enraging Protestants who hated to see their tax dollars help Catholic kids. Second, in 1853 Cardinal Gaetano Bedini, personal agent of the Pope, made a tour of the United States, raising suspicions of a papal plot. And third, Democratic President Franklin Pierce selected a Catholic to be postmaster general. The idea of Catholics controlling the mail made nativists apoplectic. Nativists took to the streets to vent their anger, attacking Catholic Churches and Catholic-associated businesses in small towns like Chelsea, Massachusetts as well as major metropolitan areas including Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Cincinnati.

Nativists easily preyed on popular passions and paranoia, and since they operated outside the normal partisan channels, they relied heavily on their populist appeal. Still, by May 1854, membership in the Know Nothings did not exceed 50,000—certainly not enough to shape national policy. With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that spring, previously free western territories were opened to the spread of slavery. With the Whig Party in the grave, more Northerners joined the Know Nothings to express their anger at the Democrats for passing the bill. By October 1854, membership had jumped to more than one million, and the Know Nothings seemed poised to replace the Whigs as the major opposition to the Democrats. Most Know Nothings embraced the anti-slavery movement for several reasons, including disgust with the Catholic Church’s long history with slavery, frustration with Democratic policies, and the belief that the Irish were pro-slavery. “The love of liberty in the Irish consists in the desire of freedom from oppression in their own persons, and the privilege of exercising tyranny over others,” wrote one resident of Maine to The Liberator. “I never saw one of the race since the anti-slavery movement commenced, who did not hate a negro.”

Local and congressional elections in the fall of 1854 were a mess, as voters had a confusing array of new and old parties to choose from and the Know Nothings enjoyed significant electoral gains, winning control of several states and sending a substantial number of men to Congress.

Despite their successes in 1854, however, the Know Nothings quickly fractured as slavery proved a more potent political issue than immigration. At their first national convention, held in June 1855 in Philadelphia, Know Nothings refashioned themselves as the American Party, but split between anti-slavery Northerners and pro-slavery Southerners. Throughout 1855 and 1856, “Americans,” as they called themselves, aligned with Republicans and Democrats in an attempt to keep immigration and nativism at the fore of national politics.

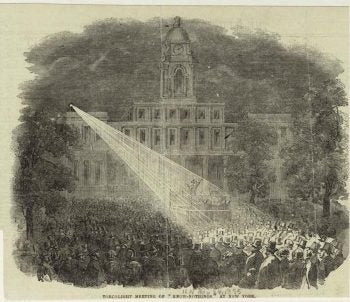

Illustration depicting a “Know-Nothing” demonstration in front of New York’s city hall (1855). Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Ultimately, they were unsuccessful. In 1856, they even launched an abortive White House run. Former President Millard Fillmore, a lifelong racist and xenophobe, campaigned under the banner “Americans Must Rule America.” To an audience at Rome, New York, he warned: “You should be thankful that you live in this free and happy land. Guard well your institutions, and be ever watchful against any attempt to divide or destroy your country.” To an American Party chieftain, he was more blunt: “I have for a long time looked with dread and apprehension, at the corrupting influence which the contest for the foreign vote is exciting upon our election.” Sadly for him, he carried only one state.

After the embarrassing Fillmore flop, Know Nothings learned to acquiesce to their subordinate position in their new partisan homes. In the free states, they joined with Republicans to fight the spread of slavery, and in the slave states they agreed with Democrats that the protection and expansion of slavery was paramount. The final American Party convention was held in Louisville, Kentucky in June 1857, and few bothered to attend. Delegates agreed to abandon the national campaign and return to local reforms, such as state-mandated waiting periods for immigrants before allowing them to vote. In 1858, Republicans, now boosted by Know Nothing converts, won control of Congress, and, in 1860, the presidency.

Though the Republican Party did not adopt any of the Know Nothing nativism when they absorbed their members, Republicans certainly benefitted from their votes and support. Republican Abraham Lincoln is the perfect example: Though he was an outspoken critic of nativists, he won their votes. “I am not a Know Nothing,” he stated emphatically in 1855. “How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor or degrading classes of white people? . . . As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.’ When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty.”

In the end, the Know Nothings were a partisan flash in the pan, but they made nativism a political strategy. Nativism flared again in the late 19th century as the nation experienced another spike in immigration, this time from China, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Today, the fight continues over people from Latin America and believers in Islam. The Know Nothings may be a fascinating phenomenon of the 1850s, but the way they used immigrants as political targets has persisted.

Michael Todd Landis is an assistant professor of history at Tarleton State University, a member of the Texas A&M University System. He is the author of Northern Men With Southern Loyalties: The Democratic Party and the Sectional Crisis (Cornell University Press, 2014).

Primary Editor: Reed Johnson | Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli

Add a Comment