On a sunny Saturday in August, I stood at a one-room cabin near the outskirts of Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, thinking about the great American poet Lorine Niedecker. She lived from 1903 to 1970, including many years in this tiny home, which stands on the bank of Rock River as it leads to Lake Koshkonong. She wrote some of the most beautiful American poems of the last century in and about this part of the world. I’ve read and taught and written about them. Yet I hadn’t much thought about the particular spot in which they were made. I made the trip to pay homage, not to change my interpretation of Niedecker’s poetry—or Niedecker’s place in American literature. And then, there on the riverbank, I did.

Niedecker’s verse is spare but rich. (She called her craft a “condensery,” as if it belonged in one of the dairies of her native state.) A Niedecker poem often moves in brief unpunctuated lines that savor words as sounds and things in themselves: “birdstart / wingdrip / weed-drift.” She makes the world mysterious but personable: She writes about “my friend tree” and “our relative the air,” and she knows how “stillness steps.” She cherished a “river-marsh-drowse.” She describes herself as a “solitary plover” with “a pencil / for a wing-bone.” But she also writes about “a country’s economics” and women’s choices. I had always preferred to describe Niedecker as a progressive feminist, not a nature poet or a Wisconsin writer. Looking at her cabin amid the trees and water, though—I realized my mistake. Niedecker’s poems about place and nature are a part of her political and economic concerns. In her work, American settings reveal the importance of a spiritual and material poverty. And it’s a connection that echoes throughout American literature.

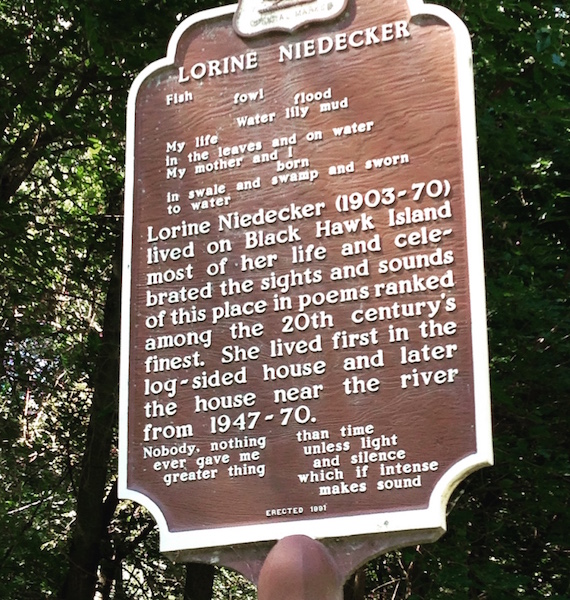

I felt the echoes partly because of comparisons that sprang to mind of a different humble cabin near a different inland body of water. Henry David Thoreau’s encounter with nature at Walden Pond still sets the standard for ecological engagement in American literature; Niedecker revises that engagement 1,000 miles west and a century later. There are obvious differences. Thoreau’s choice to go to the woods was solitary and “deliberate”; Niedecker’s residence at Blackhawk Island seems hardly a choice at all. She was born here and never left—not for long, anyway. There were two years of college at Beloit, a brief early marriage that brought her to town, some trips to New York, a job in Madison, a second, late marriage that kept her in Milwaukee for a while. (Margot Peters’ biography provides details.) Niedecker always came back. The river pulls at her with “Water lily mud / My life // in the leaves and on water.” She watches the flood rise; she endures as “water endows us / with buckled floors.” Thoreau would “front” the “essential facts” of nature, but Niedecker stood in the middle of them. She wrote from there. “O my floating life …,” she calls.

It wasn’t an easy one. Thoreau preached simplicity. He hoed beans. Niedecker lacked plumbing, until late in her career; she ate meals of cheap cereal. The difference between them, again, seems one of deliberation: Niedecker knew poverty as a condition rather than a decision. For most of her life she was economically insecure, working unsatisfactory posts as a proofreader or library assistant. In her 50s, she got up at five in the morning to walk to her job as a cleaning woman. Her verse describes the strain of such efforts—in her own life and in the lives of others. Her first book of poems, New Goose (1946), creates modern folktales, in poetry, of hardship and endurance. In the poem “Depression Years,” the speaker wonders if his daughters should support him, but “they’re not out of debt / from the last time they did.” Niedecker refused to romanticize impoverished lives; destitution was not a noble choice—nor was it always an individual one.

If Niedecker’s poverty and immersion in nature seem more circumstantial than Thoreau’s, that partly bespeaks her different situation as a woman, a wife, a daughter. But she used that situation; she found a method and a philosophy in where and how she lived. She read widely in both natural history and economics. And she thought deeply about the economics of the natural world. The results question a particularly American preoccupation with ownership, one arising in part from John Locke’s idea of life, liberty, and property as natural rights. For Niedecker, property brings constraint rather than liberty, and opens us to loss rather than more living. (“Property is poverty,” she wrote succinctly.) The extent of our claims, in Niedecker’s reckoning, is a measure of our vulnerability. She had to learn this lesson: when Niedecker first settled in a “house of her own,” in 1946, she hoped settlement might make her more “free.” By the time she wrote the great poem “Paean to Place,” though, in 1968, when she was in her 60s, she was telling herself to “throw things to the flood,” to “leave the new unbought.” The answer to poverty in Niedecker’s nature writing is not more ownership but less. Niedecker’s work can be a paean to place because it is a paean to letting things go.

Thoreau learned a similar lesson out at Walden Pond. Like Niedecker, he was conflicted about human holdings; like Niedecker, he looked to his natural surroundings to discover something different. As Stanley Cavell showed in his study of Thoreau, The Senses of Walden, the connection between nature and economics lies at the heart of Thoreau’s work. His prose, like Niedecker’s poetry, is full of financial vocabulary. And although he opens Walden by wondering why more men don’t own their homes “free and clear,” Thoreau’s work goes on to prove “the mysteriousness of ownership,” as Cavell put it—and the difficulties of seeking freedom through property.

Niedecker’s work lets us see these difficulties as part of a recurring theme in American nature writing—and not just from the 19th to the 20th century, but also into the 21st. When Jorie Graham writes her ecological “Prayer,” for example, another flowing-water poem, she has to let go of “what I have saved.” The “what” here seems abstract, immaterial. But it’s another species of property, another holding that nature teaches us to hold onto by relinquishing. Niedecker’s place in the American canon, and her place by the shores of a Wisconsin lake, underline this subtle lesson. All of our lives are, as she once wrote of her own, a “life by water.” The flood is coming.

writes poems and nonfiction. She teaches at Dickinson College and is an editor-at-large for Zócalo Public Square.

Primary editor: Sarah Rothbard. Secondary editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

*Lead photo courtesy of Siobhan Phillips. Interior photos courtesy of Siobhan Phillips and Lorine Niedecker collection, Hoard Historical Museum, Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin.

Add a Comment