For the Female Phone Operators of World War I, a Woman’s Place Was on the Front Lines

By Making the World Safe for Democracy, the "Hello Girls" Boosted Suffrage Back Home

L-R: Berthe Hunt, Esther “Tootsie” Fresnel, and Grace Banker run Gen. John Pershing’s switchboard at First Army headquarters. Note the helmets and gas masks hanging from their chairs. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

In 1917, U.S. Secretary of War Newton Baker disliked the idea of female workers on Army bases so intensely that he didn’t even want to build toilets for them. They might tarry. Females did not belong in the Army, Baker thought, though the more forward-thinking U.S. Navy already had welcomed women into its ranks to replace men in landlubber assignments.

Many adventurous and patriotic young women longed to defend their country during the Great War. They discovered that if they wanted to serve in uniform, they could not merely perform as well as the young men in the American Expeditionary Forces, who sailed to Europe in 1917 to help the Allies defeat the Germans. Women, still denied the vote, would have to perform better. They would have to do something the men could not. America’s ongoing Industrial Revolution gave the “Hello Girls,” as the first female recruits came to be known, their opportunity to serve the nation and earn full rights as citizens.

In May 1917, the month after Congress declared war on Germany, General John Pershing sailed for France. He stuffed his ship’s hold with the newest technologies: Military tackle had undergone a revolution since Pershing served in the Indian wars of the 1880s. Planes had replaced horses. Trucks had overtaken mule trains. Telephone wires had outrun flares and semaphore flags.

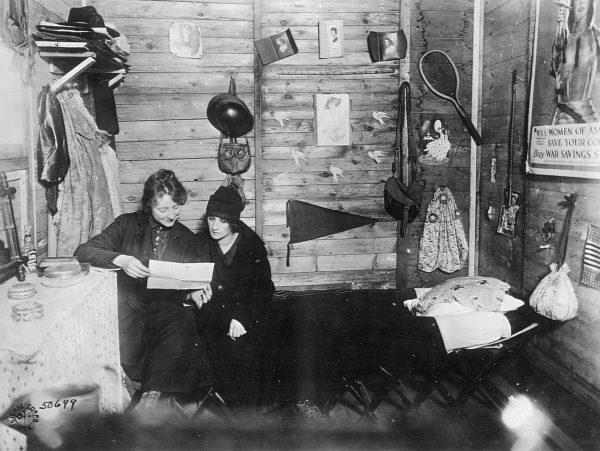

Sitting near a war bonds poster depicting Joan of Arc, Raymonde Breton (R) visits her sister Louise in the Signal Corps barracks at Neufchateau, later bombed by German planes. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Invented in the United States, American telephones reached farther, conveyed more messages on a wire, and reproduced sound with greater fidelity than telephones anywhere else in the world. They were the only military technology in which America enjoyed superiority over both allies and enemies. When the British commanding officer in World War I used an American-built line to place a call from France to England, he exclaimed, “Would you believe it? They actually recognized my voice in London before I told them who I was!”

Commands to advance or retreat, and to fire or stand down, were relayed by phone during the Great War. If America was going to position its immense armies quickly and effectively, it needed experts to handle this critical technology. “The importance of intercommunication in warfare cannot well be exaggerated,” wrote Brigadier General George Squier, chief signal officer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Without communications for even an hour, “the whole military machine would collapse.”

At home, telephone operating was sex-segregated. Callers rang female operators, who connected nearly every call made. Their job was demanding. With hands darting like hummingbirds, operators connected hundreds of impatient callers each hour. Diligent and quick, they talked with customers while manipulating plugs in a constantly changing pattern.

U.S. General John “Black Jack” Pershing inspects switchboard operators serving in occupied Germany. Women remained on duty until discharged after World War I ended in November 1918. The last women were relieved in 1920. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

When Pershing arrived in France, he found male recruits ill-suited for this work. They were inefficient, and prone to frustration when dealing with rude callers. Few doughboys possessed the foreign language skills necessary to cooperate with French telephone operators when making long-distance connections. Necessity required innovation, so Pershing—an innovative thinker who had been nicknamed “Black Jack” after he commanded an African-American regiment on the frontier—departed from precedent, law, and the wishes of the Army itself to recruit women. Before most doughboys arrived, and well after they left, bilingual women served in France. They withstood submarine warfare, cannon fire, influenza, aerial bombardment, and petty-minded bureaucrats to send the word, over there.

Most worked behind the lines in safer regions of France. But one small group, led by Grace Banker, a 25-year-old graduate of Barnard College, followed Pershing from the short but intense Battle of St. Mihiel to the desperately extended Meuse-Argonne Offensive, lasting 47 days. The women ran switchboards 24 hours a day within range of artillery fire that lit up the horizon and shook their equipment. Enemy planes buzzed overhead. A German prisoner of war overturned an oil stove and burned their barracks to the ground. Yet the indomitable women embraced every challenge. The highest aspiration of nearly every female Signal Corps member was to serve as near the battle as possible.

Grace Banker, with three service stripes on her sleeve, wears the Distinguished Service Medal, awarded to only 18 Signal Corps officers of the U.S. Army, including her. Photo courtesy of Robert, Grace, and Carolyn Timbie.

Their efforts, along with those of female Army nurses and private volunteers, helped shape another great debate: whether or not to grant women the vote. World War I altered expectations about citizenship globally. Not only did the Russian, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and German Empires fragment into a dozen new nations, but cracks also ran under the British, French, and Dutch Empires as diverse peoples claimed a right to popular sovereignty. Within older democracies, groups who never had much voice raised theirs with new conviction.

Women, in particular, leveraged the conflict for suffrage. By war’s end, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Great Britain, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and 10 other countries had enfranchised females. Not surprisingly, the nation latest to the war was also late to the vote. Accustomed to congratulating itself as the vanguard of democracy, the United States brought up the rear. Its suffrage movement had struggled for 70 years without producing victory. Founders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton died without seeing their life’s work fulfilled.

But the war—and female recruits’ efforts in battle—changed the mind of one crucial U.S. leader: President Woodrow Wilson. Prior to his election in 1912, he told an aide that he was “definitely and irreconcilably opposed to woman suffrage; woman’s place was in the home, and the type of woman who took an active part in the suffrage agitation was totally abhorrent to him.”

Six years later, at the height of American fighting in France, Wilson told the U.S. Senate that the women’s vote was vital to the “realization of the objects for which the war is being fought.” He hoped America might eventually organize an enduring democratic peace, guaranteed by a League of Nations. But how could the United States lead the free world if it was behind everyone else? Once women’s suffrage was entangled with Wilson’s foreign policy goals, it became necessary, not discretionary. The president made two arguments: The United States could not hold itself aloof from world opinion, and women had amply earned the privileges of citizenship.

General Pershing Entering St. Mihiel by Ernest Clifford Peixotto, 1918. Image courtesy of Division of Armed Forces History, National Museum of American History.

“Are we alone to refuse to learn the lesson?” he asked the conservative Senate. Wilson made scant reference to suffragists in his speeches to Congress. Militant activists continued to irk him. But he had come to admire female citizens doing their duty “upon the very skirts and edges of the battle itself.” The war could not be fought without them. “Are we alone to ask and take the utmost women can give—service and sacrifice of every kind—and still say that we do not see what title that gives them?” the president asked. “Shall we admit them only to a partnership of sacrifice and suffering and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and of right?”

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, Grace Banker received the Distinguished Service Medal for assuring “the success of the telephone service during the operations of the First Army against the St. Mihiel salient and the operations to the north of Verdun.” Only 18 out of 16,000 eligible Signal Corps officers received the medal. Grace Banker was one of them. Thirty other women received citations for “exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous services” in the war zone.

U.S. Army Signal Corps Female Telephone Operator uniform. Worn by Helen Cook, Chief Operator. Gift of Helen Cook through The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America. Image courtesy of Division of Armed Forces History, National Museum of American History. On view in Uniformed Women in the Great War.

Sadly, such recognition was transitory. Once operators returned home in 1919 (two died in France), the Army denied them veterans’ bonuses, victory medals, hospitalization for disabilities, and even a flag on their coffins. As a result, the Hello Girls commenced a new struggle for recognition as veterans that eventually caught the second wave of feminism. In 1979, assisted by the National Organization for Women, 31 survivors received their World War I Victory Medals at last.

Yet every Hello Girl had the satisfaction of knowing she had demonstrated women’s willingness to fulfill the hardest duty of citizenship. As testimony in the Congressional Record for 1918 and 1919 shows, the men who helped pass the Susan B. Anthony Amendment—which finally gave women the right to vote—understood this, too.

“Women have performed more than their part in this great struggle for democracy, freedom, and liberty,” Senator William Thompson said, echoing many others. In the United States, France, and England, female citizens had produced food, guns, ammunition, planes, and trains. They loaded baggage, drove trucks, operated switchboards, and were ready, “if necessary, to shoulder the gun and march to the front themselves.” Thompson had traveled throughout the war zone. Women, he found, were praised everywhere.

Women’s activism laid the basis for women’s suffrage. World War I secured it. The Hello Girls fought on both fronts.

Author of The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers, Elizabeth Cobbs holds the Melbern Glasscock Chair at Texas A&M and is a Research Fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. She is the author of seven books, and a winner of the Allan Nevins Prize, Bernath Book Prize, and San Diego Book Award. She has written for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Jerusalem Post, and Reuters.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment