How the South Recast Defeat as Victory with an Army of Stone Soldiers

Confederate Monuments to Nameless Infantrymen Were Less About Celebrating History Than Reestablishing Social Order

In Monticello, Georgia, a 1910 stone obelisk is flanked by statues of two Confederate soldiers: an officer with a saber (left), and a young private holding a rifle. Photo by Gregory Rodriguez.

Monuments to Robert E. Lee and other Confederate leaders have long been controversial, but monuments to nameless Confederate soldiers, those lone stone figures in public places, are far more common and have long served as an iconic symbol of the South. Understanding the origins of these stone soldiers who still loom over present-day towns and cities may help us better understand current controversies over them.

The white South began to erect soldiers’ monuments soon after the Confederacy’s defeat. In the first two decades after the war, communities most often chose a simple obelisk or other monument of funeral design and placed it in a cemetery. Former Confederates thereby mourned their dead and memorialized their cause. Even in the early years after the war, though, some monuments featured a sculpture of a soldier and occupied a more public place—a practice that increased over the next two decades.

The vast majority of Confederate monuments were erected between 1890 and 1912, and most of these consisted of a single soldier, with his hands folded over the top of his rifle’s barrel and with its stock resting on the ground. Typically, the soldier stood atop a column on the courthouse lawn or some other central public space. These statues hardly seemed martial, much less ready to attack. Indeed, they looked surprisingly calm and at ease. They did not always face north, as folklore has it but, rather, whichever way the courthouse faced.

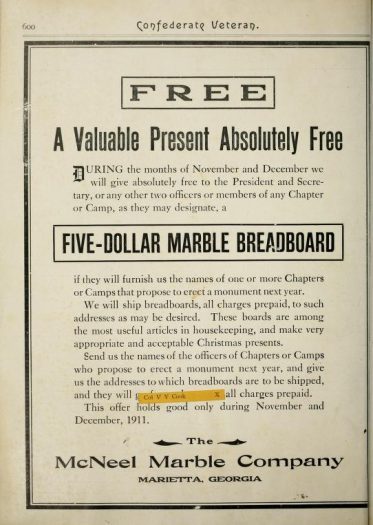

An advertisement for soldier monuments in the magazine, Confederate Veteran. Image courtesy of Gaines Foster.

The origins and purposes of these monuments to the common Confederate soldier is complex. They resulted, in part, from a commercial campaign. Monument companies advertised in veterans’ magazines and hired agents to travel the South. They offered credit terms (lest the veterans die before a town could raise the money for a memorial) and, in one ad, even offered a free marble breadboard to the secretary of any United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter that ordered a monument.

The companies, though, were exploiting an important cultural movement. Putting up soldiers’ monuments was a central ritual of the Lost Cause, a shorthand term for an organized attempt by the Daughters, Confederate veterans, and many other white Southerners to shape the memory of the Civil War. Southern whites erected Confederate soldier monuments for at least three interrelated reasons.

The leaders of the Lost Cause first sought to honor the veterans of the war. The monuments expressed white society’s appreciation and respect for the soldiers’ wartime sacrifice, constituting a more profound and permanent version of today’s off-hand “thank you for your service.” The monuments also reassured the veterans that, despite losing on the battlefield, they had fought honorably and well—and for the noblest of reasons.

The Lost Cause and the monuments that emerged from it also sought to vindicate the Confederacy itself. The white South’s memory of the war claimed that soldiers fought for states’ rights and the defense of their homes and families. The Lost Cause also proclaimed secession to be legal, denied the centrality of slavery to the war, ignored the evil inherent in the South’s peculiar institution, and over time romanticized it. The monuments thereby celebrate not just the veterans but the Confederacy and, despite the attempt to deny it, its cause—slavery.

The Lost Cause thereby offered a vision of the “proper” social order, one in which the lower classes deferred to leaders, women proved loyal to men, and African Americans remained subservient to whites.

Finally, although they celebrated the Confederacy, the monuments and the Lost Cause were as much about the present as the past. In honoring the faithful soldier, the Lost Cause’s leaders made him a model for the lower classes in a turbulent period of change in the South and the nation.

The erection of the monuments followed the populist revolt and widespread labor unrest. The soldier statues were a reminder that, as during the war—when Confederate soldiers loyally followed aristocratic leaders like Lee into battle—the middle and lower classes should be loyal to a hierarchical society. The Lost Cause thereby offered a vision of the “proper” social order, one in which the lower classes deferred to leaders, women proved loyal to men, and African Americans remained subservient to whites. In the same decades in which most of the soldiers’ monuments went up, the white South created a repressive racial order based on segregation, disfranchisement, lynching, and other forms of white racial violence.

The story of the Lost Cause’s monuments to the Confederate soldier reveals the difficulty of knowing how to honor soldiers’ sacrifices without embracing or even justifying their cause—a problem also faced by later generations of Americans struggling over some subsequent wars. It shows that monuments emerge more from memory—an attempt to shape the past—than from the history that actually happened. And, in the midst of a public debate over Confederate monuments, it reminds us that memory and its symbols have less to say about history and more to proclaim about the shape of society in the present and the future.

Gaines M. Foster is professor of history at Louisiana State University and author of Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1912.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment