When Halloween Mischief Turned to Mayhem

Nineteenth-Century Urbanization Unleashed the Nation's Anarchic Spirits

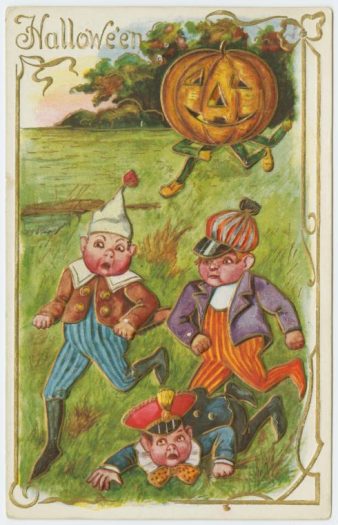

A 1908 postcard depicts Halloween mischief. Image courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Imagine. Pre-electricity, no moon. It’s late October, and the people whisper: This is the season for witchery, the night the spirits of the dead rise from their graves and hover behind the hedges.

The wind kicks up, and branches click like skeletal finger bones. You make it home, run inside, wedge a chair against the door, and strain to listen. There’s a sharp rap at the window and when you turn, terrified, it’s there leering at you—a glowing, disembodied head with a deep black hole where its mouth should be.

It’s just a scooped-out pumpkin, nicked from a field by some local boys and lit from the inside with the stub of a candle. But it has spooked you. When you look again, it’s gone.

Halloween in early 19th-century America was a night for pranks, tricks, illusions, and anarchy. Jack-o’-lanterns dangled from the ends of sticks, and teens jumped out from behind walls to terrorize smaller kids. Like the pumpkin patches and pageants that kids love today, it was all in good fun—but then, over time, it wasn’t.

As America modernized and urbanized, mischief turned to mayhem and eventually incited a movement to quell what the mid-20th-century press called the “Halloween problem”—and to make the holiday a safer diversion for youngsters. If it weren’t for the tricks of the past, there’d be no treats today.

Halloween was born nearly 2,000 years ago in the Celtic countries of northwestern Europe. November 1 was the right time for it—the date cut the agricultural year in two. It was Samhain, summer’s end, the beginning of the dangerous season of darkness and cold—which according to folklore, created a rift in reality that set spirits free, both good and bad. Those spirits were to blame for the creepy things—people lost in fairy mounds, dangerous creatures that emerged from the mist—that happened at that time of year.

Immigrants from Ireland and Scotland brought their Halloween superstitions to America in the 18th and 19th centuries, and their youngsters—our great- and great-great grandfathers—became the first American masterminds of mischief. Kids strung ropes across sidewalks to trip people in the dark, tied the doorknobs of opposing apartments together, mowed down shrubs, upset swill barrels, rattled or soaped windows, and, once, filled the streets of Catalina Island with boats. Pranksters coated chapel seats with molasses in 1887, exploded pipe bombs for kicks in 1888, and smeared the walls of new houses with black paint in 1891. Two hundred boys in Washington, D.C., used bags of flour to attack well-dressed folks on streetcars in 1894.

Teens used to terrorize smaller children on Halloween. Image courtesy of The New York Public Library.

In this era, when Americans generally lived in small communities and better knew their neighbors, it was often the local grouch who was the brunt of Halloween mischief. The children would cause trouble and the adults would just smile guiltily to themselves, amused by rocking chairs engineered onto rooftops, or pigs set free from sties. But when early 20th-century Americans moved into crowded urban centers—full of big city problems like poverty, segregation, and unemployment—pranking took on a new edge. Kids pulled fire alarms, threw bricks through shop windows, and painted obscenities on the principal’s home. They struck out blindly against property owners, adults, and authority in general. They begged for money or sweets, and threatened vandalism if they didn’t receive them.

Some grown-ups began to fight back. Newspapers in the early 20th century reported incidents of homeowners firing buckshot at pranksters who were only 11 or 12 years old. “Letting the air out of tires isn’t fun anymore,” wrote the Superintendent of Schools of Rochester, New York in a newspaper editorial in 1942, as U.S. participation in World War II was escalating. “It’s sabotage. Soaping windows isn’t fun this year. Your government needs soaps and greases for the war … Even ringing doorbells has lost its appeal because it may mean disturbing the sleep of a tired war worker who needs his rest.” That same year, the Chicago City Council voted to abolish Halloween and instead institute a “Conservation Day” on October 31. (Implementation got kicked to the mayor, who doesn’t appear to have done much about it.)

The effort to restrain and recast the holiday continued after World War II, as adults moved Halloween celebrations indoors and away from destructive tricks, and gave the holiday over to younger and younger children. The Senate Judiciary Committee under President Truman recommended Halloween be repurposed as “Youth Honor Day” in 1950, hoping that communities would celebrate and cultivate the moral fiber of children. The House of Representatives, sidetracked by the Korean War, neglected to act on the motion, but there were communities that took it up: On October 31, 1955 in Ocala, Florida, a Youth Honor Day king and queen were crowned at a massive party sponsored by the local Moose Lodge. As late as 1962, New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. wanted to change Halloween to UNICEF Day, to shift the emphasis of the night to charity.

Of course, the real solution was already gaining in practice by that time. Since there were children already out demanding sweets or money, why not turn it into it a constructive tradition? Teach them how to politely ask for sweets from neighbors, and urge adults to have treats at the ready. The first magazine articles detailing “trick or treat” in the United States appeared in The American Home in the late 1930s. Radio programs aimed at children, such as The Baby Snooks Show, and TV shows aimed at families, like The Jack Benny Program, put the idea of trick-or-treating in front of a national audience. The 1952 Donald Duck cartoon Trick or Treat reached millions via movie screens and TV. It featured the antics of Huey, Dewey, and Louie, who, with the help of Witch Hazel’s potions, get Uncle Donald to give them candy instead of the explosives he first pops into their treat bags.

When early 20th-century Americans moved into crowded urban centers […], pranking took on a new edge. Kids pulled fire alarms, threw bricks through shop windows, and painted obscenities on the principal’s home.

The transition could be slow. On one episode of The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, costumed kids come to the door, and Ozzie and Harriet are baffled. But food companies—Beatrice Foods, Borden, National Biscuit Company—quickly took notice and got into the candy business, and even tobacco companies like Philip Morris jumped in. Halloween candy and costume profits hit $300 million in 1965 and kept rising. Trick-or-treating—child-oriented and ideal for the emerging suburbs that housed a generation of Baby Boomers—became synonymous with Halloween. Reckless behavior was muted, and porch lights welcomed costumed kids coast to coast.

Today, trick or treat has more variants: trunk or treat, where kids go car-to-car in a parking lot asking for candy; and trick or treat for UNICEF, where youngsters collect money for charity along with their treats. Few children, especially young ones, have an inkling of what mischief was once possible.

For those nostalgic about the old days of Halloween mischief, all is not lost. Query the MIT police about the dissected-and-reassembled police car placed atop the Great Dome on the college’s Cambridge campus in 1994. Or ask the New York City pranksters who decorated a Lexington Avenue subway car as a haunted house in 2008. There’s even an annual Naked Pumpkin Run in Boulder, Colorado.

The modern Halloween prank—be it spectacle, internet joke, entertainment, or clever subversion—is a treat in disguise, an offering that’s usually as much fun for the tricked as it is for the trickster. Halloween is still seen as a day to cause mischief, to mock authority, and make the haves give to the have-nots—or at least shine a light on the fact that they should. For that, Americans can thank the long line of pranksters who came before us.

Lesley Bannatyne has written extensively on Halloween. Her latest book, Halloween Nation, was nominated for a 2011 Bram Stoker Award; Halloween: An American Holiday, An American History celebrated 25 years in print in 2015. In 2007, Bannatyne and collaborators set the Guinness World Record for largest Halloween gathering, a title they held until 2009.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Joe Mathews.

Add a Comment