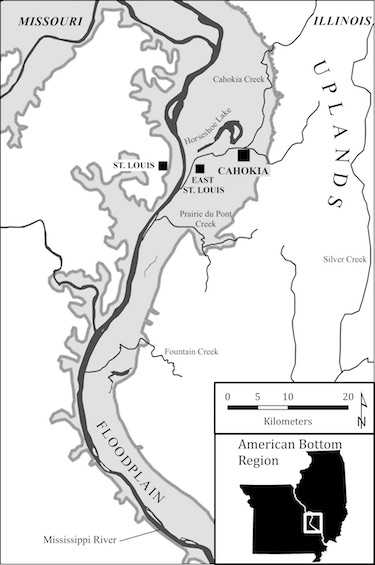

Around 1100 or 1200 A.D., the largest city north of Mexico was Cahokia, sitting in what is now southern Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. Built around 1050 A.D. and occupied through 1400 A.D., Cahokia had a peak population of between 25,000 and 50,000 people. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Cahokia was composed of three boroughs (Cahokia, East St. Louis, and St. Louis) connected to each other via waterways and walking trails that extended across the Mississippi River floodplain for some 20 square km. Its population consisted of agriculturalists who grew large amounts of maize, and craft specialists who made beautiful pots, shell jewelry, arrow-points, and flint clay figurines.

The city of Cahokia is one of many large earthen mound complexes that dot the landscapes of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and across the Southeast. Despite the preponderance of archaeological evidence that these mound complexes were the work of sophisticated Native American civilizations, this rich history was obscured by the Myth of the Mound Builders, a narrative that arose ostensibly to explain the existence of the mounds. Examining both the history of Cahokia and the historic myths that were created to explain it reveals the troubling role that early archaeologists played in diminishing, or even eradicating, the achievements of pre-Columbian civilizations on the North American continent, just as the U.S. government was expanding westward by taking control of Native American lands.

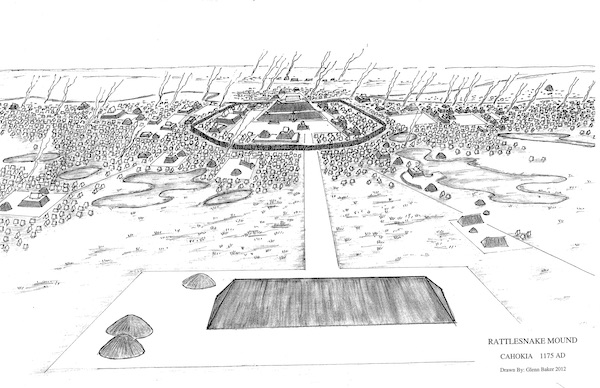

Today it’s difficult to grasp the size and complexity of Cahokia, composed of about 190 mounds in platform, ridge-top, and circular shapes aligned to a planned city grid oriented five degrees east of north. This alignment, according to Tim Pauketat, professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois, is tied to the summer solstice sunrise and the southern maximum moonrise, orientating Cahokia to the movement of both the sun and the moon. Neighborhood houses, causeways, plazas, and mounds were intentionally aligned to this city grid. Imagine yourself walking out from Cahokia’s downtown; on your journey you would encounter neighborhoods of rectangular, semi-subterranean houses, central hearth fires, storage pits, and smaller community plazas interspersed with ritual and public buildings. We know Cahokia’s population was diverse, with people moving to this city from across the midcontinent, likely speaking different dialects and bringing with them some of their old ways of life.

View of Cahokia from Rattlesnake Mound ca 1175 A.D., drawn by Glen Baker. Image courtesy of Sarah E. Baires.

The largest mound at Cahokia was Monks Mound, a four-terraced platform mound about 100 feet high that served as the city’s central point. Atop its summit sat one of the largest rectangular buildings ever constructed at Cahokia; it likely served as a ritual space.

In front of Monks Mound was a large, open plaza that held a chunk yard to play the popular sport of chunkey. This game, watched by thousands of spectators, was played by two large groups who would run across the plaza lobbing spears at a rolling stone disk. The goal of the game was to land their spear at the point where the disk would stop rolling. In addition to the chunk yard, upright marker posts and additional platform mounds were situated along the plaza edges. Ridge-top burial mounds were placed along Cahokia’s central organizing grid, marked by the Rattlesnake Causeway, and along the city limits.

Cahokia was built rapidly, with thousands of people coming together to participate in its construction. As far as archaeologists know, there was no forced labor used to build these mounds; instead, people came together for big feasts and gatherings that celebrated the construction of the mounds.

The splendor of the mounds was visible to the first white people who described them. But they thought that the American Indian known to early white settlers could not have built any of the great earthworks that dotted the midcontinent. So the question then became: Who built the mounds?

Early archaeologists working to answer the question of who built the mounds attributed them to the Toltecs, Vikings, Welshmen, Hindus, and many others. It seemed that any group—other than the American Indian—could serve as the likely architects of the great earthworks. The impact of this narrative led to some of early America’s most rigorous archaeology, as the quest to determine where these mounds came from became salacious conversation pieces for America’s middle and upper classes. The Ohio earthworks, such as Newark Earthworks, a National Historic Landmark located just outside Newark, OH, for example, were thought by John Fitch (builder of America’s first steam-powered boat in 1785) to be military-style fortifications. This contributed to the notion that, prior to the Native American, highly skilled warriors of unknown origin had populated the North American continent.

This was particularly salient in the Midwest and Southeast, where earthen mounds from the Archaic, Hopewell, and Mississippian time periods crisscross the midcontinent. These landscapes and the mounds built upon them quickly became places of fantasy, where speculation as to their origins rose from the grassy prairies and vast floodplains, just like the mounds themselves. According to Gordon Sayre (The Mound Builders and the Imagination of American Antiquity in Jefferson, Bartram, and Chateaubriand), the tales of the origins of the mounds were often based in a “fascination with antiquity and architecture,” as “ruins of a distant past,” or as “natural” manifestations of the landscape.

When William Bartram and others recorded local Native American narratives of the mounds, they seemingly corroborated these mythical origins of the mounds. According to Bartram’s early journals (Travels, originally published in 1791) the Creek and the Cherokee who lived around mounds attributed their construction to “the ancients, many ages prior to their arrival and possessing of this country.” Bartram’s account of Creek and Cherokee histories led to the view that these Native Americans were colonizers, just like Euro-Americans. This served as one more way to justify the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands: If Native Americans were early colonizers, too, the logic went, then white Americans had just as much right to the land as indigenous peoples.

Location of Cahokia, East St Louis, and St Louis sites in the American Bottom. Map courtesy of Sarah E. Baires.

The creation of the Myth of the Mounds parallels early American expansionist practices like the state-sanctioned removal of Native peoples from their ancestral lands to make way for the movement of “new” Americans into the Western “frontier.” Part of this forced removal included the erasure of Native American ties to their cultural landscapes.

In the 19th century, evolutionary theory began to take hold of the interpretations of the past, as archaeological research moved away from the armchair and into the realm of scientific inquiry. Within this frame of reference, antiquarians and early archaeologists, as described by Bruce Trigger, attempted to demonstrate that the New World, like the Old World, “could boast indigenous cultural achievements rivaling those of Europe.” Discoveries of ancient stone cities in Central America and Mexico served as the catalyst for this quest, recognizing New World societies as comparable culturally and technologically to those of Europe.

But this perspective collided with Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1881 text Houses and House-life of the American Aborigines. Morgan, an anthropologist and social theorist, argued that Mesoamerican societies (such as the Maya and Aztec) exemplified the evolutionary category of “Middle Barbarism”—the highest stage of cultural and technological evolution to be achieved by any indigenous group in the Americas. By contrast, Morgan said that Native Americans located in the growing territories of the new United States were quintessential examples of “Stone Age” cultures—unprogressive and static communities incapable of technological or cultural advancement. These ideologies framed the archaeological research of the time.

In juxtaposition to this evolutionary model there was unease about the “Vanishing Indian,” a myth-history of the 18th and 19th centuries that depicted Native Americans as a vanishing race incapable of adapting to the new American civilization. The sentimentalized ideal of the Vanishing Indian—who were seen as noble but ultimately doomed to be vanquished by a superior white civilization—held that these “vanishing” people, their customs, beliefs, and practices, must be documented for posterity. Thomas Jefferson was one of the first to excavate into a Native American burial mound, citing the disappearance of the “noble” Indians—caused by violence and the corruption of the encroaching white civilization—as the need for these excavations. Enlightenment-inspired scholars and some of America’s Founders viewed Indians as the first Americans, to be used as models by the new republic in the creation of its own legacy and national identity.

During the last 100 years, extensive archaeological research has changed our understanding of the mounds. They are no longer viewed as isolated monuments created by a mysterious race. Instead, the mounds of North America have been proven to be constructions by Native American peoples for a variety of purposes. Today, some tribes, like the Mississippi Band of Choctaw, view these mounds as central places tying their communities to their ancestral lands. Similar to other ancient cities throughout the world, Native North Americans venerate their ties to history through the places they built.

Sarah E. Baires is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Eastern Connecticut State University. She is the author of Land of Water, City of Dead: Religion and Cahokia’s Emergence, which examines the role of mortuary practice and religious belief in creating the City of Cahokia.

Primary Editor: Reed Johnson | Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli.

Add a Comment