For his brief reign atop the Gambino crime family, in the late 1980s, John Gotti, the “Teflon Don,” was the heir apparent to Al Capone as America’s top mob boss. Gotti was as extravagant as he was charismatic, with a larger-than-life persona that extended to his taste for the finer things, including drink. As gifts, he liked to give his loyal underlings bottles of Rémy Martin Louis XIII Cognac, which can run in the thousands.

After Gotti was sentenced to life in prison in 1992, the FBI did their best to trace all the money funneled through the Gambino crime family. There was far less than they thought. As FBI field office head James Fox put it, “Gotti and the others spent a lot on drinking, gambling, and girlfriends.” Much of that, no doubt, went to bottles of Louis XIII.

The tie between booze and gangsters has been around since the early 1900s, when mobsters started using dark and dingy bars to plot their crimes and hang out with fellow underworld denizens. But it was Prohibition that really cemented the relationship. In the 1920s, gangsters became the main suppliers of illicit booze—whiskey and scotch from Canada and Europe, rum from Cuba, and homemade moonshine form rural operations across the country. Prohibition gave the underworld the financial clout to extend their influence into politics and coalesce a national criminal syndicate.

Post-Prohibition, many mobsters who made their fortune with bootleg liquor plied their ill-gotten funds into liquor distributorships, stores, breweries, and state beverage commissions to control liquor licenses. Most of all, they bought bars—lots of them. As former Gambino crime family associate John Alite said, “Wiseguys look for attention. A good mob bar is where they have a hook and know everybody.” Bars also served a useful cash-laundering purpose.

Among gangsters, scotch and whiskey were always popular choices, particularly the whiskey brand Cutty Sark. And they had their own way of ordering, as recounted by undercover FBI agent Jack Garcia: “Mobsters always order drinks by a brand. Never just a scotch and water, it would be a Cutty and water. And no one ever drank out of a straw. That was a big no-no. Mobsters would always get free drinks, but loved to tip extravagantly, so the drinks would end up costing more just because of their big tips. But for a wiseguy it didn’t matter. To them the best drink is the one you get for free.”

For all the time wiseguys spent in bars, and for the decades of their ties to the industry, it was inevitable that cocktails would bear their name. Here are four major gangsters in American history and the cocktails named after them.

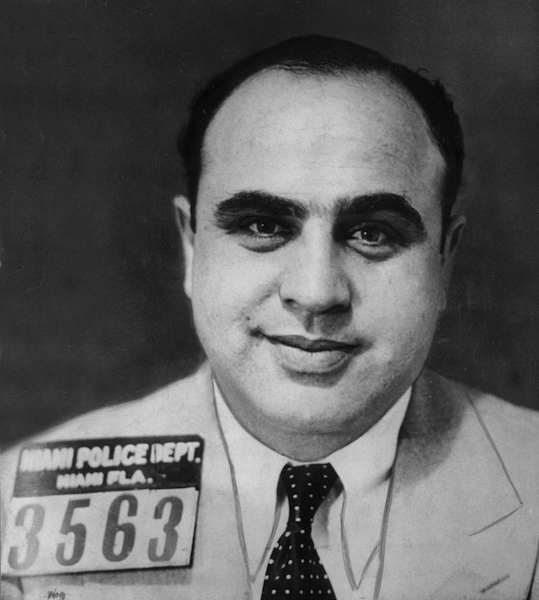

Al Capone, the most famous American gangster.

Al Capone

Few gangsters loom larger in American history, and pop culture, than Al Capone. Though he reigned over the Chicago underworld for only seven years, from 1925 to 1932, he managed to turn his swagger and media savvy into gangland celebrity, hobnobbing with politicians, judges, movie stars, singers, stage actors, and baseball players. During Prohibition, liquor made his empire and his fortune. It also made him the target of law enforcement and one of the first mob bosses to catch the attention of the federal government.

For his own consumption, Capone was reported to prefer Manhattans; whiskey was a popular bootleg alcohol in Chicagoland. He would have his drinks, and listen to the top jazz acts of the day at The Green Mill, a historic Chicago lounge. There’s a booth, facing the stage on the right hand side, that the bar’s staff call the Capone booth. Whenever he was there, no one could come in or leave the Mill.

The Al Capone Cocktail

Saveur magazine printed this recipe, from Brooklyn bartender John Bush. The Al Capone is a close cousin to the Boulevardier.

3 oz. rye whiskey

1½ oz. vermouth

½ oz. Campari

Orange zest, to garnishIn a cocktail shaker filled with ice, shake the whiskey, vermouth, and Campari. Strain the mixture into two tumblers, and garnish each with an orange twist.

Meyer Lansky

Despite his nickname, the “Little Man,” Meyer Lansky was a huge figure in organized crime history. A Jewish émigré from Poland, Lansky grew up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with little formal schooling. He quickly attached himself to gangs of Jewish and Italian racketeers, who were active in the underworld during Prohibition. Lansky started running gambling operations, and eventually owned casinos in pre-Castro Cuba and the Bahamas, as well as financial interests in Las Vegas casinos, like the Flamingo.

According to his daughter, Sandi Lansky, Meyer favored scotch, specifically Dewar’s. Scotch was a perennial favorite drink for many gangsters, and Dewar’s has long been one of the most popular whiskeys in the United States, especially during the post-World World II era.

Though Lanksy preferred his drinks straight, his name inspired a few modern cocktails, including this one found on the menu of the DGS Delicatessen, in Washington, D.C.

The Meyer Lansky Sour

2 oz. gin

1 ½ oz. Meyer lemon juice

1 dash orange bitters

Simple syrupPour all ingredients into a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake for 30 seconds. Strain into chilled glass.

Lucky Luciano

Lucky Luciano was the archetypical 1930s-era gangster. He’s often cited as one of the influential figures in the development of modern organized crime—not only for his criminal exploits, but for his style. Wearing sharp suits, Luciano was one of the architects of the Mafia Commission and led one of the NYC Mafia’s five families.

But he was noticeably different from his peers in one way. “Despite the fact he and his pals made millions off of Prohibition liquor, it seems Charlie was not a particularly ‘big’ drinker himself,” says author Christian Cipollini.

Lucky’s Manhattan

In 2011, Basil Hayden’s Bourbon worked with HBO to develop signature cocktails inspired by the show Boardwalk Empire.

1½ oz. Basil Hayden’s Bourbon

½ oz. sweet vermouth

½ oz. dry vermouth

½ oz. maple syrup

2 dashes of bittersStir together bourbon, sweet and dry vermouth, maple syrup, and bitters over ice in a glass. Garnish with a maraschino cherry.

Santo Trafficante, Jr.

The mob in Tampa was never as large as its counterparts in the Northeast and Midwest. But despite its small size, the Trafficantes, Florida’s only Mafia family, controlled a vast swath of the Sunshine State and extended its tentacles into pre-Castro Cuba, under the tutelage of Santo Trafficante, Jr. Unlike Capone or Gotti, Trafficante was quiet and unassuming. He ran the Tampa family for more than 30 years, owned and operated casinos in Havana, and was highly respected by Mafia bosses around the country.

The Santo Trafficante Cocktail

Though it doesn’t contain the Florida don’s favorite scotch, J&B, this cocktail from New York-based Prohibition Distillers has a Sunshine State feel to it because of its the layered orange flavors.

3 oz. orange-infused Bootlegger vodka

1 oz. blood orange puree

1 oz. fresh orange juice

Dash of CampariShake the ingredients in a shaker with ice until well blended. Strain into a chilled martini glass and garnish with an orange twist.

is the author of six books on organized crime, most recently Cocktail Noir: From Gangsters and Gin Joints to Gumshoes and Gimlets.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon.

Primary editor: Paul Bisceglio. Secondary editor: Andrés Martinez.

*Lead photo courtesy of Scott M. Deitche. Interior photos courtesy of Sari Deitche and Scott M. Deitche.

Add a Comment