For much of the 20th century, the Scurlock family of portrait photographers—first Addison Scurlock and his wife Mamie and then their sons Robert and George—were the premiere chroniclers of the aspirational lives of Washington D.C.’s black middle class. Over time they forged close working relationships with W.E.B. DuBois and Howard University, as well as photographing Marian Anderson, Duke Ellington, and Booker T. Washington.

But alongside this work—now preserved at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History as “Portraits of a City: The Scurlock Photographic Studio’s Legacy to Washington, D.C.”—are the family’s abundant but lesser-known images of schoolchildren.

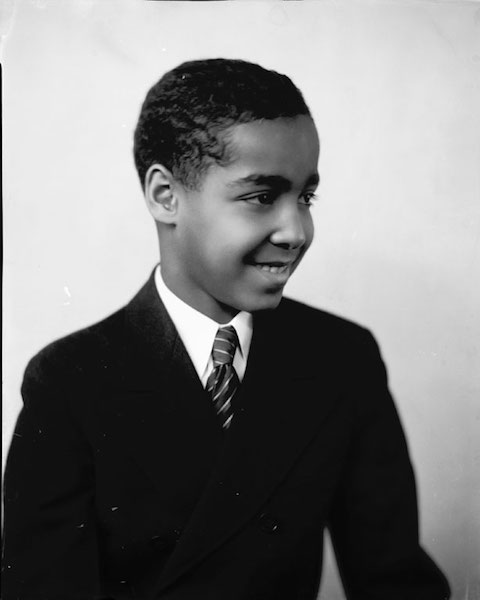

Charles Tignor Duncan, who went on to become dean of Howard University Law School and submit a brief in Brown v. Board of Education.

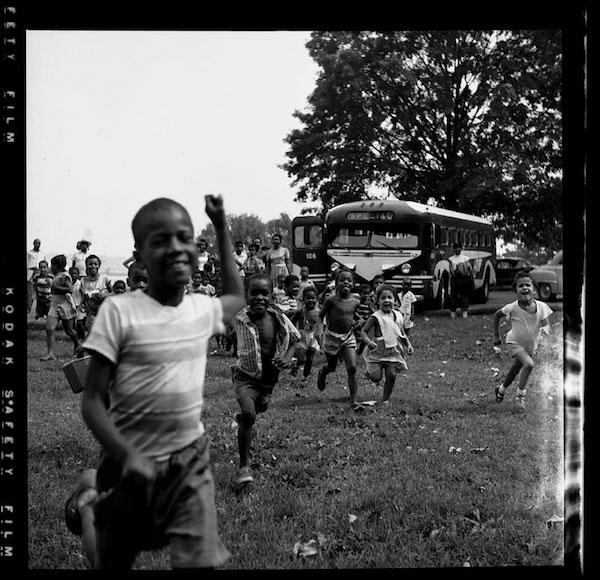

These are exquisitely posed demonstrations of the promise of the next generation, a generation—theoretically anyway—less burdened by and beholden to a heavy, harmful past. Children with more freedom, to think and learn and acquire a good education.

The Scurlocks endeavored to portray the subjects of all of their work in the most flattering light, dressed in Sunday finery or their Lindy Hop best. They showcased the best examples in the display window of their U Street studio. To make it into the window became a substantiation of success.

As author and journalist Wil Haygood put it: “The style of their work—refined, dignified and poised—became known as ‘the Scurlock look.’ It said a lot of things, chief among them that classiness is swell and uplift gets rewarded.”

To create and sustain this view took a deep commitment, one handed down from father to sons. In a 2003 interview, Robert Scurlock described his father as “very intense, in all of his endeavors.” And so for more than six decades the Scurlocks documented, collected, and shared an idealized beauty, and in that act declared that this, too, was a part of the story of black America worth knowing and telling.

This mission presented a particular challenge when it came to portraying the schoolchildren of Washington D.C., where the educational inequities that scourged the nation emerged in a particular way. Unlike anywhere else in the country, public school teachers were employees of the federal government, and so they were paid the same regardless of skin color. The District was also home to the nation’s first public high school for non-white students, named for Paul Laurence Dunbar, whose own literary career, as one of the first nationally recognized black poets, was launched during his years attending an all-white high school.

Sharon Jones’ birthday party at Mrs. Howard’s Nursery School, March 1949. More about this photo.

And yet, the ugliness of segregation and the hardships that it wrought persisted—a school desegregation case from Washington D.C. was one of five from around the country that were combined into Brown v. Board of Education.

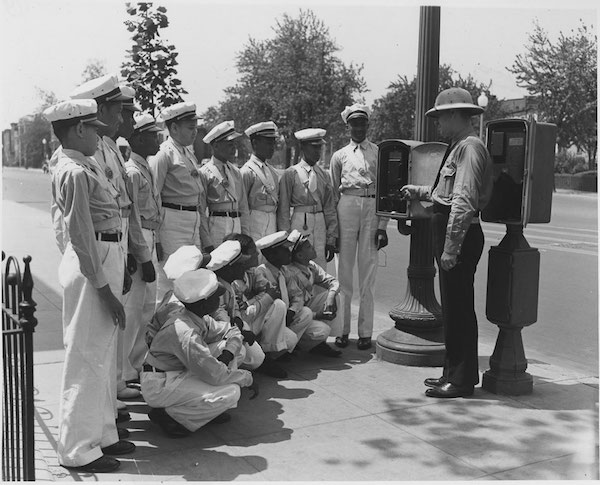

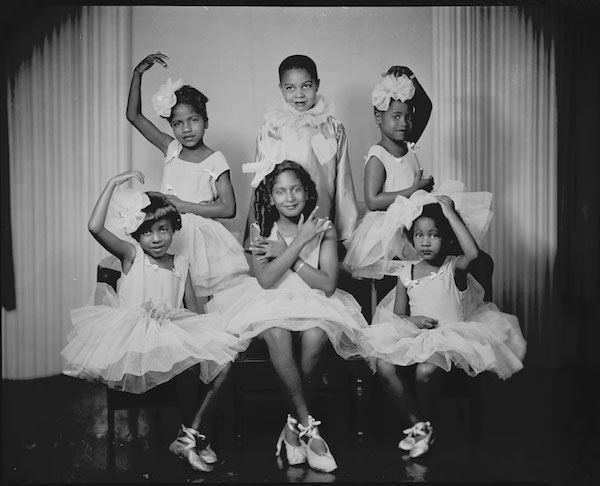

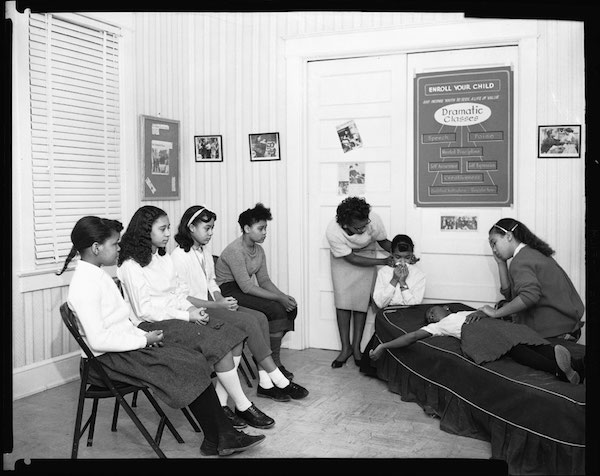

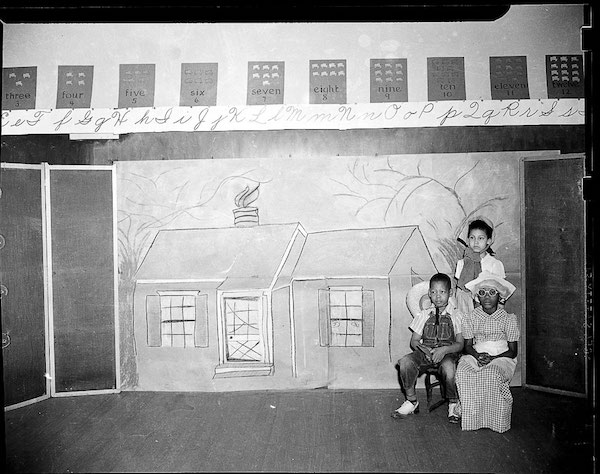

But in the Scurlock photos of schoolchildren, the “Scurlock look” is in full effect, in scenes carefully posed to evince the high-minded activities underway. A group of girls in their ballerina best. Boys receiving training in Safety Patrol. Tiny children propped on folding chairs paying rapt attention to their music instructor. And a drama class, complete with fainting couch and a large sign on the wall reading: “Enroll your child and inspire youth to seek a life of value.”

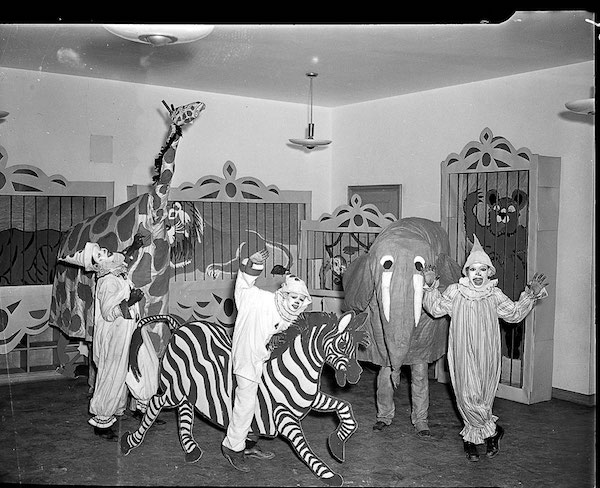

Of course, children often have their own ideas, and among the photos of children, also, are glimpses of a restless shaking-loose from the restraint of the Scurlock sensibility. A preschool girl smiles widely and directly into the camera as she prepares to cut her birthday cake. A group of boys dressed as clowns and circus animals express both ferocity and fun. Three thespians posed on the set of a school play bear expressions of grudging tolerance bordering on misery.

Who were these children and what were their lives like at that time? How do these moments sit in their memories? The information on many of the images in the collection is incomplete, and the Smithsonian welcomes any help in filling in the blanks. You can view much of the collection through their web portal, and also email them on specific photos. In this way, the story of the “Scurlock look” continues to unfold.

is editorial director for Zócalo Public Square.

Editor: Joe Mathews.

*Photos courtesy of Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905-1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

Add a Comment