In 1835, through an unlikely turn of events, the young United States became the beneficiary of the estate of one James Smithson, a British scientist of considerable means who had never set foot on American soil. The gift of $500,000 (about $12 million today) carried the stipulation that it be used to create an institution for the “increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

How amazing—and baffling—this windfall must have seemed! The responsibility was tremendous, in terms of the amount, the perception, and ultimately, the potential effect of this mandate on American culture. Indeed, it took Congress a full decade of debate before it agreed on what to do with the money.

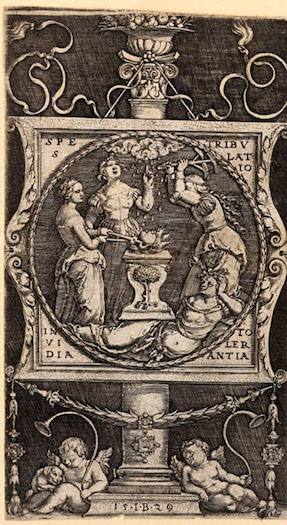

The Forge of the Heart.

Finally, in 1846, Congress settled on legislation that called for a museum, library, and gallery of art, together with scientific lectures and educational programs, to be supported by Smithson’s legacy.

It’s difficult today to imagine the atmosphere and attitudes of the U.S. at that time. We didn’t have much by way of cultural institutions. This was a full generation before the founding of major American art museums, which did not appear until the 1870s. America in 1846 was a challenging environment in which to develop a relatively “high culture” institution like the proposed Smithsonian. Nothing like it existed.

Practical men of science had to grasp this unique opportunity and make of it what they could. How would the nation construct its identity and take its place among the established civilizations of the Old World? European art galleries and museums were recognized as instruments of refinement and cultural patrimony. Politicians and educators who traveled abroad urged Americans to adopt more models of art and culture. At home, artists and civic leaders promoted the creation of such organizations as stabilizing forces that would influence public behavior and signal America’s growing cultural prowess.

But merely accepting Smithson’s gift raised controversy, as many in Congress and the nation harbored deeply anti-European feelings characterized by nativism and lingering resentment against British influences. Indiana Congressman Robert Dale Owen fought an initial plan to use Smithson’s bequest to create a national library, railing against the “dust and cobwebs” on the library shelves of European monarchies.

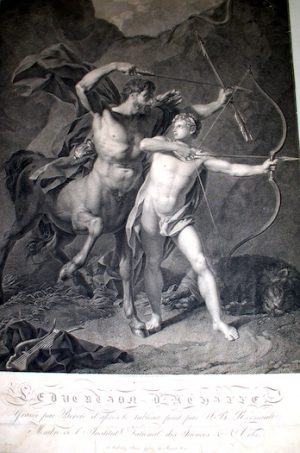

The Education of Achilles.

His views were countered by George Perkins Marsh, a Whig from Vermont, who proved a crucial advocate during the debates that framed the new institution.

Responding to Owen in April of 1846, Marsh argued eloquently before the House of Representatives that Smithson’s bequest paid the highest possible compliment to the nation, as it “aimed at promoting all knowledge for the common benefit of all.”

Marsh couldn’t know it at the time, but soon personal misfortune would contribute to the vision he described, and, ironically, provide a foundation on which to build the Smithsonian collection. In 1849 financial losses would compel him to sell much of his own substantial library. He offered some 1,300 European engravings and 300 art books to the Smithsonian—perhaps providing him some small comfort as he departed for a new post as U.S. Minister to Turkey.

Joseph Henry, the first Smithsonian Secretary and a distinguished scientist, approved the purchase of Marsh’s collection, which, though a departure from the Smithsonian’s then primarily scientific focus, formed the first public print collection in the nation and fulfilled the congressional mandate for a gallery of art.

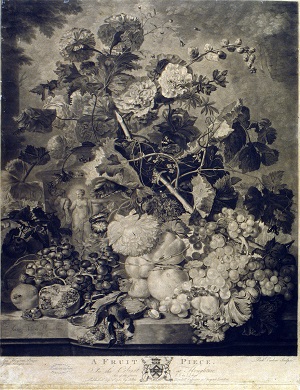

A Fruit Piece.

The purchase represented a remarkable if somewhat premature understanding within the Smithsonian of the potential role for a public art collection, even as the institution’s leaders were figuring out what that should mean for its evolving mandate and for the country as a whole.

Marsh’s collection included illustrated books and prints, both original old master impressions and finely engraved reproductions of painting and sculpture. Many of the books were compilations of engravings that reproduced works in the Louvre and other European galleries. His etching by Rembrandt, “Christ Healing the Sick,” was singled out for praise in the 1850 Smithsonian annual report, and its place in the building was noted in early guidebooks. In The Crayon, a new art magazine, Washington journalist Benjamin Perley Poore advised art lovers to seek out the Marsh prints and “enjoy their beauties.”

The purchase proved shrewd in another regard—engravings offered considerably more art for the money than painting or sculpture, while still providing a means of access to artistic expression. In the Smithsonian’s 1850 annual report, Librarian Charles C. Jewett observed that “engraving seems to be the only branch of the fine arts which we can, for the present, cultivate. One good picture or statue would cost more than a large collection of prints.”

Christ Healing the Sick.

The Smithsonian aligned its acquisition of the Marsh Collection with the traditional canon of European art, and the purchase occurred at a time when such images were becoming better known. References to prominent artists like Dürer and Rembrandt appeared with increasing frequency in popular literature, which addressed the merits of the fine arts. As the early republic developed a national identity, some of its citizens looked to artworks to provide models of beauty and to inspire decorum.

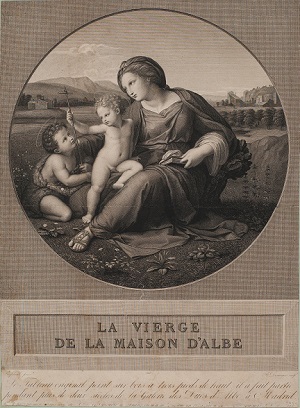

The Alba Madonna.

There was a noticeable spike in the mention of prints and printmakers in American periodicals beginning in the 1840s, and by the 1850s, the development of membership organizations like the Art Unions, and the growth of art stores, print sellers, and the engraving trade, enlarged the market for framing pieces and illustrated publications and demonstrated a rapidly growing taste for prints.

Symbolic figures such as Liberty, patriotic icons like George Washington, Shakespearean subjects, and other imagery appeared on everything from large, highly finished framing prints to banknotes and advertising. Family Bibles included plates based on European paintings, and the new genre of illustrated magazines and gift books brought pictorial references into the American home. Catharine Beecher and her sister Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote about specific prints that would be helpful for children to study. Other authors commented on the serenity and moral uplift provided by spending time with engravings like Raphael’s Transfiguration, and the numerous reproductions of his Sistine Madonna attest to the popularity of that image for a broad audience. The prints and books acquired from Marsh’s collection, in their own quiet way, were intended as a resource for the Smithsonian to establish its role as a positive influence on society.

Silenus.

Henry and Jewett believed that this “valuable collection of engravings,” together with the other programs of the new institution, would provide a locus for cultural authority and national pride. By the 1880s, the Smithsonian’s permanent graphic arts exhibition featured dozens of prints, plates, blocks, and tools, displayed to show how prints are made. It included prints from the Marsh Collection and other sources within a narrative structured by chronology and process to represent the progress of art.

Today, the Marsh Collection is treasured for its inherent cultural value as well as its connection to the debates that framed the Smithsonian. It set a standard of patrician quality and signaled acceptance of traditional European images. The Smithsonian’s broad approach, to represent in its exhibitions the incremental development of art as an industry, drew on Marsh’s personal interest in the history of engraving and enlarged on that concept to educate its visitors in the spirit of James Smithson’s bequest. The Marsh Collection formed an important foundation for the Smithsonian as an institution and for the country. In subtle but enduring ways, its legacy has shaped the culture and our relationship to art.

is Senior Curator of Graphic Arts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and the author of The First Smithsonian Collection: the European Engravings of George Perkins Marsh and the Role of Prints in the U.S. National Museum. An online catalogue of the Marsh Collection is available here.

All images courtesy of the Smithsonian. Interior images, in order of appearance:

1. The Forge of the Heart, engraved by the Master I.B. in 1529, is a complicated emblem print considered to be an allegory encouraging patience in matters of the heart.

2. The Education of Achilles, engraved by Charles-Clement Bervic in 1798, shows the centaur Chiron teaching the young Achilles how to shoot with a bow and arrow.

3. A Fruit Piece, engraved by Richard Earlom in 1781 after a 1723 painting by Jan van Huysum. This mezzotint and a companion print, A Flower Piece, were two of the most highly regarded images in George P. Marsh's copy of The Houghton Gallery.

4. Christ Healing the Sick, etched by Rembrandt van Rijn about 1648. The plate was reworked by Capt. William Baillie about 1775, and Marsh’s impression dates from the later edition.

5. The Alba Madonna, engraved by A. B. Denoyers in 1827 after Raphael's painting, was owned for many years by the Spanish dukes of Alba. It is now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

6. Silenus, in Greek mythology, was the tutor and companion to the wine god Dionysus. The engraving by S. A. Bolswert reproduced the original 17th-century painting by Anthony van Dyck.

Primary Editor: Sara Catania. Secondary Editor: Andrés Martinez.

Add a Comment