In the Wake of Pearl Harbor, a Secret Intel Report Could’ve Stopped the Internment Camps

The Tale of a Daring Night Raid That Vindicated Japanese Americans

A recreation of a typical living space inside internment barracks for a Japanese American family at Tule Lake in California during World War II. Photo courtesy of Andrea Pitzer.

In spring 1941, months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a team led by U.S. Naval Intelligence officer Kenneth Ringle broke into the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles.

One man stayed downstairs to guard the elevator while the rest snuck upstairs using skeleton keys to make their way to the back rooms. They brought along a safecracker—a convicted felon sprung for one night to help them—as well as local policemen and FBI agents, who set up patrols outside during the operation. Once the safe was open, Ringle’s crew photographed its contents item by item, putting everything back in place before leaving the building.

Though the United States had not yet entered the war, it had launched fledgling espionage efforts with an eye toward the possibility. The Navy had chosen Ringle to assess the Japanese threat in 1940 because he had previously lived and worked in Tokyo and was one of only a handful of U.S. sailors who could speak Japanese. He had gone on to build a network of contacts on the West Coast, determining which cultural organizations were harmless and which might be dangerous.

As a result of the break-in, Ringle made two key discoveries. The first was that he now possessed the consulate’s list of agents and secret codes. The second was that the Japanese government distrusted the Nisei, the generation born in the U.S. to Japanese immigrants, and was thus unlikely to make use of them as spies.

Ringle’s discoveries that night should have been powerful enough to prevent internment of Japanese Americans during the war. But, in wartime, his knowledge would prove an insufficient weapon against manufactured hysteria and deference to the Army.

After the devastation of Pearl Harbor, the Chief of Naval Operations assigned Ringle to write a report on the loyalty of U.S. residents of Japanese ancestry. He delivered a 10-page report six weeks after the attack stating that “the entire ‘Japanese Problem’ has been magnified out of its true proportion,” largely due to racial prejudice. “[T]he removal and internment in concentration camps of all citizens and residents of Japanese extraction … ,” he wrote, would be “not only unwarranted but very unwise.”

It was an insightful, detailed assessment. And nearly all of its recommendations would be ignored.

The story of the detention of nearly 120,000 residents of Japanese descent during World War II has become a mythic narrative, giving Americans the impression that the internment was an inevitable error born of simple ignorance and fear. Acting in haste after Pearl Harbor, the story goes, U.S. officials had no idea that concentration camps would be unnecessary and counterproductive.

But, in fact, senior cabinet members and the president himself had accurate information, and some did not favor internment.

The cinderblock jail at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California, which held Japanese American prisoners during World War II internment. Photo courtesy of Andrea Pitzer.

Long before the attack, the federal government had developed a plan for the treatment of enemy aliens in the event of war: targeted individuals would be rounded up and detained by the FBI, then provided a hearing before a review board, which would determine whether they should be given liberty without restriction, liberty on parole under the supervision of a sponsor, or continued detention. Just three days ahead of Pearl Harbor, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt—who also held the official position of assistant director for the Office of Civilian Defense—announced that noncitizens with “no criminal nor anti-American record” had nothing to fear in the event of war and would not be interned.

In the wake of the bombing, the government stuck to its plan at first. Ringle worked with FBI agents coordinating arrest squads in the hours after the attack, capturing those known or suspected to be spies from his lists. Restrictions and extra guards were put into place in sensitive military areas.

But other voices spread disinformation. A week later, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, who had advocated internment long before Pearl Harbor, accused Japanese Americans in Hawaii of betraying the nation, announcing without evidence that outside of Europe, “the most effective Fifth Column work of the entire war was done in Hawaii.”

On December 19, the man put in charge of the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command, Lieutenant General John DeWitt, first declared his intention to exile all Japanese Americans over the age of 13 from the West Coast. But he initially balked at his subordinates’ request to detain the entire Japanese American community, saying, “An American citizen, after all, is an American citizen.”

As he worked on his report after the bombing, Kenneth Ringle had the support of presidential advisor Curtis Munson, who advocated a measured response. The Washington Post concluded near the end of January that “The Alien Program Is Working Well,” noting that only those actually suspected of espionage had been arrested.

But in the background, other dramas were unfolding. U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle closed the Mexican and Canadian borders to all incoming Japanese individuals, and authorized raids of Japanese immigrant homes without warrants. In the days after Pearl Harbor, many Japanese Americans lost their jobs and lived in fear of violence or arrest. It was particularly bitter that white Americans accused Japanese immigrants of disloyalty, when U.S. court decisions had universally barred them from receiving citizenship for decades.

By the end of January 1942, two factions had emerged. The Roberts Commission, appointed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to investigate Pearl Harbor, delivered its report on January 23, making vague allegations of “Japanese spies.” The Commission did not distinguish the nature of the spying or whether it was committed by U.S. citizens or aliens. Yet rumors of espionage were seized on by opportunists to inflame prejudice across the country. The governor of California, Culbert Olson, announced that his state’s residents “don’t trust the Japanese, none of them.” In mid-February, journalist Walter Lippmann argued in a column that the lack of any real sabotage by Japanese residents along the coast to date was actually evidence of a future planned attack.

Pushed by zealous staff members, DeWitt requested control in early February over all citizens and aliens in zones established under his command. That spring, he would reverse his statement about an American citizen being an American citizen, explaining that, “A Jap is a Jap.”

Meanwhile, Ringle’s supporters pressed the case for restraint. On his side were crucial cabinet members: despite harsh measures taken against some noncitizens under his authorization, Attorney General Biddle backed measures focused on aliens rather than citizens. Even FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, a man not known for moderation, agreed that calls for universal internment rose out of political pressure rather than necessity.

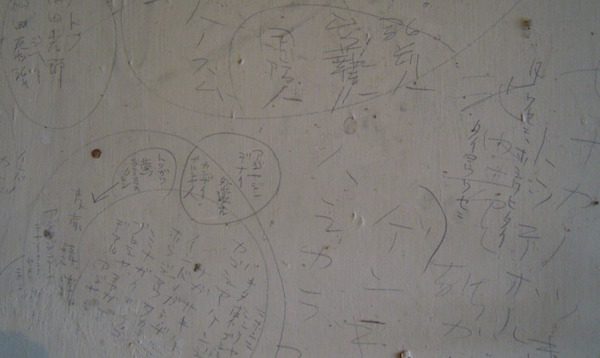

Japanese graffiti on the interior wall of a farmer’s shed in Tulelake, California. The shed originally housed Japanese American detainees during World War II. Photo courtesy of Andrea Pitzer.

Ringle turned in his assessment just days after the Roberts Commission filed its report, and it appeared that FDR agreed with Ringle’s supporters. But with Navy leadership unwilling to oppose the Army, by the time Ringle’s assessment wound its way to the White House three weeks later, public outrage and DeWitt’s demands had interceded.

Though Eleanor Roosevelt still stood against internment, her husband ultimately sided with DeWitt. On February 19, 1942, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, sealing the fate of not just Japanese aliens but also of some 70,000 Japanese American citizens of the United States. The Ringle Report had failed to block the Army’s drive for mass internment. But it would return to play a role in postwar events.

The shift toward internment began with the division of the exclusion zone into segments, in which Japanese American residents were given as little as two days’ notice to prepare for departure to temporary detention centers—mostly improvised camps at fairgrounds and racetracks. The War Relocation Authority was soon established, and before the end of 1942, purpose-built camps had been set up in isolated locations around the country, from Arkansas to Wyoming.

As Japanese Americans were forced from the West Coast, they had to sell their businesses and belongings, while the community argued over whether or not to protest. Nisei journalist James Omura condemned the policies of relocation and internment, drawing the wrath of Japanese American cultural organizations that did not want to appear disloyal to America. Other Japanese Americans launched legal challenges to the curfew and exclusion orders that barred them from their rights as citizens. The most famous among them, Korematsu v. United States, became the landmark Supreme Court case on the question of wartime internment.

When Korematsu was heard in 1944, a government attorney alerted U.S. Solicitor General Charles Fahy to the existence of the Ringle Report, noting that failure to acknowledge it in his filings to the Supreme Court “might approximate the suppression of evidence.” But Fahy ignored this warning and directly indicated to the court that all U.S. government and military assessments were unanimous in support of internment.

The Supreme Court expressed discomfort with mass internment’s failure to address individual guilt or innocence, but was already prone to defer to the executive branch and military leaders in wartime. Unaware of the additional evidence which had been withheld, the court accepted the Army’s argument of the “military necessity” of detention.

The public and the Court would not learn of the solicitor general’s omission until decades later, when a reporter discovered material in archived files. By then, Ringle was dead, with a funeral wreath sent to his widow by the Japanese American community in honor of his efforts to protect them.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that his report, which should have settled the question of universal internment, became the central piece of evidence used by the original plaintiffs to demand justice in court. And it would take three more decades until acting U.S. Solicitor General Neal Katyal wrote a public repudiation in 2011 of his predecessor’s actions in Korematsu.

If the Ringle Report could not prevent the tragedies that had been suffered—the degradation of U.S. citizens, the financial losses, and mass dislocation—its reappearance did at least set the historical record straight.

Andrea Pitzer is the author of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov and is currently writing One Long Night, a century-long history of concentration camps.

This essay is part of a Zócalo Inquiry, Why We're Still Reckoning With Japanese American Internment.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Joe Mathews.

Add a Comment