A populist desire for “reform” runs deep in the psyche of American voters. Every few decades, a presidential candidate channels this rebellious spirit. Andrew Jackson was such a candidate in 1828. So were William Henry Harrison in 1840, Abraham Lincoln in 1860, William Jennings Bryan in 1896, Teddy Roosevelt in 1912, Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, Jimmy Carter in 1976, and Barack Obama in 2008.

But no candidate for President carried the reform banner for honesty and competence more naturally, or tragically, than Horace Greeley. In 1872, Greeley was the nation’s leading newspaper publisher and editor. His incisive analysis of contentious issues, dramatic, witty, and prolific writing, his insertion of literary content, and appeal for higher journalistic standards, elevated the entire newspaper profession. In his words: “Fame is a vapor, popularity an accident, and riches take wings. Only one thing endures and that is character.”

For three decades, Greeley was among the loudest advocates for important and sometimes odd causes. The New York Tribune, which he founded in 1841 at age 30, was “anti-war, anti-slavery, anti-rum, anti-tobacco, anti-seduction, anti-grogshop, anti-brothel, and anti-gambling house.”

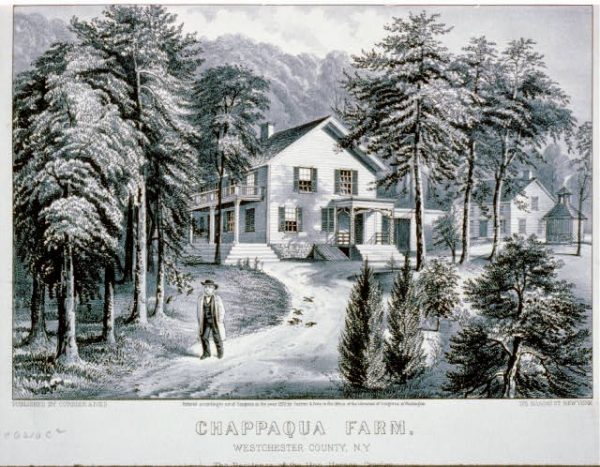

Greeley also advocated for cooperative economic movements and was called “The Farmer of Chappaqua” because he tended several acres near that small town north of New York City. Expansion of the free common school was one of his deepest passions—though his family’s meager circumstances afforded him just three years of schooling, he read the entire Bible by age five. He promoted trade unions and was the first president of the Printers’ Union. “Honest Horace” believed in American progress and good government.

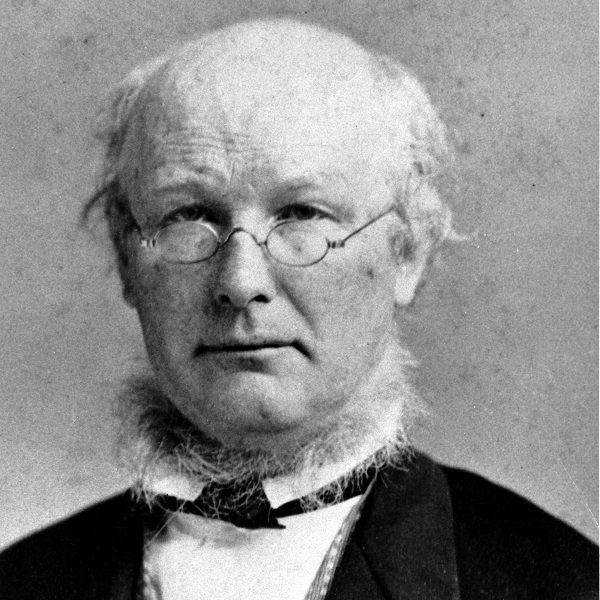

Horace Greeley, 1868.

Then he entered it. In 1848-1849, he was appointed to fill a vacancy in Congress for three months as a Whig. In Washington, he introduced the first bill to give small tracts of free government land to settlers. But when he exposed abuses in reimbursement to members of Congress for travel, he became the target of their personal abuse. By 1852, the Whigs were breaking apart as a political party over the question of slavery, so Greeley opted not to seek re-election.

In any case, he was an unlikely politician. His appearance alone was alarming. He was tall and angular with long stringy hair, chin whiskers, and wire-rim glasses. He carelessly dressed in a long linen coat called a Duster, and wore a tall white hat—his trademark. As the nation’s leading reformer and political oracle, Greeley had many detractors who called him a moral zealot and “scatter-brained.”

In 1854, Greeley was among those who, along with Joseph Medill and Alvan B. Bovay, gave the Republican party its illustrious name—co-founding it on a platform opposing expansion of slavery. He churned out editorials in favor of the first two Republican presidential candidates, John C. Fremont and Abraham Lincoln. But in 1868, his support for General Ulysses S. Grant was lukewarm—he’d condemned Grant as a “drunk” during the Civil War.

Horace Greeley and family.

Greeley’s fears about Grant’s competence were quickly realized. The 18th President was cozy with Wall Street speculators and handed out government positions to family, friends, and army acquaintances, some of whom engaged in corruption that soiled his administration.

On May 1, 1872, a month before President Grant’s re-nomination at the Republican convention in Philadelphia, a desperate collection of several hundred “anyone but Grant” Republicans—Liberal Republicans, they called themselves—convened in Cincinnati. “The Civil Service of the government has become a mere instrument of partisan tyranny and personal ambition and an object of self greed,” their platform charged. The reform party also denounced Grant’s “hard money” policies that hurt western farmers and helped eastern bankers who held their debt.

The President had agreed with Greeley’s editorial advice and persuaded Congress to pass the anti-Ku Klux Klan Act. But Liberal Republicans thought the law put too much power in the hands of the federal government to suppress individual rights. They called for “universal amnesty” for Southerners, and feared Grant’s tough Reconstruction policy would fuel long-term hatreds and turn the South against Republicans for decades.

Having adopted a platform of principles, the Liberal Republicans turned to the main business of nominating a presidential candidate. Greeley hoped it would be him and had sent his top editorial assistant, Whitelaw Reid, to Cincinnati to help organize support. On the convention’s first ballot, Charles Francis Adams, son of one president and grandson of another, took the lead and Greeley came in second.

But Adams had sailed for a European vacation and had refused to say if he would accept the nomination. So on the second ballot, the New York publisher took a two-vote lead, which continued to build until he won a majority of delegates on the sixth ballot.

Chappaqua Farm, Westchester County, N.Y.: The residence of the Hon. Horace Greeley. By Currier & Ives, 1872.

Some 10,000 Greeley supporters greeted news of his nomination with a “monster rally” in New York City under a fire sign declaring him, “The People’s Choice.” Greeley clubs sprung up across the country and supporters donned “the white hat of peace,” like the one worn by their disheveled political hero.

A month after the regular Republicans re-nominated President Grant in June, Democrats convened in Baltimore for the strangest convention in party history: it lasted just six hours. Party leaders could not agree on a Democrat to become nominee. But they were determined to find someone to challenge President Grant, whose military occupation of southern states they hated. And Greeley, though not a Democrat (he’d been a bitter critic of Democrats for decades) opposed Grant forcefully. There was no prohibition against becoming the nominee of two parties. So the Democrats, with fewer other options, turned to Greeley. The Democratic party adopted the Liberal Republican platform, including support of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments that had outlawed slavery and given citizenship to former captives.

Greeley’s campaign was frenetic. He traveled by carriage and train through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana, drawing massive crowds (who wanted to see the eccentric reformer) and delivering upwards of 200 speeches—more than any candidate before him.

“Let us forget that we have fought,” he exhorted. “Let us remember that we have made peace…” He called for a “New Departure” to heal the wounds of Civil War. He answered hundreds of letters, turned out campaign literature, and met with hordes of well-wishers. By mid-summer Greeley’s supporters were confident that his message of national reconciliation was taking hold and that he would win.

But the incumbent president counter-attacked. Grant-backing hecklers disrupted Greeley’s rallies, relentlessly denouncing him as “Old Chappaquack” and a “Know-Nothing.” Cartoonist Thomas Nast lampooned him on the pages of Harper’s Weekly. One caricatured him shaking hands with John Wilkes Booth over the grave of Lincoln. The cartoon stung—Greeley had been among those who posted bail for Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

Horace Greeley honored on a 1961 U.S. postage stamp.

During the summer, the strain of the campaign and the attacks proved too much. Greeley was sidelined with “brain fever.” Then, a week before the election, his invalid wife Mary died. “I am not dead, but I wish I were,” Greeley told a friend.

On election day, Nov. 5, 1872, some Liberal Republicans abandoned Greeley because he cared little about civil service reform and did not support the party’s free trade sentiments. And many Democrats couldn’t bring themselves to vote for their recent rival. Grant, still a war hero to many American people, attracted nearly 3.6 million votes or 55.6 percent of the total. Greeley swayed 2.8 million voters. Broken and humiliated by his loss, Greeley wrote, “I stand naked before God, the most utterly, hopelessly wretched, and undone of all who ever lived.” He was committed to a sanitarium where he died on November 29, just three weeks after the election.

On Dec. 4, 1872, President Grant’s carriage led the editor’s funeral procession down Fifth Avenue. Tens of thousands of admirers joined the cortege, including Vice President Henry Wilson, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, numerous Congressmen and the city’s mayor. Horace Greeley had lost an election, but the nation grieved its loss of the man poet John Greenleaf Whittier called “our later Franklin.” Grant’s second term was marred by even more scandals than the first. Reform would have to wait for another day.

is the author of three books on presidential conventions and elections and teaches at DePaul University in Chicago.

This essay is part of a What It Means to Be American Inquiry, U.S. Presidential Elections Have Always Been Crazy.

Primary Editor: Sara Catania. Secondary Editor: Joe Mathews.

*Lead image courtesy of Dave Taylor/BoothieBarn. First interior image courtesy of Associated Press. Second and third interior images courtesy of Library of Congress. Fourth interior image in the public domain.

Add a Comment