Was Wounded Knee a Battle for Religious Freedom?

By Clamping Down on the Indian Ghost Dance, the U.S. Government Sparked a Tragedy

Sioux tribespeople taking part in the Ghost Dance, 1890, drawn by Frederic Remington based on sketches from Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

The Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 appears in many history textbooks as the “end of the Indian Wars” and a signal moment in the closing of the Western frontier. The atrocity had many causes, but its immediate one was the U.S. government’s effort to ban a religion: the Ghost Dance, a new Indian faith that had swept Western reservations over the previous year.

The history of this episode—in which the U.S. Army opened fire on a mostly unarmed village of Minneconjou Lakotas, or Western Sioux, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota—teaches us about the moral perils of abandoning religious freedom. Although the First Amendment guarantees freedom of conscience, only in recent decades did that protection extend to American Indian ceremony and belief.

For most of U.S. history, the federal government sought to assimilate native peoples by eradicating their religious ceremonies and belief systems. These efforts increased with all-out campaigns to turn Indians into Protestant, English-speaking farmers in the closing years of the 19th century. Under government regulations that took effect in 1883, the Department of Interior banned “heathenish” (meaning virtually all) Indian dances, in an effort to force conversion to Christianity.

Thus, customary ceremonies that once brought spiritual relief to Lakotas, such as the Sun Dance, became illegal. At the same time, reservations grew dramatically poorer. Congress’ 1889 decision to reduce food rations to Lakota Sioux, bringing many to the point of starvation, and to strip Indians of most of their reservation lands, increased native peoples’ sense of desperation. On other reservations, among Arapahos and Cheyennes, for example, similar pressures also contributed to a growing feeling of crisis.

It was at this point, in the fall of 1889, that the new teachings of what became known as the Ghost Dance religion began to energize believers among Lakotas and in other Indian communities, especially on the Great Plains. Many greeted its teachings with joy. This was no violent uprising: Armed resistance to U.S. authority had ended in 1877. For well over a decade, Lakotas had peacefully occupied reservations in South Dakota and North Dakota. Other peoples who took up the Ghost Dance, such as Arapahos and Cheyennes, had lived on reservations in Montana, Oklahoma, and elsewhere for even longer.

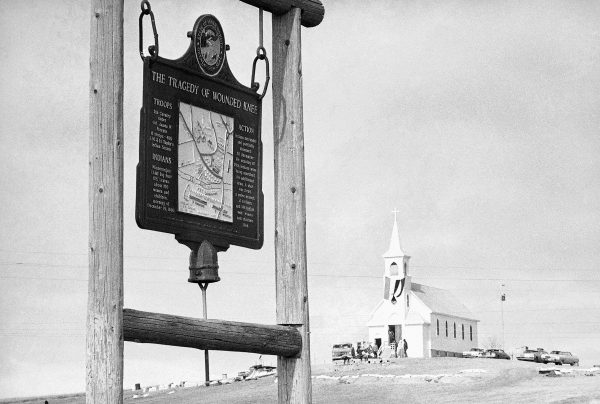

A view of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, date unknown. Photo courtesy of Associated Press.

None of these peoples were threatening hostility. What they sought was redemption from their suffering, and the new religion promised it. Tribal members passed along rumors of an Indian messiah who would come in the spring, bringing a new earth, on which believers would find no white people, but abundant buffalo and horses. For this wondrous event to transpire, said the evangelists, believers must adopt a new ceremony: a sacred dance in which participants held hands and turned in a large circle. Among Lakotas, the circle turned at an ever faster pace until some dancers collapsed into trances. On awaking, many recounted visions of the afterworld and encounters with spirits of their departed kin and friends.

At its peak, perhaps one in three Lakotas joined the dance circle, and the exuberance of believers was spectacular, with hundreds dancing at any moment and dozens falling into visions. But to U.S. government officials responsible for administering the reservations, the excitement could only mean trouble. “The dance is indecent, demoralizing, and disgusting,” wrote one. “I think,” wrote another, “steps should be taken to stop it.”

Why did the dancing elicit such strong condemnation? The wave of Ghost Dance enthusiasm had run headlong into the government’s policy of assimilation, the ongoing effort to force Indians to look and behave like Protestant white people. While most officials recognized Ghost Dancers were peaceful, they were nonetheless perturbed by the sudden appearance of the large circles of ecstatic dancers. The rhythmic movement of bodies proved to white observers that Indians were refusing to assimilate, to abandon old religions and embrace Christianity. The Ghost Dance looked like dangerous backsliding toward “paganism.”

And yet, to many Indians and even a few white defenders, the Ghost Dance religion also looked a lot like Christianity. Some white observers compared the dance to evangelical camp meetings, and one urged officials to let Ghost Dancers “worship God as they please.” The religion, after all, promised the coming of a messiah, who some adherents called “Christ,” and some of its teachings were not that different from those of Christianity.

The prophet of the Ghost Dance was a Northern Paiute named Wovoka, or Jack Wilson, who hailed from Nevada. By 1889, Northern Paiutes had long since entered the Nevada workforce as teamsters, road graders, builders, domestic servants, and general rural laborers. Wovoka himself was a well-regarded ranch hand. According to multiple accounts from the period, he instructed his followers not only to dance, but to love one another, keep the peace, and tell the truth. He also told Ghost Dancers to take up wage labor, or as he put it, “work for white men.” They should send children to school, attend Christian churches (“all these churches are mine,” Wovoka counseled), and become farmers. Such teachings were transmitted to distant followers on the Plains. Lakota evangelists, too, instructed their followers, “Send your children to school and get farms to live on.”

The Ghost Dance religion was no militant rejection of American authority, but an effort to graft Indian culture on to new ways of living, and to the new economy of wage work, farming, and education that the reservation era demanded. But to government officials, the dancing was a sign of religious dissent and had to be stopped.

The wave of Ghost Dance enthusiasm had run headlong into the government’s policy of assimilation, the ongoing effort to force Indians to look and behave like Protestant white people.

When Ghost Dancing continued throughout 1890, President Benjamin Harrison sent in the army. On December 28, some 500 heavily-armed cavalry accepted the surrender of a village of 300 elderly Minneconjous, women, children, and some lightly-armed men. The next morning, as troops were carrying out orders to disarm their prisoners, a gun fired, probably by accident. Nobody was hurt, but an impulsive commanding officer ordered his troops to open fire. By the time the shooting stopped, some 200 Lakotas lay dead and dying. In the aftermath, a brief shooting war finally erupted, with skirmishes taking the lives of dozens of Indians and a handful of soldiers before Lakotas once more surrendered their arms.

To this day, the pain of Wounded Knee is still deeply felt within the Pine Ridge community and by descendants of the victims. The stain of the Wounded Knee Massacre remains on the army and the U.S. government.

But efforts to suppress the Ghost Dance religion had the opposite effect. Army violence convinced many believers that its prophecies must be true, and that the government was trying to stop them from being fulfilled. Why would the government want to stop prayers to the Messiah, unless white people knew the Messiah was real? Clearly, said believers, the government knew the Messiah was coming.

After a brief period, secret Ghost Dances returned to South Dakota. Elsewhere, dances among Southern Arapahos and Southern Cheyennes took on renewed energy. Among some peoples, Ghost Dances were held regularly through the 1920s. Across many different Indian reservations, the ceremony and its teachings endure to this day.

Only in the late 20th century would Indian people begin to secure limited rights to observe their own religions. As they have done so, our memories of assimilation campaigns and their tragic consequences have faded. But as Americans still debate the merits of religious freedom, the Ghost Dancers of Wounded Knee remind us of the terrible price of suppressing belief.

Louis S. Warren, is the W. Turrentine Jackson Professor of Western U.S. History at the University of California, Davis, and the author most recently of God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America (Basic, 2017).

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment