I remember most clearly the things that aren’t here anymore, the things that I saw as a child in our neighborhood in South Los Angeles.

In 1937, when I was seven, we lived in a white, wood frame house on East 61st Street. It had a front lawn and a big backyard with an alley behind it. Main Street was a few feet west, with a print shop I visited because the owner gave away writing tablets and the Princess Theater where we spent weekend afternoons. To the east was a little street named Wall Street with a corner grocery store. Toward the end of the month when mother ran short of cash, the grocer was happy to put any needed purchases “on the bill” until payday. The farthest south we ever ventured was 64th Street where our school, St. Columbkille’s, stood.

But in those days, you didn’t need to take the streetcar to meet the world; so many memorable people and things arrived at your door. With few exceptions, like going to the neighborhood grocery store, we didn’t have to leave home to purchase goods; vendors came to us. Amazon may be onto something, but it isn’t something new.

I recall the greengrocer who visited in a horse-drawn cart selling fruit and vegetables. The driver would raise the side panels of his vehicle to display his selection, still in their packing boxes. In those pre-spraying days, anyone eating an apricot was best advised to split it open and not bite into it. Tiny worms often inhabited the area around the pit.

The Fuller Brush man was a regular visitor at most houses. He came laden with the latest thing in brushes to make our lives easier—brushes for the floor, for the kitchen, and bathrooms. Since I was the oldest child in our family, it was my job to prepare bottles of milk for my infant brothers and sisters. I was happy to discover that the Fuller Brush man sold bottle brushes to assist me in washing the bottles. The Fuller Brush man became part of American popular culture and achieved the ultimate—a movie that starred a top comic of his day, Red Skelton, as the Fuller Brush Man.

In an era when not every home had a refrigerator, the iceman delivered. In our neighborhood it was the Kirker Ice Company whose plant was at 5930 South Main St. Once a week, a household that needed ice would place a card with a large ‘K’ printed on it in the window—a signal to the ice man that he should stop and deliver. The iceman would grab a block of ice with heavy-duty tongs, fling it onto his shoulder where it rested on a pad of heavy leather, and lug it to the kitchen icebox where he deposited it in its compartment. The system worked fine except that the melting water often overflowed the pan we placed on the floor under the box, creating a sloppy mess.

The Helms man often announced his arrival with three toots of his whistle. The bread he sold didn’t interest the children who gathered around his distinctive yellow van. What attracted us were the sweets: doughnuts, turnovers, pies, eclairs, and more. He stored them in oversized drawers and removed a requested item by taking a piece of tissue paper and lifting the item as if it were a precious object. Even kids who weren’t buying gathered around to enjoy the show and inhale the accompanying fragrance.

Farmer Brothers sold coffee and tea door-to-door. Occasionally Farmers ran promotions that featured dishware at reasonable prices; it was decorated with delicate paintings of autumn leaves. I hadn’t seen any of them for many years until I recently spotted a bowl at a Pasadena flea market. The sight instantly took me back decades. Of course, I bought it. Marcel Proust evoked memories of his childhood with the taste of chamomile tea and madeleines. My bowl serves that purpose for me.

Milk was delivered to homes in the early mornings by men wearing white uniforms

and lifting glass quart bottles in a metal carrier that fitted six bottles. Jessup, Knudsen, and Adohr were the important dairies then. During World War II, a song named “Milkman, Keep Those Bottles Quiet” became very popular. It was sung by a worker in a defense plant whose sleep the milkman disturbed.

Milkman, keep those bottles quiet,

Can’t use that jive on my milk diet.

Been jumping on the swing shift all right,

Turning out my quota all night.Been knocking out a fast tank all day,

Boy, you blast my wig with those clinks,

And I got to catch my 40 winks.

During the summer, the neighborhood would be visited at least once by a photographer who arrived leading a pony that was laden with a large format camera and tripod. There was no need for him to broadcast his presence. Children caught sight of him and ran home to announce his arrival. Doting mothers who wanted photographs of their offspring came out of their houses to hail him. The photographer came prepared for his photo sessions with a pair of sheepskin cowboy chaps, a belt and holster with a six-shooter, a large bandana, and a cowboy hat. My mother was a customer and the family photo album contains photos of both my brother Raul and me posing warily on ponies, doing our utmost to smile. From that day to this, I have not gotten on another horse, of whatever size.

Insurance salesmen generally knocked on our door in the late evening when the entire family would be there to decide on whether to purchase a policy. Mother was a firm believer in insurance and it took no persuasive speech by the Prudential man to convince her to buy a policy. The salesman would come by monthly to collect the premiums, using his thick account book to record the payment and issue a receipt. When the insured, my father, died, payments on his policy were in arrears but mother contacted the agent anyway. He assured her that if she made up the late payments, the company would pay off as they had contracted. She did and they did. Prudential paid her $500, a not inconsiderable sum at the time.

These days when nearly everyone carries a personal telephone, it is difficult to imagine a time when most houses were not equipped with telephone jacks and didn’t have phones. I didn’t use a phone until I was 10 years old.

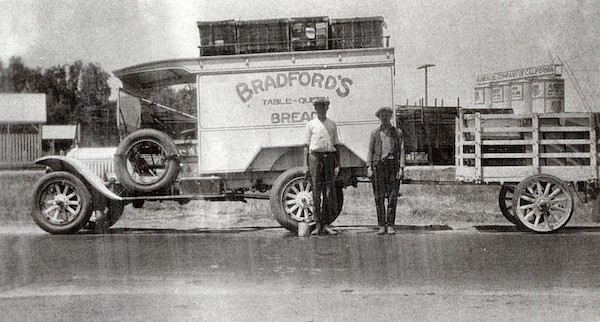

Bradford’s Bread Truck, Irvine Ranch, circa 1920.

For the many Americans in our situation—that is, phoneless—Western Union offered a scene that Ingmar Bergman might have thought up. A uniformed Western Union employee

would knock on the door, usually at night. He carried a telegram that had a black border around the envelope that contained it. That border gave us immediate notice that someone close to the family had died. I witnessed that scene several times as a child and can testify that the interim between seeing the black border and learning the name of the deceased seemed a very long time.

Other itinerant salesmen included the knife and scissors sharpener who wheeled his little cart with its grinding wheel down our street periodically. A music man came by the house one evening to try his luck at selling music instruments. He demonstrated a steel guitar that I liked a lot. I asked my parents whether we could buy the guitar and if I could take the lessons that came with it. One parent agreed; the other didn’t. I still can’t play the guitar.

In the summer, the ice cream man drove his truck down the street playing a tune on his loudspeaker. Chocolate-covered Good Humor bars and Eskimo Pies were beyond our budget. What helped cool us off in hot weather were big slices of cold watermelon and frosty pitchers of lemonade that mother prepared for us.

A woman wearing a flowing, flowery skirt knocked on our door one day. She advertised herself as a fortune teller. Mother consulted her and I can only hope that she got some good news for her money. Vacuum cleaner salesmen dropped by to make their pitches. Mother liked the machine the Electrolux man demonstrated. She bought it. It was expensive but mother appreciated quality and never bought any vacuum cleaner that wasn’t an Electrolux.

Now that I think about it, both my brother, Raul, and I were members of the selling class. On Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings, we’d pick up our quota of newspapers and roam the streets around our neighborhood, then around 62nd and San Pedro Streets, pulling our wagon and hawking our newspapers. To announce our presence, we developed a sing-song, “Exxxxxaminer, Times, Paperrrr!” We were thrilled when we got home with our pockets bulging with coins. It was a fun way to augment the family income.

Our family doctor was E.C. Deming, whose office was located at 6806 South Broadway. Dr. Deming made house calls for which he charged $2. In 1939 mother called him to our house to check the condition of a 9-year-old boy who was experiencing pain in the groin area. Father was less than enthusiastic about my going to the hospital, but when Deming mentioned the possible consequences of a ruptured appendix, I was allowed to go. The operation, at Children’s Hospital, was successful.

Many people, overwhelmingly men, worked as itinerant salesmen in the 1930s; I’m reminded that in 1937 the U.S. unemployment rate reached 17 percent. Those men took jobs that may not have been their first choice—they did so because there were no other employment options.

These vendors were eventually replaced as consumers took to driving their cars to malls, often on crowded streets and freeways, packing multi-storied, fortress-like parking structures to full capacity.

How long will it be before shopping malls and their parking lots join the list of things that aren’t here anymore, and that people of a certain age look back upon with nostalgia?

taught in local Los Angeles schools for 41 years, 35 of them at Los Angeles Valley College.

This essay is part of South Los Angeles: Can the Site of America's Worst Modern Riots Save an Entire City?, a special project of Zócalo Public Square and The California Wellness Foundation.

Primary Editor: Joe Mathews. Secondary Editor: Andrés Martinez.

*Lead photo courtesy of Library of Congress. Interior photo courtesy of Orange County Archives/Flickr.

Add a Comment