There are few symbols of pure Americana more potent than the Disney theme parks. To walk down any of the destinations’ manicured Main Streets, U.S.A.—as hundreds of thousands of visitors do each day—is to walk though a particular vision of America’s collective memory. It’s small-town values. It’s optimism. It’s energy. It’s innovation. It’s a certain kind of innocence. It is by design, the story of the “American Way”—and one that has played a dominant role in shaping the collective memory of American history.

There are few symbols of pure Americana more potent than the Disney theme parks. To walk down any of the destinations’ manicured Main Streets, U.S.A.—as hundreds of thousands of visitors do each day—is to walk though a particular vision of America’s collective memory. It’s small-town values. It’s optimism. It’s energy. It’s innovation. It’s a certain kind of innocence. It is by design, the story of the “American Way”—and one that has played a dominant role in shaping the collective memory of American history.

Though Disney Parks today are well-established cultural icons, the Walt Disney Company’s start as an interpreter of American history and ideals began long before it opened the gates of Disneyland or Disney World (1955 and 1971, respectively). From its creation in 1923 as “The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio,” the Disney operation was producing films that echoed Americans’ ideal version of themselves. Often set in a glorified 19th century rural American heartland, these animations featured a hero (usually the indomitable Mickey Mouse) whose strong work ethic and bravery in the face of risk always found the “little guy” and “common man” triumphant over his foe. Such optimistic sentiment held great appeal in the country’s Depression years, and most certainly led Mickey and company to become household names.

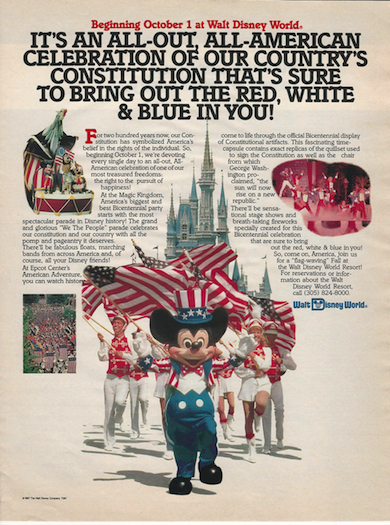

Promotional poster from Life Magazine for Disney World’s 1987 celebration of the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution. Courtesy of Bethanee Bemis.

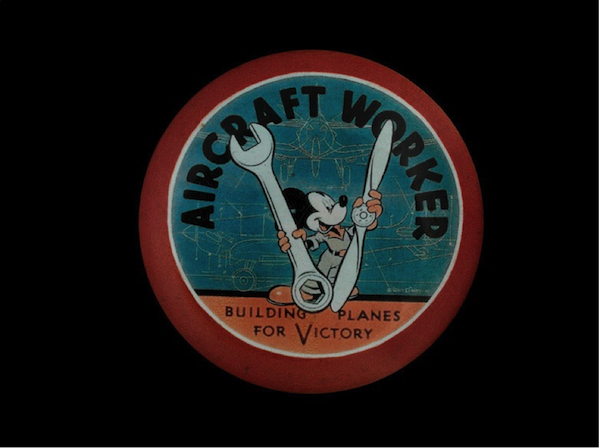

By World War II, the company was cementing its association with the “American Way” by producing propaganda films and war-related goods that served the U.S. cause. Disney characters appeared on war bonds, posters, and on more than a thousand military unit insignia. They also appeared in short patriotic cartoons: The Spirit of ’43 has Donald Duck expounding on the importance of paying taxes; Donald Gets Drafted, shows, as expected, the irascible cartoon waterfowl getting drafted. Donald Duck in particular became so well recognized as an American symbol during the war that in February, 1943 The New York Times called him “a salesman of the American Way.” For their promotion of wartime allegiance and good citizenship, Mickey Mouse and friends joined the ranks of the Statue of Liberty and Uncle Sam as faces of our nation.

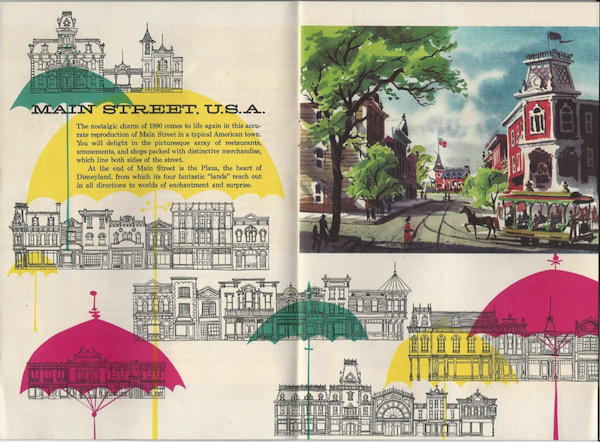

This narrative of upholding American values continued at the brand’s theme parks, where Walt Disney translated it into a physical experience using American folk history. “Disneyland,” he said at the park’s grand opening, “is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams, and the hard facts that have created America.” Visitors are made to feel as if they are stepping into carefully curated moments of history, ones chosen to fit a tidy narrative that highlights the nation’s past and future commitment to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It celebrates a simple story that tells us that through hard work—and perhaps a bit of pixie dust—any American can make their dreams come true.

Main Street U.S.A.’s manicured small-town charm and bustling shops boast of American optimism and enterprise. The colonial-themed Liberty Square teems with symbols of the nation’s commitment to independence, even when it requires a fight. Its centerpiece, the Hall of Presidents, provides a stirring homage to our government and its illustrious leaders. And while Frontierland’s cowboys and pioneers harken back to the rugged individualism of the Old West, Tomorrowland’s space age attractions point ahead to America’s constant eye to a better future and the conquest of new challenges. American heroes like Abraham Lincoln, Paul Revere, and Davy Crockett—whose legends are repeated to us in childhood—are brought to “life” here through Disney magic.

The pocket map, “The Story of Disneyland with a complete guide to Fantasyland, Tomorrowland, Adventureland, Frontierland, Main St. U.S.A.” from 1955. Courtesy of Bethanee Bemis.

Visitors not just from all over the country, but from around the world, can find themselves standing amidst Disney’s version of America’s past, creating a sense of collective memory in all who visit. It’s perhaps telling that the parks have been popular destinations for not only four sitting U.S. presidents over the decades (Carter, Reagan, H.W. Bush, and Obama), but also foreign heads of state—from Prime Minister Nehru of India to the Shah of Iran to Khrushchev (who was famously barred from visiting)–hoping to get insight into American culture.

Fittingly, in 1976, as the nation celebrated the 200-year anniversary of Independence Day, the Disney Parks staged a 15-month bicoastal extravaganza of Americana, “America on Parade,” which Disney dubbed “America’s Biggest and Best Bicentennial Party.” The festivities included special touches such as television programs, books, and records.

The stars of the show were the parks’ daily parades—50 floats and more than 150 characters representing “the people of America”. They were seen by an estimated 25 million park visitors, making it one of the largest shared celebrations across the nation (and were even designated “official bicentennial events” by the U.S. government). The grand show helped solidify the theme park’s place in the minds of Americans as spaces not only for family-friendly vacation destinations, but as ones where they could come together to share cultural and historical heritage.

WWII aircraft worker’s pin featuring Mickey Mouse, from the Lockheed Martin Aircraft Plant in Burbank, CA. Courtesy of Bethanee Bemis.

To be sure, Disney’s unique ability to appropriate and transform American history in its own nostalgia-tinged image—what has come to be called “Disneyfication”— has drawn significant criticism. Its idealized imaginings of the country’s past can certainly strip out its more complicated, controversial, and unsavory elements in favor of a simpler, sunnier story.

But when it comes to collective memory, it must be noted that the past can be remembered one way and exist factually in another, and that many different versions can have their place in the American mind. For many park visitors, the value of “Disneyfied” history is not in its factual accuracy—or lack thereof. The importance of “Disney’s American history” is in how it gives life to a folk history we would like to have, one that gives us a sense of optimism and unity. It makes easily accessible a version of American history that shows visitors less the nation that we have been than the nation that we want to be, and, indeed, hope that we are.

Even as characters change and Tomorrowland becomes an artifact of yesterday, Disneyland and Disney World continue to be touchstones of American collective memory. From annual Fourth of July celebrations to contemporary additions to the Hall of Presidents, from a 1987 celebration of the Constitution’s bicentennial, to the swearing in of new citizens on Main Street, U.S.A., the parks have established themselves as places to celebrate shared memories and civic pride—and allow it to evolve and expand.

is a museum specialist in the political history division at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Primary Editor: Sara Catania. Secondary Editor: Kirsten Berg.

*Lead image: Souvenir Disneyland scrapbook with Frontierland’s iconic symbols from 1955. All images courtesy of Bethanee Bemis.

Add a Comment