How Sears Industrialized, Suburbanized, and Fractured the American Economy

The Iconic Retail Giant Turned Thrift into Profit, But Couldn’t Keep Pace with Modern Consumer Culture

A Sears Outlet Store in Downers Grove, Illinois shuttered its doors in September, 1993. Photo by Charles Bennett/Associated Press.

The lifetime of Sears has spanned, and embodied, the rise of modern American consumer culture. The 130-year-old mass merchandiser that was once the largest retailer in the United States is part of the fabric of American society.

From its start as a 19th-century mail-order firm, to its heyday on Main Street and in suburban malls, and from its late 20th-century reorientation toward credit and financial products to its attempted return to its original retail identity, Sears has mirrored the ups and downs of the American economy. It was a distribution arm of industrial America. It drove the suburbanizing wedge of postwar shopping malls. It helped atomize the industrial economy through manufacturer outsourcing in the 1970s and 1980s. It played a key role in the diffusion of mass consumer culture and commercial values. For better and for worse, Sears is a symbol of American capitalism.

By the early 20th century, Sears already was a household name across the United States, one that represented rural thrift and industry as well as material abundance and consumer pleasures. The company was founded as a modest mail-order retailer of watches in the 1880s by Richard W. Sears and Alvah C. Roebuck. Julius Rosenwald, a Chicago clothing merchant who became a partner in the firm in 1895, directed its rapid growth, expanding into new products and ever-broader territory. Mail-order firms like Sears were able to penetrate underserved rural areas by leaning on new infrastructure, such as the railroads that linked far-flung regions of the country. Government regulation also aided the company’s growth, with the Rural Free Delivery Act of 1896 underwriting its distribution chain by expanding mail routes in rural areas.

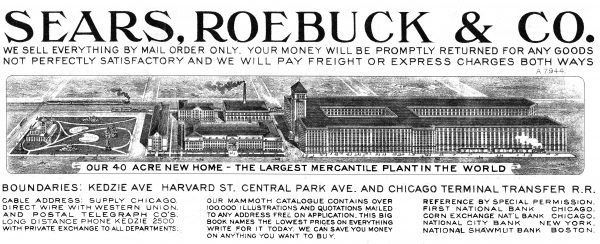

Sears, Roebuck letterhead from 1907 featured the mail-order company’s state-of-the-art distribution center, a symbol of its retail dominance. Image courtesy of Sears, Roebuck & Co/Wikimedia Commons.

In an era when print media reigned supreme, Sears dominated the rural retail market through its huge catalog, an amazing work of product advertising, consumer education, and corporate branding. Titled the Book of Bargains and later, The Great Price Maker, the famous Sears catalog expanded in the 1890s from featuring watches and jewelry to including everything from buggies and bicycles to sporting goods and sewing machines. It educated millions of shoppers about mail-order procedures, such as shipping, cash payment, substitutions and returns. It used simple and informal language and a warm, welcoming tone. “We solicit honest criticism more than orders,” the 1908 catalog stated, emphasizing customer satisfaction above all else. Sears taught Americans how to shop.

Sears also demonstrated how to run a business. Cutting costs and tightly controlling distribution fueled its rise to power. The company built a massive Chicago distribution complex in 1906, which occupied three million square feet of floor space. A full-page illustration of the plant, in all its bright redbrick glory, graced the back of the Sears catalog. Any customer could see how his merchandise was received and held, how his orders were filled and shipped out, and where the catalog itself was published. The distribution center was its own best advertisement; among the largest in the world, it was a symbol of the mail-order company’s dominance.

The company innovated in other ways, too. Bricks-and-mortar retailers today have to contend with new consumer habits brought about by e-commerce. Similarly, mail-order firms like Sears faced potential loss of their markets as the nation urbanized 100 years ago and entered the automobile age. Sears navigated the challenge brilliantly when it opened its first department store in Chicago in 1925. Under the managerial leadership of Gen. Robert E. Wood, who had formerly worked with mail-order competitor Montgomery Ward, Sears initiated a rapid expansion outside of urban centers. By 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression, it operated more than 300 department stores.

In 1948, Ruth Parrington, a librarian at the Chicago Public Library, studied a Sears catalog from 1902. Photo courtesy of Associated Press.

Growth continued even during the economic downturn, because Sears wisely championed an aesthetic of thrift. The chain made its name selling dependable staples such as socks and underwear and sheets and towels, rather than fashion items like those found in traditional department stores such as Marshall Field’s in Chicago or John Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia or New York. Sears outlets were spare, catering to customers who were interested in finding good value, to meet practical needs. By the end of the Depression decade, the number of stores had almost doubled.

After World War II, still under Wood’s leadership, Sears continued to open new stores across North America, in the bustling new shopping centers populating the expanding suburban landscape. In the United States, the number of Sears stores passed 700 by the mid-1950s. The firm also expanded across the borders north and south, opening its first Mexico City store in 1947 and moving into Canada in 1952 (incorporating with a Canadian mail-order firm to become Simpson-Sears). Sears benefited from being a pioneer chain in a landscape of largely independent department stores. Along with J.C. Penney, it became a standard shopping mall anchor. Together, the two chains, along with Montgomery Ward, captured 43 percent of all department store sales by 1975.

Sears wouldn’t really lose any footing until the 1970s, when new challenges emerged. Skyrocketing inflation meant low-price retailers such as Target, Kmart and Walmart, all founded in 1962, lured new customers. The market became bifurcated as prosperous upper-middle class shoppers turned to more luxurious traditional department stores, while bargain seekers found lower prices at the discounters than at Sears.

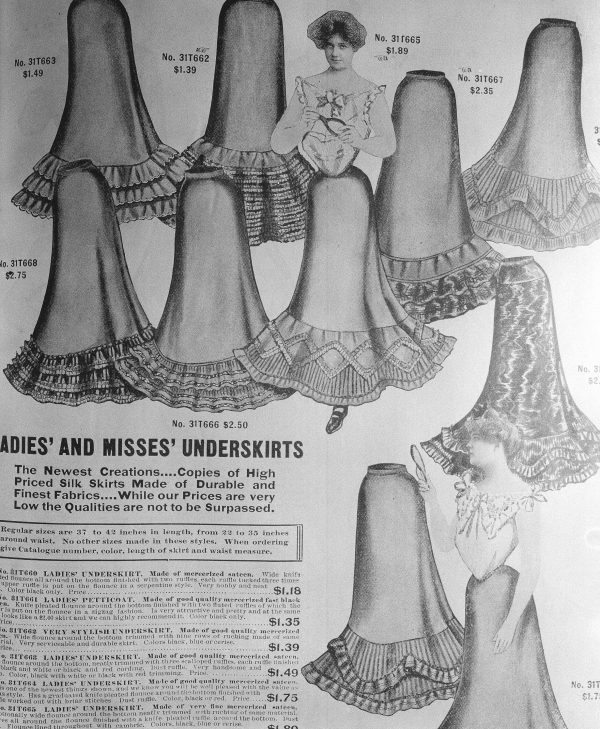

Women’s and girls’ underskirts featured in the 1902 Sears Roebuck catalog sold from $1.18. Image courtesy of Edward Kitch/Associated Press.

In 1991, Walmart overtook Sears as the nation’s largest retailer. As big box stores began to dominate the country, the department store industry responded through mergers, reorganization and experimentation with the department store category itself. Sears was no exception. The company took many different tacks under a series of problematic leaders, losing sight in the process of its traditional niche, which it ceded to discounters. Sears moved into insurance and financial services. Its credit card business, for example, accounted for 60 percent of its profits at the turn of the 21st century. In 2003, however, it tried returning to its retail core, selling its credit and financial business to Citigroup for $32 billion.

There is a tendency to look at Sears’s decline, and the potential loss of a grand icon of American business, with fond nostalgia. This would be a mistake. Sears embodied many of the uglier aspects of American capitalism, too. Many times, the firm’s management pushed back against forces that benefited workers. Sears tried to undermine organized labor, successfully resisting it even though several other traditional flagship department stores had unionized by the 1940s and 1950s. Company leaders resisted 20th-century progressive social movements that sought economic equality for African Americans and women. Like other department stores, Sears contributed both to structural and daily acts of racism, against customers and workers. African-American boycotts against Sears in the 1930s, for example, exposed racist hiring practices; in the late 1960s, welfare-rights activists revealed the firm’s discriminatory credit policies. Gender inequality was deeply entrenched in its work structure—and challenged, prominently and unsuccessfully, in the famous 1986 “Sears case,” which emerged from an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint concerning discrimination against women, who had been passed over for lucrative commissioned sales jobs in traditionally-male departments.

All of it, good and bad, reflects our nation’s struggle to adapt to larger economic, political, and cultural forces. For historians like myself, who see business as a social institution through which to view and critique the past, the end of Sears will mean more than just one less place to buy my socks.

Vicki Howard is a visiting fellow in the department of history at the University of Essex. The author of the award-winning From Main Street to Mall: The Rise and Fall of the American Department Store (Penn Press, 2015), she comments on American and UK retail on Twitter at @retailhistorian.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment