Debates rage today about the risks and benefits of modern technology. Driverless cars, the use of drones in warfare and commerce, the deployment of robots in place of human soldiers, surgery by robotic rather than human hands. The Internet of Things that puts digital devices in just about everything. Artificial intelligence not only assisting but superseding the human brain. Genetic manipulation of food, organisms, and human parts. Human cloning—even the manufacture of human beings.

The National Institutes of Health recently announced that it plans to end the ban on funding research for part-human, part-animal embryos, raising urgent ethical questions such as, what if this produces an animal with a partly human brain?

But the origins of these very modern concerns date back more than a century, with lively discussions about “modernization” underway as early as the Paris World’s Fair of 1900. One especially compelling yet largely forgotten analysis was penned by Henry Adams, son of a congressman and diplomat, descendant of two U.S. presidents, and a highly regarded historian—and conflicted technology enthusiast—in his own right. His reflections were contained in his posthumously published autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams.

In a chapter titled “The Dynamo and the Virgin,” he ponders the implications of the Machine Age, expressing deep concern over what he sees as a dangerous clash between the seductive grandeur of modern science and technology, which he calls “the Dynamo,” and the essential undergirdings of humanity—religion and traditional values—which he christens “the Virgin.”

More introspective than descriptive, The Education of Henry Adams was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1919. It leads the Modern Library’s list of the top 100 English-language nonfiction books of the 20th century, outranking Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.

Today, Adams’s work is not nearly as widely known as those, but not for lack of merit and timeliness. Indeed one could argue that “The Dynamo and the Virgin” is even more relevant today than it was when it was written.

After studying exhibitions on art, science, and technology at the Paris World’s Fair of 1900, Adams concluded that—despite his own appreciation of the merits of “progress”—Americans were too ready to embrace new technology at the cost of traditional values. This raised for him a disquieting question for the dawning century: Will the human spirit survive the new Age of the Machine?

Adams was anxious that American culture was about to take a fateful turn, sacrificing traditional values on the altar of technology. Prompting his reflections was a visit to the Hall of Electrical Machines. He fixated in particular on one of the gigantic dynamos on display. Its purpose was beside the point. Adams’s focus—and his fear—centered on its size and mechanism, its “huge wheel, revolving within arm’s-length at some vertiginous speed” while making hardly a sound. Its workings, he wrote, were an unfathomable, but seductive, mystery—one that left him in awe. The dynamo became for him the incarnation of modernity and symbol of the “revolution of 1900”—interwoven revolutions in science and technology that ushered in, most impressively, the new age of electricity along with automated production, the car, and the airplane.

And then there was the art. Adams contrasted the dynamo with the figure of the Virgin, which he suggested was the central inspiration behind much of what he had viewed in the fair’s acclaimed art pavilions. The Virgin became his symbol for Christian tradition and, equated by Adams to the Roman mythological Venus, the female force in general. Looking to the future, he wondered if the god of technology, the dynamo’s apotheosis, was on the verge of replacing, as he put it, the Church and the Cross. Adams was in fact seeking a middle ground between religion and science.

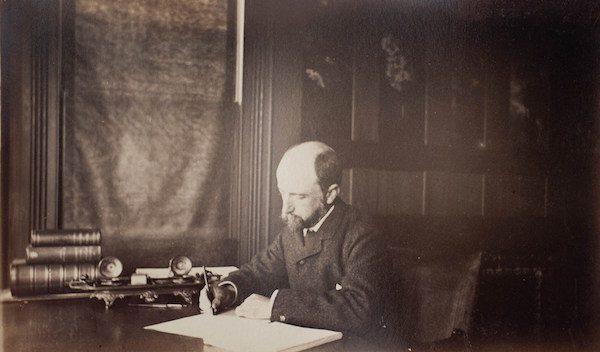

Henry Adams seated at his desk, 1883.

Adams’s guide through the Hall of Electrical Machines was a leading American scientist, S. P. Langley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Although holding Langley in the highest esteem, he wrote of being puzzled, and a bit disturbed, by the scientist’s laser-like focus on machines and forces, to the exclusion of the art displays and all else non-scientific at the fair: “Langley, with the ease of a great master of experiment, threw out of the field every exhibit that did not reveal a new application of force, and naturally threw out, to begin with, almost the whole art exhibit.”

Adams, writing in the third person about his experiences, described how Langley taught him to appreciate, if not really understand, recent discoveries in radioactivity, radio, and electricity: “He [Adams] wrapped himself in vibrations and rays which were new, and he would have hugged Marconi and Branly [inventor of the Branly coherer, one of the earliest radio wave detectors] had he met them, as he hugged the dynamo.”

Long fascinated by modern physics, Adams later experimented with applying physical theories, including the Second Law of Thermodynamics, Entropy, and “Maxwell’s Demon” (a thermodynamic thought-experiment by physicist James Clerk Maxwell), to the theory of human history, even in the face of skeptical feedback from scientist friends. But it was the dynamo that excited his strongest reactions at the Paris fair: “As he grew accustomed to the great gallery of machines, he began to feel the 40-foot dynamos as a moral force, much as the early Christians felt the Cross … Before the end, one began to pray to it.”

Indeed, Adams later did pray to it, composing a poetic tribute, “Prayer to the Dynamo: Mysterious Power! Gentle Friend! Despotic Master! Tireless Force!” he wrote, with more than a hint of ambivalence.

The rush of discoveries in science and technology sometimes left him longing for the solace of tradition, security, and unity that he associated with medieval society and the Church. That people now seemed to be turning away from the Virgin worried him, for he believed it could mean the end of the great artistic traditions that were propelled by the power of Christian faith, “the highest energy ever known to man,” surpassing even the power of the steam engine and the dynamo.

Adams noted that in Europe the “force of the Virgin was still felt at Lourdes, and seemed to be as potent as X-rays,” while “in America neither Venus nor Virgin ever had value as force.” Despite his personal religious skepticism, (he was attracted to religion, but remained agnostic, never really reconciling the truths of science and religious faith) he regretted that his countrymen were apparently throwing in their lot with the machine worshippers.

So, what does Adams have to say to us today as we confront the dilemmas of our own technological revolution? Adams was enthusiastic about modern science and technology—today we might refer to him as an early adopter—but he remained an essentially 19th-century man, mindful of the challenges to society posed by 20th-century technology. His hope was that dynamo and Virgin would ultimately join together in support of both our spiritual and material lives.

To be sure, we no longer speak of dynamos and Virgins, much less of “hugging dynamos.” Yet, in many ways, Adams was extraordinarily prescient. With today’s advances in artificial intelligences and genetic manipulation, we face the very existential crisis that Adams foresaw.

Precisely one hundred years after Adams’s toured the Paris Exposition of 1900, Bill Joy, co-founder and former Chief Scientist of Sun Microsystems, wrote his now famous essay in Wired magazine, “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,” projecting a dystopian future in which “our most powerful 21st-century technologies—robotics, genetic engineering, and nanotech—are threatening to make humans an endangered species.” Adams was not half so gloomy as Joy. From the vantage of the revolution of 1900, he welcomed our technological future, but with a crucial caveat: make sure our technology has a soul, not in the sense of superseding us as sentient human beings, but of living in spiritual harmony with our better selves.

is director emeritus of the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center at the National Museum of American History.

Primary Editor: Sara Catania. Secondary Editor: Andrés Martinez.

*Lead image courtesy of Library of Congress. Interior photo by Marian Hooper Adams/Wikimedia Commons.

Add a Comment