In 1822 the Austrian emperor Franz I and his ally Tsar Alexander I of Russia held a meeting in a remote valley of the war-torn Tyrolese Alps. They were entertained by the Rainers, a locally renowned family of singing farmers. When the visiting dignitaries heard the improvisational simplicity of the family’s performance of native Alpine songs, they encouraged the four Rainer brothers and their sister to leave the war behind and take their homegrown mountain show on the road.

The Rainers performed their rustic harmonies across Europe and eventually America, inspiring many imitators in their wake. But no one could have foreseen how these Alpine yodelers would help transform the racist entertainment of blackface into a respectable middle-class pastime in a way that still persists in American art and politics.

In 1827, when the Rainers reached Britain, minstrels were all the rage. (Think zombies today, from Jane Austen parodies to The Walking Dead, iZombie, and Z Nation.) Such poet-musicians, who glorified famous heroes and told chilling folk tales, who piped troops into battle and sang at firesides, had all but died out after Queen Elizabeth outlawed them as “sturdy beggars” in 1597. But 150 years later British poets revived the idea of the minstrel. Thomas Gray is credited with kicking it all off in his 1757 poem, “The Bard,” about a medieval Welsh minstrel who single-handedly stares down the entire English army, foretells the glory of the Tudor dynasty, and then leaps to his death from atop Mount Snowdon. Other poets soon followed suit with a new kind of minstrel who reminded Britons of their natural and heroic roots.

In their folk costumes and feathered caps, the Rainers were an overnight success in London, where they were seen as the living embodiment of the minstrel craze, and immediately dubbed the “Tyrolese Minstrels.” Using everything from spoons and kazoos to guitars, fiddles, and bugles, they played waltzes, Ländler, and other traditional Austrian and Swiss folk dances. And just like the minstrels fashioned by Gray and others, they were informal, unaffected, and moving, the voice of refugees seeking freedom while preserving the culture of their homeland.

As they brought the minstrel back to life, the Rainers changed that solitary Romantic figure into an ensemble. They were famous for the way they seamlessly blended their harmonies. Ear-witnesses often commented on the “unity” with which these siblings wound their vocal lines into a single, finely spun thread of sound. We usually think of harmony as organized vertically, a stratified sonic society where each voice has its role to play and never gets above itself. But the Rainers seemed to make harmony horizontal.

This pure and simple sound proved irresistible to American ears when the Rainers arrived here in 1834. Attendance at their imported folk concerts became not just a matter of musical taste but morality. At the time, Americans were caught up in a middle-class fashion for self-improvement. The Rainers, and the many European “minstrel” family singers who followed them, morphed from symbols of lost culture into cultural capital. Being seen at concerts and knowing the songs marked one as au courant.

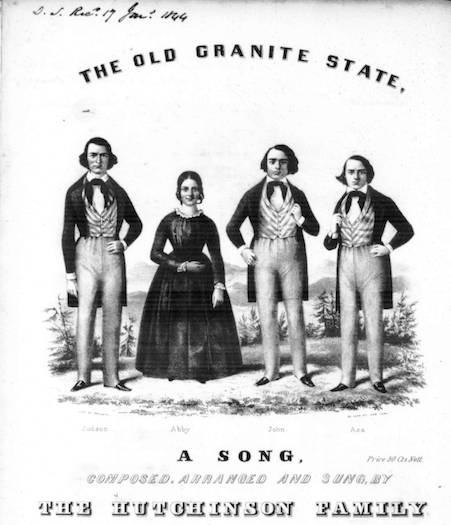

Figure 2: The Granite State Minstrels. Courtesy Library of Congress, Music Division.

Soon Yankee audiences, invigorated by a new spirit of nationalism and a desire to find a uniquely American identity, longed to hear from minstrels native to their own shores. A domestic minstrel market opened up. Enter the Hutchinsons.

Like the Rainers, the Hutchinsons were farmers and their New Hampshire roots became their identity when they began touring in 1840 as the Granite State Minstrels. And like the Rainers they sung simple, close harmonies with well-blended voices. (Consider the sound that became the barbershop quartet.) But by joining that sound to hot topics like temperance and abolition, the Hutchinsons made such harmonies seem particularly American. Weaving one voice out of many, they created the musical equivalent of E pluribus unum. They sang the body politic. And the sound was democracy, the dream that every note, like every vote, counted.

This new democratic sound thrived as more American minstrel groups adopted it, but the politics of race and the economics of entertainment quickly intruded. These family-friendly folk minstrels packed the respectable concert halls of northern cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. But across town, in the poorer, mixed-race, immigrant neighborhoods of these same cities, districts like New York’s Bowery, another kind of entertainment had become popular.

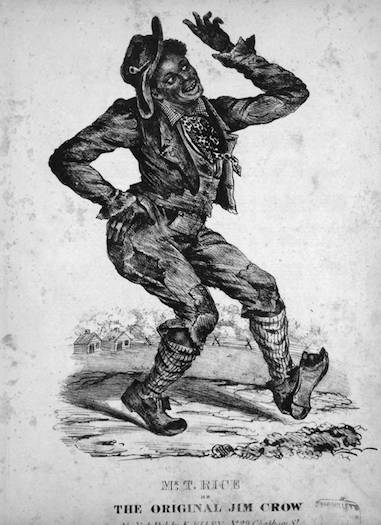

Figure 3: Thomas Dartmouth Rice as Jim Crow. Courtesy Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, Special Collections, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

In the 1830s early blackface performers, known mostly as “Ethiopian delineators,” created raucous theatrical extravaganzas that parodied middle-class dress, manners, and desire for upward mobility. Ridiculous farces and what were then known as “Ethiopian operas,” with names like The Virginia Mummy and Bone Squash Diavolo, made fun of both white authority at the top and poor blacks (free and slave) at the bottom. As historian Eric Lott describes in his book Love and Theft, audiences for these performances were mostly working-class young men, both white and black, and this theater encouraged a kind of class solidarity among a disenfranchised audience eager to make itself feel better by watching African-American stereotypes hoist the middle classes on their own petard.

With the exception of a few superstars (like Thomas Dartmouth Rice, pictured above as his most famous character, Jim Crow), blackface was neither socially acceptable nor particularly lucrative.

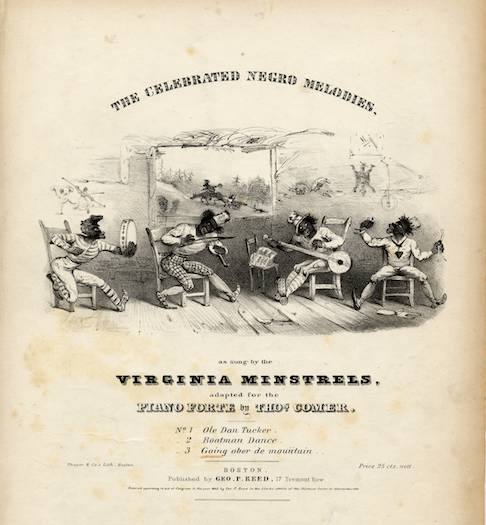

That all changed when blackface delineators saw the potential for cash and cultural cache in imitating folk-singing families like the Rainers and the Hutchinsons. In 1843 Dan Emmett, former circus clown and future composer of the Confederate national anthem “Dixie,” cobbled together some cronies in his Bowery boarding house to create the Virginia Minstrels, the first blackface band in history to use the moniker “minstrel.”

Figure 4: The Virginia Minstrels. Courtesy John Hay Library, African American Sheet Music Collection, Brown University.

To suit their newer, more cultured title, blackface minstrels changed not only in form but formality. They promised performances purged of the “vulgarities” that had previously characterized blackface. By the 1840s, playbills and advertisements pledged “chaste” entertainments to attract their target audiences of white women and children as well as respectable family men.

In this context “chaste” meant whitewashing the more risqué, sexually explicit content that previously defined blackface performance. But it also meant a change in singing style. The newly renamed minstrels adopted the same horizontal harmonizing the Hutchinsons and other American minstrels had borrowed from European minstrels. In harmonized versions of songs like “The Fine Old Color’d Gentleman” and “Old Uncle Ned,” musical simplicity was made to sound like moral chastity in spite of the overt racism that characterized the whole genre.

This rebranding of vulgar delineator as chaste minstrel was a resounding success. The blackface minstrel show became the most popular entertainment in 19th-century America.

And yet, as the middle classes shifted from being the object of blackface mockery to blackface’s target audience, minstrel humor turned explicitly hateful and malevolent. In short, blackface minstrels used what Frederick Douglass called the Hutchinsons’ “soul-enlarging and heart-melting melody” to “pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens.”

Today, blackface’s bid for respectability is mostly forgotten, but the ghost of the minstrel still stalks the American stage. Alison Kinney has written about the only recently discontinued practice of blackface in the Metropolitan Opera’s performances of Verdi’s Otello.

co-authored this piece. Daniel H. Foster is a Senior Lecturer in Drama at the University of East Anglia and currently at work on a book about minstrels. Anne Bramley is an independent scholar whose work has appeared at NPR and The Washington Post.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli. Secondary Editor: Sara Catania.

*Lead image: The Tyrolese Minstrels. Courtesy Library of Congress, Music Division.

Add a Comment