How Andrew Carnegie’s Genius and Blue-Collar Grit Made Pittsburgh the Steel City

A Third-Generation Mill Worker Pays Homage to the Controversial Industrialist

Teeming a crucible of steel at the Colonial Steel Company, Pittsburgh in 1912. Photo courtesy of Colonial Steel Collection, University of Pittsburgh, Archives Service Center.

I’m a retired steelworker—third generation at the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. on the south side of Pittsburgh. Both of my grandfathers were steelworkers, and my father was a first helper, meaning he was in charge of one of the steelmaking furnaces in the plant. When my father was ill and dying and on a lot of pain medication, he would mystify doctors with certain motions he would make with his hands and arms. But I knew right away that he was making steel—opening furnace doors and adjusting the gas on the furnace and the draft. To the day he died, he lived steelmaking.

My life is steelmaking too—I worked as a laborer, a supervisor, and a manager for over 40 years. I’m also a devoted student of the history of steel, an interest that was spurred by my family story and my work, and then fueled by my deep desire to answer a single question: How was it that in the latter half of the 19th century it was Pittsburgh—not Chicago or any number of well-positioned metal-making centers in the U.S. and Europe—that somehow became the world’s largest steel manufacturing center?

Pittsburgh’s ascent is often attributed to the region’s vast coal supply, extensive river system, and burgeoning railroad network. Of course, these are factors, but I wasn’t convinced that they were reason enough. Numerous cities in America and Europe had similar attributes, and manufacturing regions in England had the added advantage of originating modern mass-produced steelmaking. So what brought Pittsburgh to the forefront?

The author’s grandfather, Vid Salopek (far left) and grandmother, Amanda (Vucic) Salopek,

both immigrants from Croatia (Yugoslavia). Vid worked for the Carnegie Steel Company. Photo courtesy of Ken Kobus.

The answer, in my opinion, primarily revolves around the actions of one man, Andrew Carnegie, and his singular ability to marshal the forces of science, technology, and innovation to consistently make his plants the most efficient and advanced in the world. Many choose to believe that Carnegie’s fortune was won through his abusing of employees and cutting their wages to the bone. Initially I, too, assumed this was true. But years of study and research were full of surprises, which led me to write a book on the subject, and to a very different conclusion.

In addition to writing, I’ve taught at Carnegie Mellon University’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. In one of those classes I focused on the infamous Homestead Strike of 1892, in which the trade union workers of Homestead Steel Works faced off against the Carnegie Steel Company in a wage and policy dispute. It ended badly—nine people were killed. So it might surprise you to learn that I presented the material from the perspective of the Carnegie Steel Company.

In my experience, I’ve found that most people despise Carnegie. I’m not saying he didn’t do his share of things that many consider ruthless or immoral—he pushed long hours and low wages—but they don’t understand who he was or his incredible life and contributions. Carnegie was born in Scotland, the son of a weaver whose family was driven into poverty when the mechanization of looms made hand-weaving obsolete. After immigrating to the U.S., the young Andy worked as a bobbin boy in a textile mill, as a telegraph messenger, and as a telegrapher, eventually working his way up through the Pennsylvania Railroad to Pittsburgh Division Manager before turning his attention to steel. He assembled his steelmaking empire around three smallish integrated plants, located on several hundred acres of land, distributed over approximately a five-river-mile length of suburban Pittsburgh. Their combined output often rivaled or exceeded that of the world’s major steelmaking nations, including that of England and the rest of the United States.

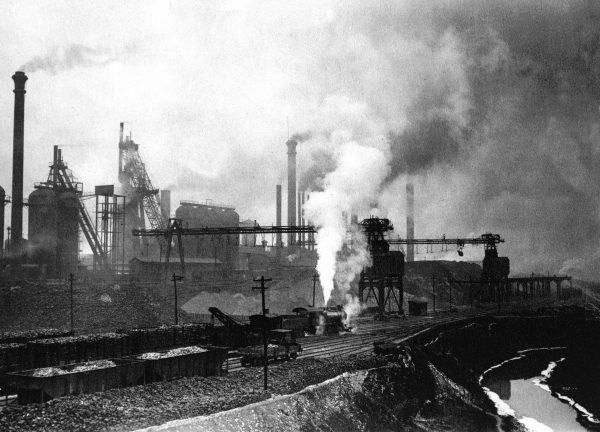

Duquesne Works of Carnegie Steel Co., circa 1901. Photo courtesy of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

The mill has a certain music. I grew up in the shadow of Carnegie’s mills and have sensory memories starting from when I was a small child. Back when they were steam-driven you could hear the rhythmic chug, chug, chug of the mill engines and the hiss of the steam releasing. Also the boom and the clang of metal and chains, the whirling of gears and motors, the dull thud of striking a humongous red hot ingot, and the warning sounds of sirens. There were the odors too—if you’ve ever heated a metal pan with nothing in it, that’s the smell. And all day every day there were fireworks throughout the mill. When charging molten iron in through the open door of a furnace it’s like the Fourth of July, with thousands and thousands of sparklers flying, quite spectacular. There may be 40 tons of seething liquid iron in the ladle and 300 tons in the furnace. Some modern plants were miles long; mine was one of those. I would feel like a peewee ant in this gargantuan surrounding. It was awe-inspiring.

Sometimes the things that went into creating that spectacle and improving upon its efficiencies were quite modest—the Carnegie Company often made simple adjustments to the routine, such as adding a chemist on the shop floor. In modern analyses of the industry, small changes like this are often overlooked, but these departures from conventional practices often enhanced links or forged new ones among the three fundamental approaches to making steel: ironmaking in a blast furnace and steelmaking via either a Bessemer converter or an open hearth furnace.

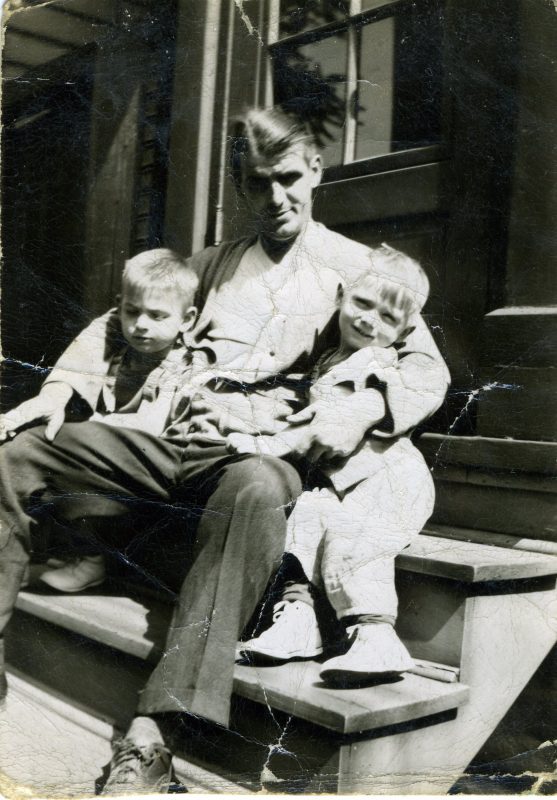

The author’s father, John, and two older brothers, Regis and Jerry, in 1945. John worked as a first helper on open hearth steel furnaces at Jones & Laughlin Steel Company Pittsburgh Works starting in 1937. Photo courtesy of Ken Kobus.

In the production of iron with the blast furnace, a business that Carnegie entered in 1872, his men reinvented the industry three times in three consecutive decades. Important changes included chemical analysis and adjustments to air flow volume and temperature, as well as installing more efficient stoves, construction materials, and high-quality blowing machinery. These sorts of changes, coupled with automation, increased production many times over. It was during that time that ironmaking was first recognized as a science, a change attributed by industry experts to the work at Carnegie Steel.

Another important contributor to Carnegie’s success were the men who helped him run the business. Carnegie’s partner, Henry Frick, was perhaps the finest executive manager in the world. Bill Jones, a preeminent steel man and inventor known as Captain Jones, helped elevate the company to record levels of both iron and steel production. Among his numerous patents was the mixer, which eliminated two steps in the steelmaking process. He developed an esprit de corps among the workers, partly by convincing Carnegie to introduce the three-turn, eight-hour day in the late 1870s (though the company reverted to a two-turn, 12-hour day in 1888).

If Carnegie’s unrivaled inventiveness and driving ambition were essential to Pittsburgh’s rise, so was the sense of pride in sweaty, back-breaking labor that inspired the steelworkers themselves, including my relatives. When I think about Jones I am reminded of the American folk heroes of my childhood like John Henry, the “steel driving man.” There was also Mike Fink, a hero of local folklore who ran boats down the Ohio River to New Orleans and was known as the king of the keelboaters. And also Joe Magarac, a man who—I was told as a young child—was literally made of steel. Here’s this mythic figure and all he cares about is making steel—the strongest of the strong, a man to be emulated. But in Eastern European languages, magarac means donkey. People would laugh at him. Yet he’s a hero because he loved making steel. This local steelmaking lore, however romanticized, is another thing that made Pittsburgh stand apart from its rivals.

When I started out, I was in the strip mill—a laborer with a shovel. Then I got married and moved to the coke plant, where it’s easy to get a job because it’s very dirty work. But it was steady, and I worked in one for the rest of my career. When I was 26 I started studying mechanical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh and working swing shifts. It was during the course of my studies, as I was reading about steel and the history of the industry, that I learned that Pittsburgh was not the most natural place to be the center.

One of the things I discovered was Carnegie’s brilliance in the utilization of scrap. Bessemer steel plants generated large volumes of scrap, but Bessemer furnaces generally could not or did not use scrap for a number of different reasons. In economic terms, this commodity had a value, but little utility; it lacked usefulness. Carnegie changed that.

Charging a Bessemer Convertor with approximately five to 10 tons of molten iron prior to

conversion to steel. Presumably Pittsburgh, PA, circa late 19th century. Photo courtesy of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

He approached basic steelmaking through the use of open-hearth furnaces, which used scrap metal and pig iron, also called cast iron, to make steel. An acid open hearth required the use of very high-quality scrap, which made its operation expensive. When Carnegie developed the capability to produce basic steel in open-hearth furnaces, he was able to use lower-quality scraps that were contaminated with phosphorus, so it was cheaper to make.

Carnegie could use this material in basic furnaces and convert it into steel—he was the first in the United States to do this. Carnegie owned two of the most productive Bessemer plants in the world, so in essence he could get the scrap for free. Not only that, he used it to make armor plate, boiler plate for locomotives and steel beams. He now had a plant, unique in the country, where he could take large volumes of low-utility scrap or even purchase it from others at low cost, and make high-value products that had high utility. That was one of Carnegie’s big breakthroughs, an important one that helped secure Pittsburgh’s place as the steel capital.

During this era, America was changing from an agrarian to an industrial society. The steel industry—and Carnegie himself—played a major part in that transformation. Propelled by Carnegie’s impetus, the United States became the largest iron-producing nation in the world. Shortly after his exit from business in 1901, it surpassed England as the largest steel-producing nation as well. With steel affordable and in ample supply, railroads could be rapidly constructed across America’s vast expanses and skyscrapers could reach toward the heavens. Later, a number of other new steel plants were established in the Pittsburgh region, solidifying the city’s position as the major steel center in the world.

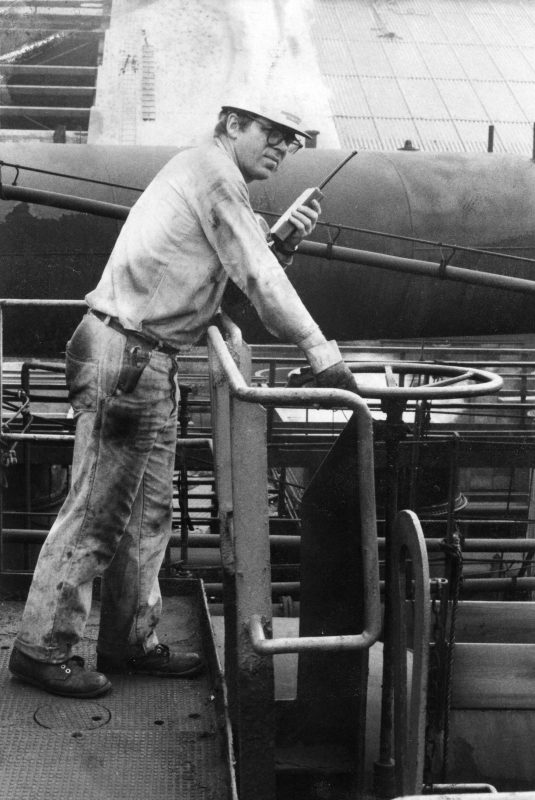

The author at work adjusting the pressure on a unit of coke ovens, Pittsburgh Works Jones & Laughlin Steel Company. Photo courtesy of Ken Kobus.

Carnegie’s wealth is well known. However, what is not so well known or understood, and worth noting, is that Carnegie did not amass his great fortune until after he sold his company to J.P. Morgan in 1901 for $480 million—by some estimates about $13 billion in today’s money.

Then he gave almost all of his share away—today, there are no wealthy Carnegies. The list of beneficiaries of his philanthropy is long, and includes, among many others, the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute of Technology—now Carnegie Mellon University—Carnegie Institution of Washington (Science), and the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the largest endowment for advancement of education and knowledge.

The hardest work I have ever done was being a third helper on an electric furnace. It was hand charged, the hottest heat, and the hardest work. Your clothes would get soaking wet. The sweat would run into your shoes, so you’d be squishing around in your own sweat. You simply work until you’re spent, sometimes until you feel you can’t move. So it was primarily Carnegie and his genius managers who made Pittsburgh the steel capital, but it was the men in the mills who made his awesome accomplishment possible—an accomplishment later perpetuated by my grandfathers, my father, and so many others.

Ken Kobus is a retired mechanical engineer who spent his entire working career at the Jones & Laughlin, LTV, and United States Steel companies. Besides his interest in steelmaking he has found a lifelong pleasure studying astronomy and the history of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He has written five books, including City of Steel.

Primary Editor: Sara Catania. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment