How Irish American Athletes Slugged Their Way to Respectability

Sportsmen with Roots in the Emerald Isle Reshaped the Image of the Shantytown Ruffian

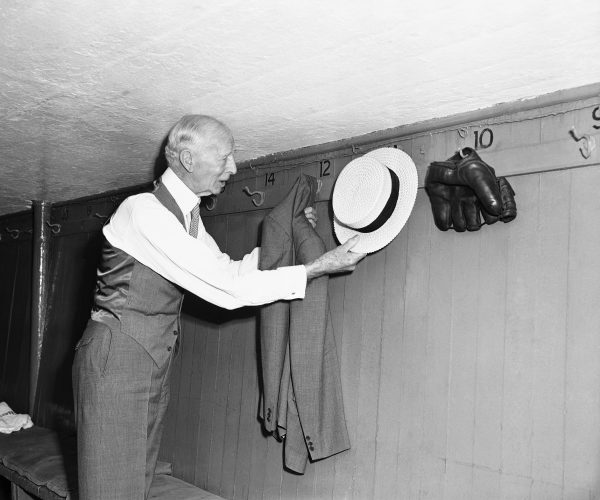

In 1949, 86-year-old baseball legend Connie Mack was honored in front of 65,000 fans at Yankee Stadium. The Philadelphia Athletics manager, known for his upright and gentle character, helped pave the way for an emerging Irish American establishment. Photo by Jacob Harris/Associated Press.

In his 1888 book The Ethics of Boxing and Manly Sport, a high-minded treatise on the ennobling effect of sports, the journalist, poet, and Irish exile John Boyle O’Reilly wrote that “there is no branch of athletics in which Irishmen, or the sons of Irishmen, do not hold first place in all the world.” The boast was closer to true than many would realize. By the turn of the 20th century, America’s professional sports were bursting at the seams with Irish athletes. And for all its bombast, O’Reilly’s lofty embrace of their athleticism bespoke a genuine concern about the image of his fellow Irish Americans.

The very idea behind O’Reilly’s book was ironic, even farcical. He was the most respected Irishman in Boston, one who dined with the Brahmins; he embodied Irish-American gentility and social aspirations. Yet his choice of subject—boxing—played into all of the worst fears about the Irish in his day, who were thought to be intemperate, uncouth, corrupt, and violent.

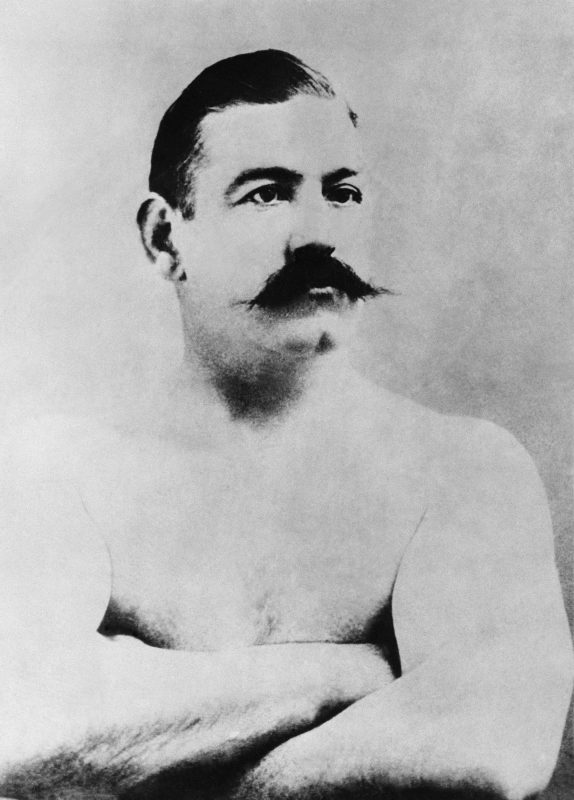

Boxing’s most prominent champion, the great John L. Sullivan, earned and squandered several fortunes, drank champagne by the bucket, left his wife in order to live openly with a chorus girl, and generally served as a walking affront to Victorian morality. That such a man could be the subject of several chapters in O’Reilly’s book displays a deep conflict in the Irish-American experience at the time—the emergent “lace curtain Irish” succeeding the so called “shanty Irish.” Stereotypes aside, the clashing identities were, for millions of Irish Americans, a very real struggle for redefinition.

John L. Sullivan, heavyweight boxer and unrepentant tough guy, in an undated photo. Photo courtesy of Associated Press.

Fifty years earlier, the Great Famine had spurred a massive out-migration of emigrants from Ireland, a wave so large it would be comparable to 13 million indigent newcomers arriving in the U.S. today. Most were dirty, unskilled, illiterate, and subject to exploitations we can barely imagine. But by century’s end, the Irish had taken over urban politics, turned the Roman Catholic Church into the nation’s largest denomination, and begun sending their sons and daughters to college.

It’s an old American story: The outsider becomes the insider, the country bumpkin becomes a sophisticate. For the Irish, the story often played out in the world of professional sports. Then as now, celebrities used autobiographies (sometimes clearly ghost-written) to polish and to reinforce their image; it was one of the perks of showmanship. Three such books by Irish athletes open a window on this transitional era and the push for respectability: John L. Sullivan, the last bareknuckle boxing champion; boxer James J. Corbett, widely known as “Gentleman Jim,” who straddled both sides of the social gulf; and baseball’s Connie Mack (real name Cornelius McGillicuddy), who raised respectability to an art form. All three, through carefully constructed public personae, promoted a virtual cult of respectability. Its cornerstones were sobriety, pious Catholicism, a home life focusing on idealized motherhood, and a preoccupation with good appearances.

Most professional athletes of the day fell well short of the cult’s standards, not least Sullivan, whose signature saloon entry involved striking the bar and bellowing, “My name is John L. Sullivan and I can lick any sonofabitch in the house!” It was a telling slur. To call someone an SOB is to slander their origins. Though he may have had a funny way of showing it, Sullivan, like any upwardly mobile Irishman of his day, cared about his breeding and his good reputation.

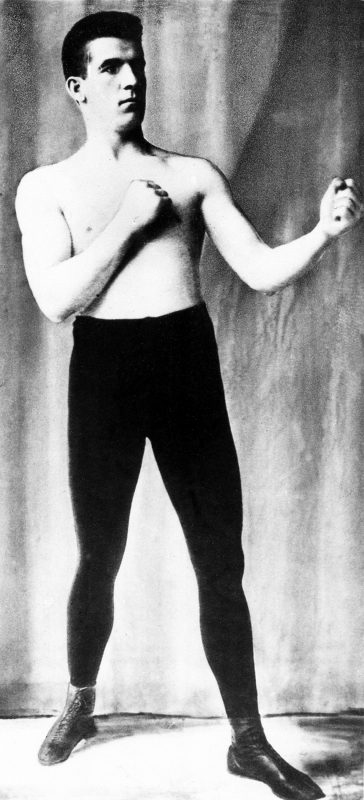

Boxer James Corbett, photographed in the 1890s, championed “scientific boxing,” a departure from the bare-knuckled brawls of the past, and attended the opera. His mother, who he revered, had hoped he would become a priest. Photo courtesy of Associated Press.

“My father and mother were Irish,” he would write in his 1892 autobiography, Life and Reminiscences of a 19th-Century Gladiator, “and I always aim at upholding the honor of the Irish people, who are a brave race.” His memoir was an attempt to disown his raffish side. He intended to show, he wrote, that he was “conscious of being something more than a pugilist.” He insisted that he could “give an intelligent opinion on almost any subject, and conduct myself as a gentleman in any company.” Sullivan proudly quoted a sportswriter who had remarked that, “He was a very well-read man, and preferred any time to discuss Shakespeare, Gladstone or Parnell to talking fight.”

Skepticism can be forgiven. In fact, when a publisher spotted his Life and Reminiscences in the public domain and reissued it, the memoir was retitled I Can Lick Any Sonofabitch in the House—a celebration of loutishness. That the same book could appear under two titles, one evoking classic courage and the other hooliganism is, in a way, the point: Sullivan knew that certain behaviors were unacceptable, but he also delighted in his own transgressiveness. His public delighted in it, too.

Sullivan was a ruffian who could pretend sophistication. But boxing has long tried to meld coarseness with refinement (as ringside fans and announcers in tuxedoes show), and it was “Gentleman Jim” Corbett who tipped the balance. Only eight years younger than John L., he truly was a polished young man. He read widely and attended the opera. As the literary critic John V. Kelleher said, Corbett “was a prophetic figure: slim, deft, witty, looking like a proto-Ivy Leaguer with his pompadour, his fresh intelligent face, his well-cut young man’s clothes. He was, as it were, the paradigm of all those young Irish Americans about to make the grade.”

Corbett was still a boxer, of course, but his 1925 memoir The Roar of the Crowd emphasized “scientific” boxing as a pointed renunciation of the old lumbering brawn of Sullivan’s generation. His memoir also took direct aim at Sullivan’s behavior outside the ring, recounting a time when Corbett witnessed the older boxer’s brash barroom insults first hand. In this telling, Corbett, a teetotaler, stepped up to give Sullivan a stern lesson in manners, telling him that profanity-laced namecalling was “hardly courteous, and I don’t want you to make that remark in my presence again!’” The rough-edged champ, we are told, “listens to reason.”

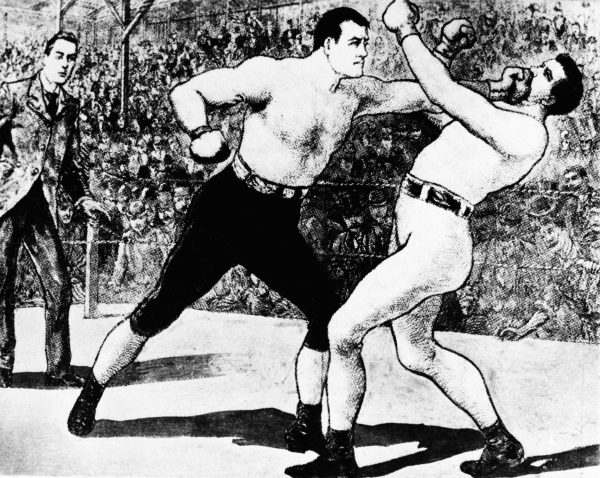

John L. Sullivan and James Corbett squared off in the ring in 1892. Corbett won, signaling the rise of a new, more respectable Irish American athletic icon. Image courtesy of Associated Press.

The Roar of the Crowd repeatedly asserts Corbett’s lifelong dedication to his parents. As champion, he pays off their mortgage, and late in the book he delights in taking his mother back to Ireland. Corbett’s account presents his father as deeply divided when it came to boxing, simultaneously ill-at-ease with it and proud of his son’s success. It should surprise no one that Corbett’s mother’s dream was for him to become a priest.

Corbett’s relative wholesomeness marked a symbolic step, yet when he wrested the boxing title from Sullivan in 1892, the Irish American community felt a pang of remorse for the old raffishness. It would be up to a baseball player to mark the decorous end of the shanty Irish world.

Though early baseball is not generally considered the Irish specialty that prizefighting was, at the end of the 19th century around 40 percent of professional baseball players were the sons of Irish immigrants, and the national game shared many of the concerns, and aspirations, of the American Irish. Ballplayers were known for gambling, liquor, brawling, and venereal disease, and baseball grew desperate to cast off its unsavory reputation. The American League was founded in 1901 as a conscious attempt to present a more sanitized and socially acceptable pastime. A founding paragon of its new respectability was another Irish athlete: Connie Mack.

The ever-formal Connie Mack hung up his hat and coat in the dugout at Yankee Stadium on August 10, 1950. Photo by Murray Becker/Associated Press.

He bore no traces of the hardscrabble mill town in which he’d grown up. Corbett may have been a gentleman, but Mack was a young man of exceptionally clean habits. When he got his first offer to play professionally, in the Connecticut State League, he did what any good Irish boy would do—he asked his mother for advice. Here is their reported exchange, from Mack’s 1950 memoir, My Sixty-Six Years in the Big Leagues: “‘Promise me one thing,’ she said. ‘Promise me that you won’t let them get you into bad habits. I’ve brought you up to be a good boy. Promise me that you won’t drink.’ I promised her, and that promise I shall keep to the end of my life.”

Indeed, in later years Mack, by then the venerable manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, unfailingly presented the game in terms of personal conduct, advising rookies that they must “have good moral habits and self-control. You can have everything else that’s needed to make the grade, but if you don’t have good moral character you are not for the big leagues.” Wilfrid Sheed once quipped that not swearing counts as the “pinnacle of virtue in baseball.” Mack’s disdain for rough language was famous. For a baseball man, he was heroically circumspect, rarely arguing a call. As a manager, he always wore a suit and starched collar, which kept him off the field and out of the public eye.

Personal reserve, and humility—concepts foreign to Sullivan and Corbett, who thrived on their superstar status —were cherished aspects of his public face. So unobtrusive was Mack that when a holiday was declared in Philadelphia after the 1910 World Series, he reportedly rode a public streetcar to the mayor’s office and went unrecognized. Mack’s formal persona would eventually eclipse, or even excuse, his baseball. He came to be honored for his rectitude rather than his team’s achievements. By the time of Mack’s eventual retirement in 1950, the old rough-and-tumble Irish America that had produced these athletes was all but forgotten. In another decade, the Harvard-educated Kennedys would be playing touch football on the White House lawn.

James Silas Rogers is the author of Irish-American Autobiography: The Divided Hearts of Athletes, Priests, Pilgrims and More (Catholic University Of America Press, 2016).

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment