The ’70s Pop Idol Who Was a ‘Safe’ Sex Symbol for Girls

The Partridge Family's David Cassidy Had an Androgynous Sweetness That Made Him Part Older Brother, Part Girlfriend

David Cassidy at The Plaza Hotel, New York, 1972. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

When David Cassidy died, aged 67, in November 2017, reports in the press suggested that legions of middle-aged women were plunged into mourning. Cassidy, whose career was kick-started with the role of Keith Partridge in the 1970s musical-sitcom The Partridge Family, enjoyed explosive success during that decade as a singer, songwriter, and musician, but most sensationally, as the love interest of swathes of adoring teenage girls across North America, Europe, and many other parts of the world.

These days we are fairly knowledgeable about fangirls and fandom and male pop idols, from Elvis and the Beatles to Justin Bieber, but Cassidy’s stardom was surprising at the time—not only for the size of his fan club, but also for the nature of his appeal.

History reminds us that although the phenomenon of females going wild over male musicians was not new—after all, 19th-century women had swooned in their droves over Franz Liszt’s piano playing—20th-century conditions made for differences in experience and scale.

In the 1950s, for example, the career of young musician and rock and roll star Ricky Nelson hinted at what was coming. Ricky Nelson’s fan mail was said to fill an entire room in the Hollywood post office, and his family was allegedly driven to construct an electric fence around their home to keep out love-crazed female intruders. Life magazine ran a cover story on Nelson, coining the term “teenage Idol.”

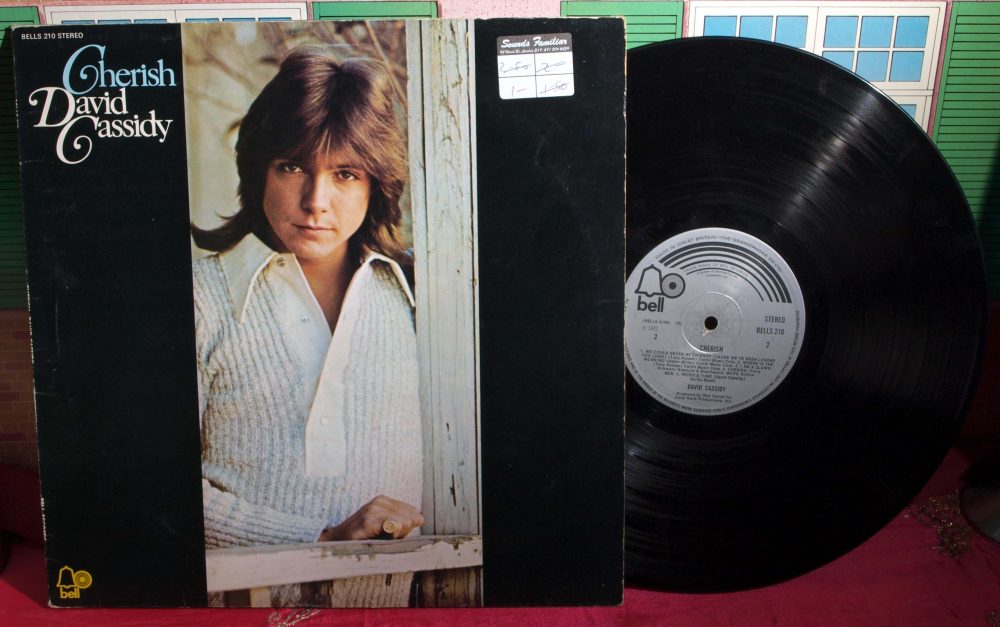

There was money in all this, but it wasn’t easy for a new breed of music managers to get the formula right and to predict what—or who—young girls would go for. When, in the 1970s, a tidal wave of youthful female passion built up round David Cassidy, threatening to engulf him altogether, he himself was astonished, and many observers, particularly men, were gobsmacked. To many of them, Cassidy looked like a girly boy, with his Bambi-like innocence and his penchant for knitted tank-tops worn over flowery cheesecloth shirts. Cassidy was smooth-chinned, and looked like he didn’t need to shave. Cassidy was pretty. Although he briefly experimented with an edgier, bad-boy image in his 1972 solo album Rock Me Baby, he soon reverted to sweet, baby-faced form.

‘Bambi-like’ innocence: teen heartthrob David Cassidy in his 1970s heyday. Photo courtesy of Flickr.

And it was his peculiar quality of sweetness, bordering on androgyny, which underlay much of his appeal. Cassidy was nice. He felt safe. Teenage girls stuck up posters and built shrines to him in their bedrooms. They diligently studied his tastes, researched his preferences, and tried to discover what his favorite colors were. He was almost one of them.

Many observers commented on this: how girls on the verge of discovering their own sexual feelings could feel unease about men who seemed too other, too powerfully different, and thus threatening. Cassidy was not alone in having a kind of reassuring charm. Musician Viv Albertine of the British punk-pop group The Slits, for instance, reminisced in a recent memoir about how in her youth she had nurtured a strong passion for Marc Bolan of T. Rex on account of his androgynous appeal. Whereas a musician such as Jimi Hendrix seemed too masculine, too overtly sexual, Marc seemed pretty and safe. “He wasn’t the kind of guy who would jump on you or hurt you.” Indeed “Marc was almost a girl.” And if, as a teenage girl, one feared a loss of control, it was still safer to let go of nascent sexual feelings in an environment with other fans, rather than with a real boyfriend.

Many women have since confessed that they once fantasized about how, if they could only put enough effort into trying to understand Cassidy, he would choose them as his sweetheart. This conviction often bordered on obsession—a kind of psychic voyeurism. The idea of a “special relationship” was encouraged further by the carefully designed, industrial production of Cassidy-themed memorabilia of the day, including a white fluffy teddy bear, with a red satin bow and “I think I love you” (the title of a Partridge Family No. 1 hit single) emblazoned on its vest.

The marketing of male heartthrobs had been standard practice since Colonel Parker had famously worked to turn Elvis into a brand name in the 1950s, licensing the production of all manner of memorabilia: charm bracelets, lipsticks, and plastic guitars. Teenage bedrooms silted up with Cassidy-themed merchandise in the 1970s. And the very titles of Cassidy’s hits both encapsulated and distilled the ache of youthful desires and passion, the terrible uncertainty about teenage romance, and trust: “Could It Be Forever,” “How Can I be Sure.”

A 1971 lunchbox bearing The Partridge Family, the band and TV show in which David Cassidy starred. Image courtesy of the Division of Culture and the Arts, Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

In fact, Cassidy’s sweet indecision showed how much women’s heartthrobs had changed through the 20th century. In the 1920s, it had been the smooth and masterful charms of Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik (1921) which had young women weak-kneed with passion. Even Elvis had tried to draw on Valentino’s potent legacy of “Oriental” exoticism. In the film Harum Scarum (1965) for instance, Elvis swashbuckles his way around “Babelstan” wearing a burnoose, his sideburns slicked into kiss-curls under various styles of keffiyeh or a turban. Hollywood endlessly recycled the sheiks, cowboys, pirates, and buccaneers who proved enduringly popular with women. But the teenage revolution and particularly, the purchasing power of young female consumers, helped to reconfigure the landscape of desire.

David Cassidy didn’t find it easy to be the object of mass adulation, especially when fan behavior ran amok. His concerts attracted the massive audiences (reputedly some 56,000 at the Houston Astrodome in Texas in 1972) which gave organizers terrible headaches and generated epic problems of security and social and civic control. These turned into something worse than a nightmare in 1974, when a pileup at London’s White City Stadium resulted in many fans being crushed and trampled over: One 14-year-old girl tragically died from her injuries. Cassidy quit touring soon afterward. Thereafter he seems to have suffered intermittently with depression, struggling to escape being defined as a teenage heartthrob for the rest of his adult life.

At the height of his fame, Cassidy’s fan club was judged to be bigger than that of the Beatles or Elvis Presley and he was said to receive some 25,000 letters per week. Fan ratings of present-day singers and boybands dwarf these numbers, judged from Facebook and Twitter. But for many women now in their 60s and 70s, the memory of David Cassidy still evokes nostalgia, a time of longing for romance, the poignancy of flowers pressed in blotting paper, the dream of First Love.

Carol Dyhouse is Professor of History (Emeritus) at the University of Sussex, U.K. Her most recent book, Heartthrobs: A History of Women and Desire, was published by Oxford University Press in 2017.

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli | Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson

Add a Comment