The Civil War Art of Using Words to Assuage Fear and Convey Love

Soldiers and Their Families, Sometimes Barely Literate, Turned to Letters to Stay Close

Envelope for stationary packet, "Torch of Love," George W. Fisher Bookseller and Stationer, Rochester, New York. Image courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Sarepta Revis was a 17-year-old newlywed when her husband left their North Carolina home to fight in the Confederate States Army. Neither had much schooling, and writing did not come easily to them. Still, they exchanged letters with some regularity, telling each other how they were doing, expressing their love and longing. Once, after Daniel had been away for more than six months, Sarepta told him in a letter that she was “as fat as a pig.” This may not seem like the way most young women would want to describe themselves, but Daniel was very happy to hear it.

Civil War soldiers and their families had abundant causes for worry. The men were exposed to rampant disease as well as the perils of the battlefield. Women, running households without help, often faced overwork and hunger. Letters bore the burdens not just of keeping in touch and expressing affection but also of assuaging fear about loved ones’ well-being. Yet most ordinary American families, never having endured a long separation until now, had little experience writing letters to each other. Sometimes barely literate—Sarepta had to ask her older brother to put down on paper what she wanted to say to Daniel—Americans quickly had to learn the delicate art of recreating the comforts of physical presence using only the written word.

Much of the time, they did so by writing about their bodies. In hundreds of millions of letters sent between battlefield and home front, moving across the nation by horse and by rail in recent innovations called envelopes, ordinary Americans reported the details of how they looked, what they ate, how much they weighed. Their world had been one of doing and touching rather than reading and writing, but now, by their ingenuity and resolve to hold their families together, they reshaped the culture of letter writing.

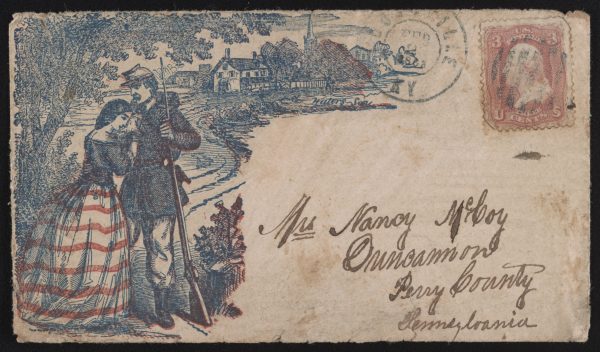

Letter to Mrs. Nancy McCoy from her son, Private Isaac McCoy of Co. A, 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, postmarked Feb. 2, 1863. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Letters were close cousins to newspapers: Only a few centuries before, in early modern England, had private letters and commercial news reporting gone separate ways (though the habit of calling journalists “correspondents” remains)—and early Americans still considered a good letter one that could “tell all the news.” Yet news was something soldiers sorely lacked. Isolated from the world beyond their regiments, awaiting orders they rarely understood, men could not satisfy their families’ yearnings for news of the war. “You can see more in the papers,” a typical soldier wrote home. Modern historians have sometimes been frustrated to find rich archives of Civil War letters that seem curiously silent on political and military affairs, but these were subjects ordinary Americans thought newspapers were covering perfectly well. What was left to them was reporting the news of their own physical selves. It may have felt a little odd at first—had Sarepta Revis gone around the house comparing herself to livestock?—but it was what families wanted, and writers found ways to oblige.

Reporting a healthy weight was one of the readiest ways to assure a distant reader you weren’t sick or malnourished. A wife as fat as a pig certainly wasn’t starving, a husband like Daniel Revis could be relieved to know, which was more important in wartime than anyone’s notions of beauty. Soldiers enjoyed the small luxury of reporting healthy weights to the folks back home in exact numbers, because they had access to scales. When regiments were encamped and relatively idle, medical staff could hold regular “sick calls,” examinations that included being weighed.

The resulting numbers made their way into hundreds, probably thousands, of letters from soldiers. Loyal Wort, a 31-year-old Ohioan in the Union Army, wrote to his wife, Susan, “i was waid the other day and waid one hundred and seventy one pounds So you See i am pretty fat.” Thomas Warrick of Alabama assured his wife, Martha, “My helth is good at this time” and, as evidence, reported, “I waide one hundred and seventy-fore pounds the last time I waide and that was the other day.” A Georgia private named Andrew White enthusiastically declared, “I way more now than I ever did in my lief I way 197 pounds.” He believed that if only he hadn’t spent an entire night out in the rain on picket duty, “I would have reached 200 pound in a Short time.” In a war that would see men’s bodies torn apart by shells and reduced almost to nothing by privation—one Union soldier lucky enough to survive the notorious Andersonville prison weighed 80 pounds at his release—numeric snapshots of the physical self acted like needles on the gauges of anxiety.

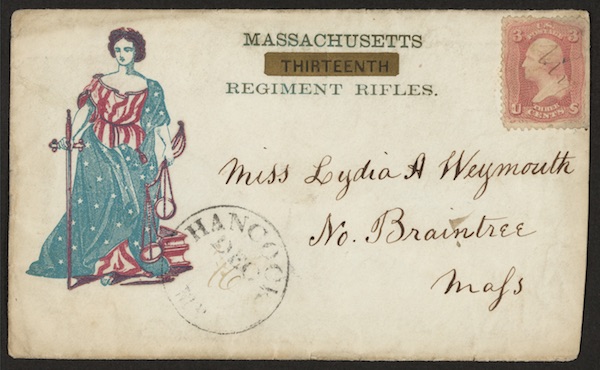

Letter to Miss Lydia H. Weymouth of North Braintree, Massachusetts, sent during the Civil War. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Pictorial snapshots had appeal, too, of course, and the relatively new technology of photography became tremendously popular among military families for similar reasons. Virtually all soldiers and soldiers’ wives who had the money and the opportunity got their portraits taken and exchanged them in the mail. An Iowa coupled joked that their photographs of each other were getting “all rubbed out” by too-frequent kissing. But photographs captured only a moment in the past. The back-and-forth of letters could document change.

For younger soldiers, especially, going to war meant proving themselves to be men and not boys, and they strove to picture themselves that way for their families. William Allen Clark wrote to his worried parents in Indiana, “If you was to see me, your doubts in regard to my health would certainly be dispelled. You wouldent see the same Slim, stoop shouldered, awkward, Gosling.” He weighed 12 pounds more than he had the previous summer. William Martin of South Carolina told his sister, “I am Now Larger than My Father My weight is Now 175 pounds.” He also wanted her to know “my whiskers is getin prity thick and they are two inches Long.” A young Georgian named James Mobley was engaged in a kind of competition with his friends: “I wayed 170 pounds and I now weigh 175 and if I keep on I will weigh 180 before long . . . Father wrote to me that John Reece said I weighted 170 and he said he weighed 177 he is only 2 pd larger than I am and I will get them on him if I dont get sick.”

When times were good—when fighting slowed, medical staff had time to make the rounds, and winter’s hardships had not set in—reports of good health prevailed, like the boasts of Wort, Warrick, and White. But the news was not always as good. If some men and women tried to spare their loved ones by withholding worrisome information, many did not. Ebenezer Coggin wrote home from a Richmond hospital that his weight had bottomed out at 105 pounds, although he insisted he was on the mend. Daniel Revis replied to Sarepta that, for his part, he was “as pore as a snake, we dont get anuf to eat.” (In 19th-century vernacular, the opposite of “fat,” “stout,” or “hearty” was “poor.”) It wasn’t what Sarepta wanted to hear, but one didn’t need a formal education to insist on honesty. “Dont tell me you feel better when you dont,” Betsy Blaisdell admonished her husband in December of 1864. She had received no letter from him in the previous day’s mail and worried it meant his recent illness had worsened. Forlorn in the cold of upstate New York—“I never dreaded winter before” Hiram left for war, she wrote—Betsy told him, nothing could “fill your place.” When Hiram’s letter of reassurance finally arrived, it featured his best effort at recreating his physical self: “I have just washed up all clean and nice,” he reported. “I guess if I was there I would have a kiss and it would not mess up your face much.”

Envelope featuring the Confederate flag, addressed to Miss Lou Taylor of Cincinnati, Ohio. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the U.S. Post Office Department had been delivering about five letters per capita annually. During the war, the average soldier sent more than five times that many. People who felt little capable of long, expressive narratives about their mental and physical well-being proved all the more resourceful in approximating bodily presence. For Americans during the Civil War, embracing loved ones on paper was a hardship they could only with difficulty overcome. Most of them, no doubt, would have rather not had to resort to it. For us, their efforts created a record of something we rarely get to see: glimmers of the emotional lives of ordinary people long gone.

Martha Poteet of western North Carolina endured labor and delivery, for at least the ninth time, during her husband’s absence in 1864. When she wrote to Francis a month later, she cheerfully described the easiest postpartum recovery she ever had experienced. “I had the best time I ever had and I hav bin the stoutest ever sens I haint lay in bed in day time in two Weeks today.” Of the baby, a girl she was waiting to name until Francis came home, Martha could report no weight—scales and doctors were rare things in the Blue Ridge.

She had a better idea. She laid the baby’s hand on scrap of paper, traced a line around it, and carefully cut it out to tuck into the envelope. Some days later, in a long-besieged trench outside Petersburg, Virginia, Francis Poteet opened that envelope and held his new daughter’s hand in his.

Christopher Hager is the author of I Remain Yours: Common Lives in Civil War Letters, just published by Harvard University Press. He is Charles A. Dana Research Professor of English at Trinity College, Connecticut.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment