The One-Size-Fits-All Sock That’s a Democratic Fashion Statement

Originally Marketed as Sportswear, the Tube Sock Became a Stylish Accessory Thanks to Farrah Fawcett and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

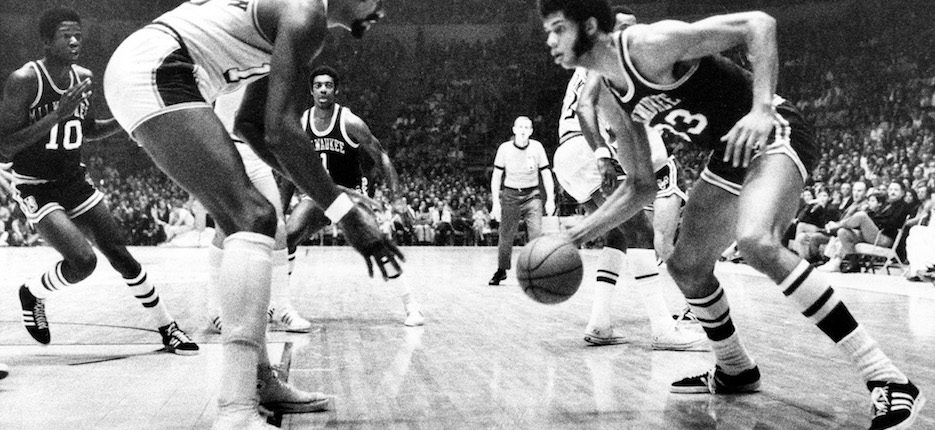

Milwaukee Bucks center Lew Alcindor (13), later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Los Angeles Lakers center Wilt Chamberlain, left, at the L.A. Forum on November 21, 1970. Photo by the Associated Press.

If you’re an American down to your toes, those toes have probably been clad in tube socks at one time or another.

These once-ubiquitous, one-size-fits-all socks are a product of Americans’ simultaneous love of sports, technological innovation, and nostalgic fashion statements.

The tube sock’s trajectory is knitted into the growth of organized sports in America, particularly basketball and soccer, both of which were popularized around the turn of the century. Basketball was a new and uniquely American diversion, played in YMCAs and school gymnasiums, while soccer was a centuries-old tradition imported by European immigrants. They had a crucial commonality, however: unlike baseball and football, they both required players to wear shorts.

With so many bare, hairy legs suddenly on display, knee-high socks—called “high-risers”—became essential accessories. As Esquire put in in 1955, shorts “look like the devil unless you wear high-rise socks with them. High-risers are usually eighteen inches, but the rule to follow is, get them up to your kneecaps. You can turn over a cuff or not—it doesn’t matter so long as they don’t end halfway down your calf.”

Photos of early basketball stars—like Chuck Taylor, who lent his name to the canvas Converse All Star high-top—show them in knee-high stockings, often with stripes placed midway (or all the way) down the leg. The increased demand for tall socks suitable for these pastimes stretched the ingenuity of the nation’s hosiery industry.

The tube sock was invented by the Nelson Knitting Company of Rockford, Illinois, just over 50 years ago, in 1967—the same year that America’s first professional soccer leagues were established. Founded in 1880 by John Nelson, the inventor of a seamless sock knitting machine, the company widely advertised its “Celebrated Rockford Seamless Hosiery.” The tube sock, though seamed, was no less monumental a technological marvel.

A true tube sock is shaped like a tube rather than, say, a human foot—a configuration so novel that the sock took its name from it. It has no heel, and, instead of a reciprocated (reinforced) toe, the end is closed with a simple seam. Nelson Knitting developed a machine expressly for that purpose, which could do the job in five or six seconds.

Eliminating the shaped heel and toe made the manufacturing process faster—about 30 percent faster than traditional shaped socks—and easier to mechanize. In addition, the tubular shape, combined with the development of new stretch yarns, allowed the sock to be made in a single size, meaning it could be produced in larger, more economical batches. These shapeless socks could be dyed, dried, inspected, and packaged much more simply and efficiently than heeled socks, all of which was reflected in their low cost.

Unfortunately, Nelson Knitting failed to patent its revolutionary design, meaning that it was immediately knocked off. This oversight may explain the style’s omnipresence in American athletic and popular culture in the late 1960s and ‘70s. Knee-high tube socks were made famous by shorts-wearing sports heroes like Björn Borg, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Pelé, and Julius “Dr. J.” Erving. Farrah Fawcett donned tube socks to go undercover as a roller derby player in an episode of Charlie’s Angels; so did Raquel Welch in the 1972 roller derby movie Kansas City Bomber.

Leaving aside its advanced physical properties, the tube sock had (and retains) a powerful emotional pull. This most democratic of accessories shapes itself to the wearer’s foot, making it both universal and intimately personal. Though tube socks have typically been produced in a single color—usually white—the ribbed elastic bands at the tops can be woven with colored stripes, indicating personal taste or group loyalty, such as team membership. Nelson Knitting supplied tube socks to a number of professional sports teams, including the knee-high socks ringed with team colors worn by the Miami Dolphins and the Washington Redskins in the 1973 Super Bowl.

Tube socks became associated not just with American sports, but with American youth, and the country’s much-mythologized landscape of suburban lawns and urban blacktop. They were ideal for growing kids because they continued to fit as children grew. And, as Good Housekeeping magazine pointed out in 1976, “any 2-year-old can put them on without hunting for a heel.” Because there were no fixed stress points, they did not develop holes as quickly as traditional socks.

The tube sock hiked up the fortunes of the American hosiery industry. A 1984 U.S. Department of Labor report attributed strong growth in the sector over the previous two decades to “advances in technology, particularly in regard to pantyhose and tube-type socks” which “reduced unit labor requirements.”

That same year, however, a new government trade deal lifted the sock tariff, opening the market to cheap imports from Honduras, Pakistan, and China. Although sock manufacturing was largely mechanized, some steps required human workers—including the seaming of tube sock toes. Lower labor costs overseas made it impossible for American mills to compete, and several shut down. Nelson Knitting filed for bankruptcy in 1985. Fort Payne, Alabama, was once the sock-making capital of the world; today, that honor belongs to Datang, China.

The Department of Labor report defined tube socks as “hosiery for casual and athletic wear.” Even today, the Fairchild Encyclopedia of Menswear states that they “are worn for athletic activity.” But the tube sock gradually transitioned from sports equipment to fashion item. It became available in a variety of lengths and colors as it was adapted for a wider range of leisure activities.

Leaving aside its advanced physical properties, the tube sock had (and retains) a powerful emotional pull. This most democratic of accessories shapes itself to the wearer’s foot, making it both universal and intimately personal.

The tube sock’s transition from sportswear to streetwear was not entirely seamless. In 1996, Vogue called the combination of black shoes and white tube socks “the unofficial male footwear of Catholic grade schools, high schools, and more senior proms than you’d care to imagine.” The tube sock was the trademark hosiery of the TV nerd Steve Urkel, and Anthony Michael Hall in any given John Hughes movie—the telltale sign of a man who was not as cool as he thought or hoped he was. It was used as a visual joke—often a dirty one—in Risky Business, That ‘70s Show, and American Pie.

Over the years, tube socks in some contexts became visual shorthand for in-your-face masculinity, often deployed ironically. In 1983, the rock band the Red Hot Chili Peppers performed a show at an L.A. strip club. For their encore, they took the stage wearing tube socks dangling from their genitals—and nothing else. Though the club’s manager was apoplectic, the “Sock Stunt” has since become one of the band’s signature concert routines—one that would be impossible, incidentally, with a shaped sock.

But sock-time does not stand still. The tube sock was not actually very comfortable to wear—the instep tended to bunch at the ankle, and the slack fit could cause blisters. Just as the humble Chuck Taylor has today been replaced by precisely engineered sneakers, tube socks have been eclipsed by similar-looking athletic socks with shaped heels. But the generic term “tube sock” continues to be used today to describe athletic socks, with or without a heel.

Modern “athletic socks” are more likely to be moisture-wicking and odor-absorbing, with graduated compression and built-in arch support. There are different socks for different sports; the idea of a runner, a shortstop, or a hiker wearing the same socks as a basketball player is anathema. Instead of one size fits all, it’s every man for himself—or every woman for herself, as most of these socks come in versions custom-designed for the female physique.

But the unassuming tube sock endures as a fashion statement for both sexes. Resurrected as street style by Harajuku girls in turn-of-the-millennium Japan, knee-high tube socks emblazoned with colorful athletic stripes turned up (in footless form) in Prada’s Fall 2004 collection. By 2016, the collision of athleisure, the “normcore” trend, and the ‘70s revival prompted Vogue to announce: “Tube Socks Are Back!”

Since then, they’ve been spotted on influencers like Rihanna, Justin Bieber, Kristen Stewart, and Tyler, the Creator; name-checked in raps by Jay-Z and Kendrick Lamar; and reinterpreted for the runway by Stella McCartney, Dries van Noten, and Valentino. It’s no stretch to imagine that the tube sock—invented, made, and worn in America— will be around for another 50 years.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is a fashion historian based in Los Angeles and the author of Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

BUY THE BOOK

Skylight Books | Powell’s Books | Amazon

Primary Editor: Lisa Margonelli | Secondary Editor: Joe Mathews

Add a Comment