1776 was a pivotal year whose legacy continues to this day to shape the politics of the nation and the lives of its citizens.

I am writing, of course, about the Lakota Nation.

In that year of transformative events, the Lakotas, according to one traditional account, discovered the Black Hills and founded the modern Lakota Nation. (The Lakotas are the westernmost of the three Sioux political divisions.)

The significance of 1776 to both Lakota and U.S. history is a trenchant reminder that North America is home to many nations and not just the three that appear so definitively on multihued National Geographic maps. Histories that focus exclusively on the rise of the modern nation-state conceal a richer, more diverse, and more complex story about the continent’s past.

In the years following the discovery of the Black Hills, the mountains became the mythic birthplace of the Lakotas, the geographic equivalent of the Declaration of Independence. Rising gradually out of the surrounding plains in the southwestern corner of South Dakota, the Black Hills culminate in a rugged granite core, a congeries of spires, knobs, and outcrops. They are “the heart of the earth, the center of our origin stories, spiritual history and sacred places,” states one tribal citizen.

The backstory to the Lakotas’ discovery is not as well-documented or widely known as the stories of the Plymouth Colony and Jamestown, but it is essential to understanding why they abandoned their traditional Minnesota homelands and established themselves in the Black Hills in the late 1700s.

Immigration historians speak of push and pull factors. In the case of American colonists, religious intolerance and poverty at home pushed many of them across the Atlantic, and the promise of cheap land pulled them in the same direction. For the Lakotas, push factors included Ojibwa villagers, who were better armed than other native peoples in Minnesota and eager to expand their hunting territories, and the decline of animal populations on the eastern edge of Sioux territory, a result of overhunting to satisfy the insatiable demand for furs in Europe.

But where to go? Two factors pulled the Lakotas across the rolling grasslands of western Minnesota and the steep gullies, high bluffs, and knife-edged ridges of the Missouri Plateau. One of them was the commercial hub controlled by the Arikaras, Mandans, and Hidatsas on the Missouri River, at the western edge of the plateau. These villagers operated a lucrative trade, funneling guns and other European manufactures to Plains Indians in exchange for horses and hides.

The conspicuous wealth of the Arikaras, Mandans, and Hidatsas made them targets, and the fortification ditches around their settlements were enormous but not up to the task of repelling assaults from highly mobile equestrian pillagers. At Larson Village, for example, skeletons recovered by archaeologists reveal that in one attack, the victims were clubbed, scalped, and decapitated. The aggressors were almost certainly the Sioux.

Lakotas raided the Missouri River settlements for as long as the villagers’ wealth lasted, but they were pulled still further west by the tens of thousands of bison that once roamed the Dakotas. One herd on the grasslands west of the Missouri reportedly stretched 150 miles. On the Great Plains, the Black Hills stand out as a green oasis. Even in dry years, its valleys are “an ocean of surging grass” that once attracted huge numbers of bison. When the Lakotas reached the mountains in the late 18th century, they found a new homeland. The Black Hills, they said, were their “meat pack.”

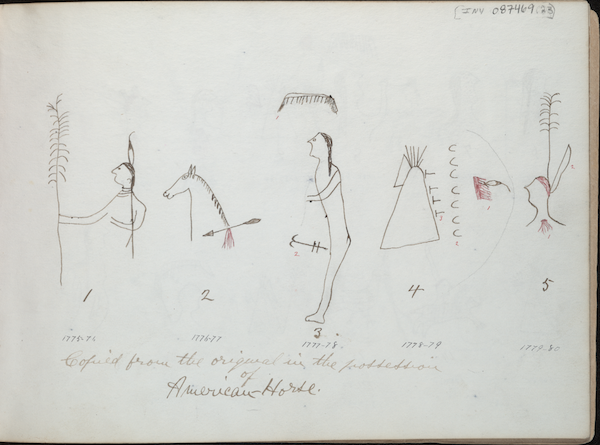

The Lakotas eventually incorporated the region’s caves and spires into their origin stories and painted its cliffs with Sioux iconography. One rock face in the southern part of the hills contains a series of Lakota symbols memorializing encounters with enemies. Five handprints, painted in red, signal victories in hand-to-hand combat, and a red spot on the same panel celebrates the death of an enemy.

On this rock and on others, the Lakotas laid claim to the Black Hills, just as revolutionaries in Philadelphia asserted their domain over the eastern seaboard with a declaration of independence. The Black Hills, the most fertile region in all of the northern Great Plains, now belonged to the Sioux.

In 1868, the United States agreed by treaty to set the Black Hills apart “for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians,” part of an effort to put an end to the constant skirmishes and battles between the Sioux and U.S. troops. When gold was discovered soon after, however, the U.S. reneged on the agreement, seizing 7.7 million acres in the Black Hills Act of 1877.

The expropriation was one of hundreds that the United States carved out of native land on its westward march across the continent, a process facilitated by the fact that colonists never fully recognized indigenous land titles. The U.S. Supreme Court enshrined the imperialist “Doctrine of Discovery” (lands belong to the sovereign of their Christian “discoverers”) in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), a case which held that native peoples enjoyed use and occupancy but not absolute title to their land.

For the Lakotas, the loss of the Black Hills was costly, both spiritually and economically. “The only place we had to run our hands in the ground and pick up money, your people have filled it up full,” the Lakota leader American Horse chastised Congress in 1890. (The Lakotas are still fighting for the return of the Black Hills.)

In 1926, three men hiked into the heart of Black Hills, hauled a winch to the summit of Mount Rushmore, fixed it into the granite, and began pulling tools up from the valley floor, 400 feet below. They were preparing to sculpt four colossal figures onto the face of the mountain. Even though Gutzon Borglum said he planned to use no explosives on any of the carving into this sacred rock, workers loaded holes with dynamite a year later and blasted away 400,000 tons.

Mount Rushmore celebrates the “continental dominion” of the United States, said Borglum, who aspired to make it “the first of our great memorials to the Anglo-Saxon in the Western Hemisphere.” It would endure for eternity, he predicted, protected in the Black Hills from “selfish, coveting civilizations” that might arise in the future. “You know how vandalism in the name of Civilization raids the tombs of our ancestors and destroys the records of History,” he observed, without a hint of irony.

As epitomized by Mount Rushmore, American history has long focused on the expansion of the United States with scant attention paid to the other peoples who lived in North America and still do so.

How we decide who is American and who is not, who belongs and who does not, is inevitably tied up with how we imagine the birth of the nation in 1776. The Lakota discovery of the Black Hills reminds us that an American history that focuses exclusively on colonists on the East Coast is partial and exclusionary. America in 1776 was more vast and diverse than we often imagine. As our population continues to diversify, we need a history that grows in kind, that encompasses the many peoples of the 18th century and speaks to all Americans in the 21st.

is the Richard B. Russell professor of American history and the associate director of the Institute of Native American Studies at the University of Georgia, in Athens. His latest book is West of the Revolution.

Buy the Book: Skylight Books, Amazon, Powell's.

Primary Editor: Jia-Rui Cook. Secondary Editor: Andrés Martinez.

Lead and interior photos courtesy of Library of Congress. Drawing courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Add a Comment