How My Parents’ Wartime Gamble on Greyhounds Paid Off

The Sentimental Journey of My WWII Childhood Mixed Dog Racing with an Idyllic Life on the Road

Author Claudette Sutherland, with one of her family's racing greyhounds. As a young child during the Second World War, Sutherland grew up on the road, traveling from track to track. Photo courtesy of Claudette Sutherland.

The greyhound racing tracks were like big shiny carnivals, but I could only see them from the outside. Kids weren’t allowed in where people were gambling. Sometimes mother took me with her and I got to watch from the lot where the dog men parked their rigs. They all knew my name and gave me bubble gum and candy. On my tip toes I could see over the fence. There were hundreds of people in the grandstand. Bright lights lit up the night sky. A marching band played while the grooms led their dogs out to the starting box. My heart pounded as the lights went out and the race began. The dogs flew by the fence in front of me, the crowds cheered and yelled, and it was over in seconds. Would I ever get to be inside where all the best things happened?

“It’s not fair,” I told Momma.

My parents made their living racing greyhounds, and it doesn’t take much to send me back to those days—the sound of a distant train whistle or the lulling hum of the highway on a long drive transports me to the backseat of our Buick on one of the endless cross-country trips my family made throughout the 1940s and 50s. Starting in the spring after a season of winter racing in Florida, we sliced diagonally across the U.S. to Oregon, where we spent a few weeks, down to Arizona where we stayed a few more, and then back to Florida for the winter, making stops all along the way. It was state lines, billboards, new schools, motels, cafes, filling stations, main streets: Just my mother, my father, and me with 25 dogs, bound by my father’s unwavering quest for a winner.

During the early years of our journeys, there was a war happening across the ocean. I had uncles, from Kansas, who were fighting in Italy. But my America was sunny and friendly, a world where my parents spent their precious ration stamps on gas, and food for the dogs. It was a time of wonder that would end, in a good way, when the war was over, and I and the country I’d watched from the back seat began growing up.

The author’s father, Paul Sutherland, and the homemade trailer he made for his dogs. Photo courtesy of Claudette Sutherland.

In the 1920s my father, Paul Sutherland, was one of many young men from landlocked Midwestern states—Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri—who were itching to get out and find adventure. They had grown up in farm country. They knew animals and crops and understood the unforgiving work required to simply stay even with nature. Every remote farm had at least a couple hounds for hunting. The dogs were also a perfect defense against pesky jackrabbits, who could level a wheat field in an afternoon.

Entertainment was hard to come by on the farms, and what existed was fashioned out of the ordinary—like a dog sprinting across a field. Greyhound racing began its evolution in the early 1900s, starting out as coursing, a sport that had travelled from England and Ireland. Two hounds were loosed on a straightaway and judged on how they maneuvered a jackrabbit over a short distance. In 1919, the first oval racing track opened in Emeryville, California, made possible by the invention of an electric lure. At first, there was no gambling, and tracks took meager profits from gate receipts, but before long the bookmakers arrived and business picked up. By 1921 there were new racetracks in Tulsa, Oklahoma; East St. Louis, Illinois; and Hialeah, Florida; six years later there were close to 32 tracks in operation across the country. In the 1930s, states began legalizing pari-mutuel gambling. With regulations in place, the racing business thrived and became a legitimate money-making proposition.

My father and mother grew up in a town called Parsons, in southeastern Kansas. My dad was working in a butcher shop and heard about dog racing from customers who came in to buy scraps for their dogs. He thought it sounded like a good way to make money and get out of town, so he bought himself a female who had a couple litters of pups, which set him up for following the tracks (all you needed was four or five dogs plus a trailer to haul them in.) Eventually, he married my mother, who joined him on the road. My birth, a few years later, didn’t slow them down a bit.

A column in The El Paso Herald offered this snapshot of my beginnings in 1940:

“Mr. and Mrs. Paul Sutherland and year-old Claudette will leave here Monday for Miami, and in the trailer behind them there will be 16 greyhounds. Let’s Go West, Small Town Mamma, War Court, Bigfoot Simpson, and Goose Girl are some of the top dogs … Claudette is probably the only baby in the country whose life is spent hopping from one place to another. Her first month anniversary was spent in Oregon, her second in San Francisco, her third in Los Angeles, fourth in Kansas, and so on, ending in Miami by the time she was six months old.”

We began our cross country trips in the pause just before dawn. My father loaded the dogs into our trailer, which he had built out of aluminum, letting me help him with the rivets. I still wore my pajamas. I could hear the dogs panting and scrabbling around as they settled into their shredded newspaper beds. The inside of our car smelled like apples and tobacco. Mother made a well for me in the back seat framed by suitcases and softened with pillows and a quilt. I had a stash of small red boxes of raisins with the pretty lady in a bonnet on the front.

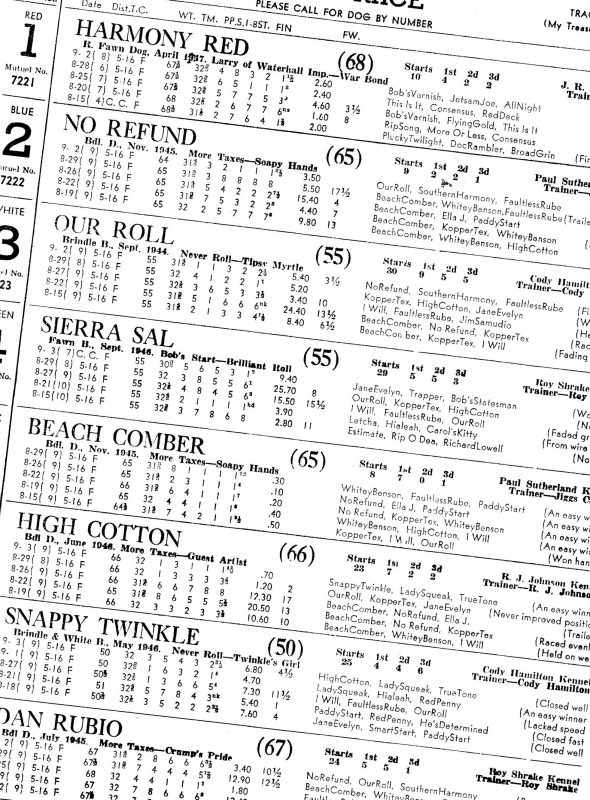

A racing program featuring Beachcomber, the Sutherland family’s champion dog. Photo courtesy of Claudette Sutherland.

We drove up through Georgia on old U.S. Route 84, through the smells of sulphur and damp red clay banks along the highway. We slipped through Alabama, clipped a piece of Tennessee, and crossed the Mississippi. We stopped at the stockyards in Little Rock to turn out the dogs in one of the mazes of connected pens. The stockyards were crowded with farmers moving livestock, and the smell of wet grain and cattle lay warm and salty across my back of my tongue. We climbed the soft Ozarks, then up into a corner of Oklahoma, and finally to Parsons, Kansas where my aunts and uncles and cousins lived. My grandpa was there too. He lifted me up on the tractor seat and told me how tall I had gotten. He showed me how to prime the pump to get the icy cold water from the bottom of the well.

From Kansas we headed north through the swaying cornfields of Nebraska, across Wyoming where you couldn’t see the end of the land and then to Idaho where we bought sacks of potatoes from the roadside caves where they were stored. We ended in Oregon, where we would race for the summer months, and where the air tasted sweet.

There were days when I wanted to not be the new girl in school all the time, the teachers always asking me to tell the class all about myself, and me always having to explain everything from the beginning. The dogs, the towns, the tracks, the kennels. Nobody’s mom and dad did what mine did. They got to live in the same house all year, and to keep the same friends and schools. I also wanted my own dog. I had a favorite. Her racing name was Vivid Girl and her nickname was Skinny. I went out to the kennels and told her when we were leaving, where we were going, and how it didn’t matter to me if she didn’t win a lot of races because I knew she was doing her best. One day, she was gone, sent back to the farm. I didn’t believe that, but nobody told me anything else.

Sometimes I got to listen to The Lone Ranger and The Shadow. In each city, the comics were different. In Miami I could read about Dick Tracy and his two-way wrist radio for catching criminals. In Oregon glamorous news reporter Brenda Starr was my hero. We tuned in to the war news on the car radio. My mother looked for letters from her brothers, who were fighting in Italy, every day. I saved the tinfoil from chewing gum wrappers and rolled the little pieces into a ball. Mother said this was for the war effort. I wondered if the soldiers would be happy when they got all the tinfoil balls. I wondered what they would use them for.

The author and her favorite dog, Skinny. Photo courtesy of Claudette Sutherland.

In 1945, the war ended and my uncles came back to Kansas. They were heroes to us. They let me wear their army caps. One became a photographer, and the other worked in a munitions plant outside the city limits. Their families soon grew. They started small businesses. America seemed to take a deep breath, ready for its bright new future.

My grandfather died, and the small farm was sold. My parents and I drove on.

In 1949 a new track opened in Denver named The Mile High Kennel Club. It was brand new—large and fancy—and best of all, minors were allowed! I got to sit in special box seats that had our name printed on a little sign, right up close to our dogs as they raced, surrounded by hundreds of strangers cheering winners on. I was where I always knew I belonged.

My father got his winner. He raised a world champion dog named Beachcomber, whose nickname was Shorty. At all the tracks we raced, Beachcomber was the biggest winner. Everyone cheered for him. He was written up in newspapers from Oregon to Arizona to Miami, and one summer, even in Mexico. Shorty became a part of our little troop, his earnings helping my parents buy property, and build a house and successful kennels. My father was famous and handsome. My mother was beautiful and happy. All the kids in school wanted to see our dogs. We had a shelf of trophies that covered a whole wall. The 1950s had arrived, America was strong and safe, and my dreams were starting to come true.

Claudette Sutherland is an actor and writer, and author of the one-woman show, Dog Man, which she performed in Los Angeles and at the Dublin Theatre Festival in 1996. She was educated at Stephens College and Yale School of Drama. She teaches creative writing in Los Angeles.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Sara Catania.

Add a Comment