It is rare to find cowboys on the silver screen who spend much time performing the humdrum labor—herding cattle—that gave their profession its name. Westerns suggest that cowboys are gun-toting men on horseback, riding tall in the saddle, unencumbered by civilization, and, in Teddy Roosevelt’s words, embodying the “hardy and self-reliant” type who possessed the “manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation.”

But real cowboys—who worked long cattle drives in lonely places like Texas—mostly led lives of numbing tedium, usually on the fringes of society. They were the formerly enslaved, poor farm boys, and downtrodden Native Americans. They enjoyed little autonomy on the trail. It was Hollywood, and men like Roosevelt, who whitewashed the cowboy, elevating him to the epitome of personal freedom, manly courage, and rugged independence.

For centuries, whether in the British Isles, the Iberian Peninsula, or the Americas, herding livestock to market put meat on the tables of city dwellers and money in the pockets of rural livestock owners. “Drove roads,” the term for routes through which livestock were driven, laced the countryside of rural England and Colonial America, connecting local communities to urban centers and generating millions of dollars in trade.

While turning cattle into capital could be lucrative for livestock owners, herding this “cash on the hoof” remained the job of low-status workers. In southern Appalachia during the 18th and 19th centuries, “cow keepers” used whips and dogs to control their herds, and if the term “cowboy” was used it was almost certainly pejorative. During the same era, in Mexico, the task of herding cattle fell to vaqueros, a multiracial, low-status group who transformed what had been a pedestrian chore into an equestrian art. Their lazo (rope with a slip knot) became a lasso, chaparajos became chaps, and sombrero became the ten-gallon hat. Because vaqueros were largely of indigenous descent, one could say that all of these early cowboys were in fact “Indians.”

In mid-19th-century Texas, millions of cattle grazed the open range—and many Texans preferred to gather wealth in cattle, which multiplied every year, to amassing wealth in land. But the rough task of gathering and herding cattle was considered an occupation beneath the dignity of respectable people. Herders roamed the mesquite thickets, coastal savannahs, and brush lands of eastern Texas capturing and branding any cattle they could find, seldom bothering to determine an animal’s ownership before taking it to market. Texas newspapers warned against “this roving class of worthless characters” who “may forget that there is a distinction between ‘mine’ and ‘thine.’” Polite families would no sooner invite a cowboy to dinner, Montana rancher Nannie Alderson wrote, than they would a rattlesnake.

Things changed after the Civil War when Texans began driving longhorn cattle hundreds of miles to the railroads in Kansas, in what became the longest, largest forced migration of animals in history. In Texas a steer might sell for only a few dollars; in Kansas, where livestock could be transported by rail directly to stockyards in Chicago, it might bring $30 or $40.

Texans who could marry their backcountry herding skills to the entrepreneurial demands of the Gilded Age stood to make fantastic profits. Some of these successful Texas cowboys became leading symbols in the new Western myth. Charles Goodnight found instant fame when he teamed with renowned cattleman Oliver Loving, hired a crew of impoverished ex-Confederates and a formerly enslaved person named Bose Ikard, and pushed a herd through the west Texas desert into New Mexico and then north to Denver. Selling the animals at $60 per head, he returned to Texas with $12,000 in gold, enough to build a fortune, as a legendary cattle driver and rancher. He is sometimes called “the father of the Texas Panhandle.”

Still, what actually occurred on these long drives wasn’t glamorous. Cattle herding was no place for free thinkers or independent minds. Like any other industrial-age enterprise, the cattle drive was built around guiding principles of centralized control, monotonous routines, and a disciplined labor force. It was “systematically ordered,” as Goodnight said.

Driving two or three thousand cattle over 1,000 miles required a dozen or so cowboys, each with four or more horses, working for three to six months. The trail boss, who might be the ranch owner but was more likely an experienced ranch hand, rode ahead of the herd to control the pace and direction of travel and tolerated neither unruly cattle nor rebellious laborers. Cowboys took orders and worked for wages typically lower than skilled factory pay.

Each herder had a regular position in the herd, from lead to flank to swing to drag, with status and sometimes pay according to position. According to Montana cowboy Edward Charles “Teddy Blue” Abbott, this “cowboy rank” meant that “every man knew his place and what to do.” Drag riders had it the worst. Responsible for bringing along the poor, weak, or wounded animals, drag riders would end the day “with dust half an inch deep on their hats and thick as fur on their eyebrows,” Abbott said. Even worse was the dust in their lungs, which had them coughing up brown phlegm for months after the drive.

In mid-19th-century Texas, millions of cattle grazed the open range—and many Texans preferred to gather wealth in cattle, which multiplied every year, to amassing wealth in land. But the rough task of gathering and herding cattle was considered an occupation beneath the dignity of respectable people.

Most riders on the drives were out-of-work farmers’ sons, some as young as 12 years old, who saw the opportunity to trail cattle as both a rare paying job and a rite of passage. African-American cowboys earned less and were often required to take on more dangerous tasks. Vaqueros also worked the herds. Bosses recognized their superior roping and riding skills but paid them less than Anglo riders. A few women went up the trail, mostly as wives in wagons accompanying the herds. In 1888 a young girl named Willie Matthews disguised herself as a boy and worked, rode, and roped along with the rest of the crew.

These diverse workers, a proletariat on horseback, shared in the grinding monotony of the trail—and often said as much. According to 19th-century Kansas journalist Henry King, who interviewed many trail riders as they arrived in Dodge City, repetitious chores caused cowboys to feel “adrift on these great, vague, and melancholy prairies.” One cowboy complained, “The trip that was once so exciting and thick with adventure has come to be an unspeakably cheerless and tiresome thing.”

Even the food was monotonous: Beans and biscuits constituted the standard fare. While the cowboys were surrounded by beeves—as they called cattle destined to become meat—eating into the boss’s profit margin was not an option. According to 19th-century Kansas cattle buyer Joe McCoy, who established the first cattle trading center in Abilene, Kansas, and later wrote a detailed description of the cattle trade, the unhealthy diet, along with a lack of tents, blankets, or even clean water, sapped the youthful vigor of cowboys and caused them to become “sallow and unhealthy” and “half-civilized only.” For some, “gloom” and “depression” descended on the crew until “conversation dwindled into monosyllables.” The legendary strong, silent type—so well-known from so many classic movies—may have emerged from the unspeakable boredom of trail life.

Wearisome dullness was occasionally interrupted by the sheer terror of the stampede. Longhorns had a strong flight instinct and a thunderstorm, an unexpected noise, or even the shake of a blanket could send them scattering. This sudden, unexpected, and seemingly aimless mass flight would shake the ground like an earthquake and crush any luckless herder caught in its path. At best, a stampede meant several days and nights of chasing after stray bunches of cattle. Combined with regular shifts of riding night duty, this meant that cowboys stayed in the saddle for three days or more. In such times coffee was not enough, Teddy Blue Abbott said. The only way to stay awake was to rub tobacco juice in one’s eyes.

For some cowboys, the hardest moments along the trail were the almost daily killings of newborn calves. Some herds were entirely steers (neutered males) headed for market, but others consisted of cattle of mixed sex, including pregnant cows. Newborn calves could not be tolerated because they slowed the herd. According to his biographer Charles Goodnight said, “We killed hundreds of newborn calves on the bed grounds. I always hated to kill the innocent things, but since they were never counted in the sale of cattle the loss of them was nothing financially.” The duty to “murder the innocents” each morning typically was assigned to a lower-status worker, either one of the younger members of the crew or an African-American, who shot the calves dead. One such worker, Branch Isbell, became so disgusted with “being the executioner” that he swore off using or owning guns for the rest of his life.

Despite the prevalence of lethal firearms and “Indian” fights in Western movies, there wasn’t much evidence of either in the actual cattle drives. Many trail bosses required their workers to keep their pistols in the chuck wagon, for fear that gunshots would cause a stampede. A cumbersome six-shooter was heavy to wear and had no real use in most trail situations. And besides, carrying pistols in public was illegal in Texas settlements and in the Kansas cattle towns at the end of the trail.

The famous Chisholm Trail passed through Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma, and some Native nations along the path, notably the Creeks, Cherokees, and Chickasaws, charged a fee for cattle crossing their land. Some Texas drovers claimed they fought back, and told manly stories of staring down the menace while brandishing their Winchesters. More commonly, however, they hired Native American cowboys to help herds across rivers or to find strays after a stampede. While the “Indian” threat loomed large in the Texas imagination, trail drives were marked more by cooperation than conflict.

There was one way in which actual cowboys helped forge the cowboy myth—in the downtime herders enjoyed as soon as they arrived in Kansas cattle towns. After bathing and shaving, but before heading to the saloon, they traded in their homemade trail clothes—straw or felt hats, flannel shirts, durable pants—for what some called the “working costume” of the cowboy: ten-gallon Stetsons, fancy shirts, leather chaps, star-topped boots, and sometimes a fancy pistol. Thus styled, they went to the photographer, posing for photos that wound up in newspapers, galleries, and archives across the country.

This visual legacy is about as accurate as using high school prom pictures to portray the typical attire of today’s teenager. But it made an indelible impression. Through popular culture, fictional cowboys became the antidote to worrisome urbanization and soul-killing industrialization that Gilded Age Americans needed.

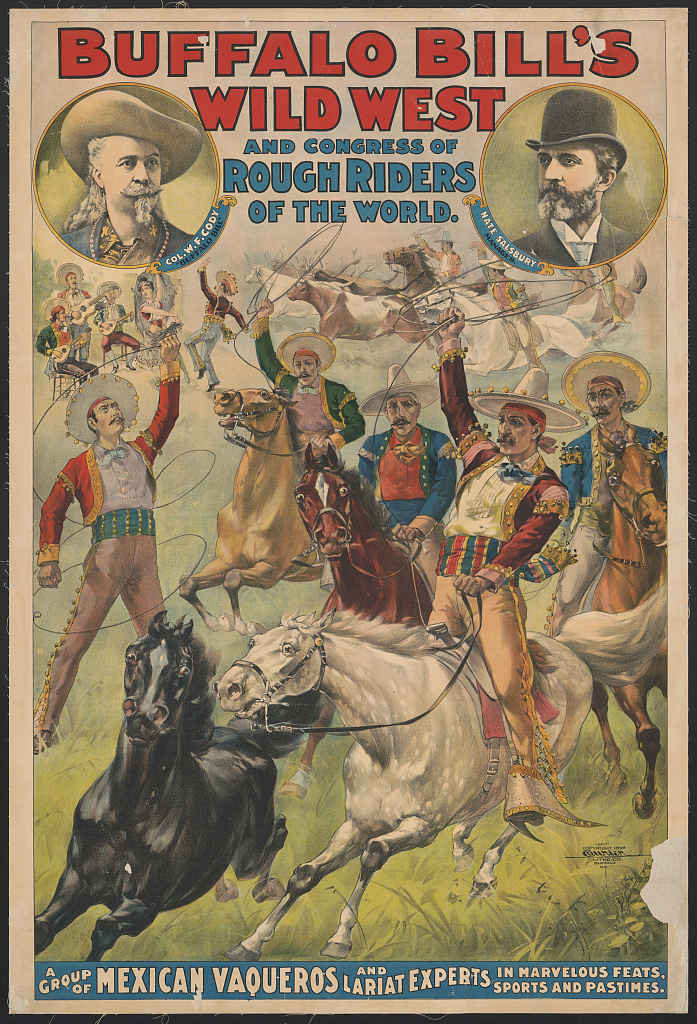

Buffalo Bill Cody borrowed the image of the heroic cowboy for his Wild West shows, choosing a trail rider from Texas, Buck Taylor, to perform riding and roping tricks for his Eastern audiences. Tall, lean, and handsome, Taylor quickly became known as “King of the Cowboys,” a moniker he kept when he became the model for dime novels in the 1880s, written in as little as 24 hours and sold to millions of Eastern readers seeking escape from the regimented world of cities and factories. The books, like later Hollywood Westerns, thrived on the notion of the cowboy as individualist and gun-toting adventure hero. They had no use for the monotony and hardship of a cattle drive—the real life of the cowboys.

Tim Lehman is a historian at Rocky Mountain College in Billings, Montana, and the author of Up the Trail: How Texas Cowboys Herded Longhorns and Became an American Icon.

Buy the Book

Skylight Books | Powell's Books | Amazon

PRIMARY EDITOR: Eryn Brown | SECONDARY EDITOR: Joe Mathews

Add a Comment