The Black-Owned Alabama Plantation That Taught Me the Value of Home

After Emancipation, Ex-Slaves Took Over the Cotton Fields. Today Their Descendants Still Cherish the Land.

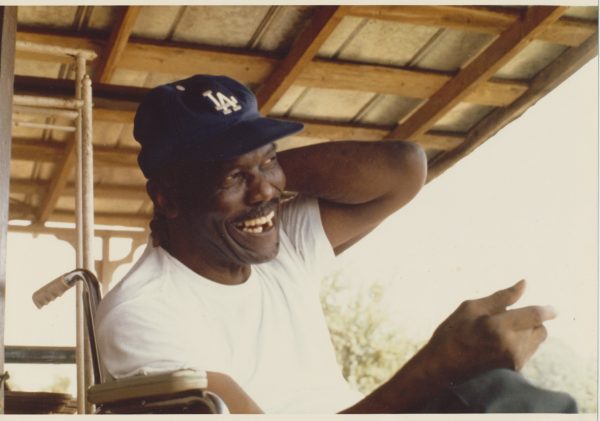

James Lyles, 69, one of the descendants of former slaves who bought the Alabama cotton plantation where they'd formerly toiled. Lyles and other descendants held the property in common and undivided, to be shared by all the heirs. Photo courtesy of Sydney Nathans.

By the time I was eight years old, in 1948, my parents, my sister, and I had lived in five different states and had moved more often than that. My grandparents had emigrated from Europe to America early in the 20th century. Somehow I took it for granted that staying in one place for a long time was, if not un-American, at least unusual.

When I became a historian in the 1960s, I gravitated to a man on the move and through him achieved mobility myself. I wrote a book about Daniel Webster, the greatest orator of his day, who progressed from New Hampshire farm boy in the 1790s, to Massachusetts Senator in the 1830s, to U.S. Secretary of State in the 1840s. Riding his coattails, I moved from merchant’s son in Texas to college professor in North Carolina.

So nothing in my experience prepared me for what I found when I ventured to Alabama in 1978 on a very different project—namely, to see if I could locate descendants of enslaved African Americans who had been sent to work a plantation in western Alabama in 1844. I wanted to learn if they had an oral tradition that might shed light on the Great Migration of the 19th century. Termed by historians as the Second Middle Passage, that disruptive event, which took place between 1815 and 1860, forcibly moved a million enslaved persons from the eastern part of the South, where none of the mainstay crops—tobacco, wheat, corn—paid as handsomely as cotton, which grew bountifully to the west. By the thousands, black workers were relocated to Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, where they would toil on the rich, cotton-growing soils of those newly settled states.

I found many descendants of these dislocated workers, who told me stories from the vivid oral tradition about the forced migration. But, to my amazement, I also came upon the incredible story of one family whose first freed generation bought the 1,600-acre plantation of their former owner, a distressed property known as the Cameron plantation in Hale County, Alabama, where cotton had once grown. Their descendants shared with me the history of subsequent generations, who remained on the land throughout the 20th century and into the second decade of our own time.

Many of us are familiar with the dramatic story of the Great Migration of the 20th century, the saga of millions of rural black Southerners who left the poverty and Jim Crow shackles of the region for the cities of the North, Midwest, and West, a tale most recently chronicled in Isabel Wilkerson’s magnificent oral history, The Warmth of Other Suns. But as historian Eric Foner has noted, many more African Americans stayed in the South than left—albeit most on land different from the plantations where they’d been held in bondage.

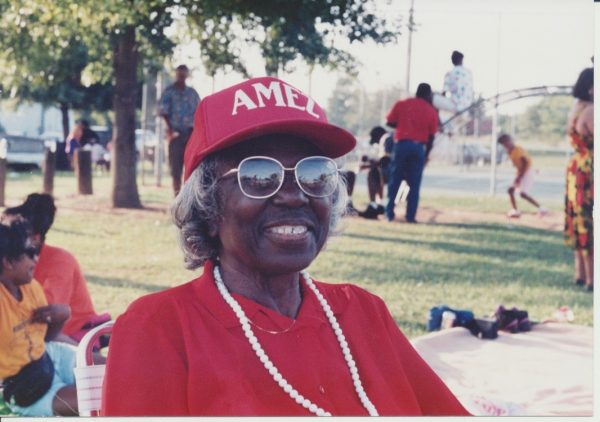

The descendants of Alice Hargress. Photo courtesy of Sydney Nathans.

What happened at the Cameron plantation was historically unusual. As a research subject, it was unusual as well. Generations anchored on a single stretch of land, documented in a white planter’s archives and black families’ oral histories, allowed me to trace a narrative of black life in a single community from 1814, three decades before the migration to the west, forward to 2014.

It took me some time to realize that this history of continuity was emblematic of a much bigger story—that of the millions of African Americans who remained in the rural South, for a century and a half after Emancipation. It is the story of when and why black-owned land mattered, and matters still.

No one knew the history of the black people who bought the Cameron plantation better than one man. Louie Rainey, I came to find out, was the oral historian of the community. Born in 1906, he grew up in the household of his grandmother, who shared stories of slavery and freedom with her inquisitive grandson. Gifted with a prodigious memory, Louie Rainey became a collector of narratives for the entire settlement. For decades, his porch was the place where everyone came to visit, the old to share stories of the past, the young to hear him retell the tales. On that porch, starting in 1978 and until his death in 1986, he shared those vivid accounts with me.

“You can go where you want to go, can do what you want to do!”

That’s what Louie Rainey’s grandmother told him that she heard at the “speakin’” at nearby Greensboro, Alabama in June 1865, where the head of the Freedmen’s Bureau told her and thousands assembled in town, “You’re free, you’re free!” Many newly emancipated men and women of that first generation collected their spare belongings and moved, eager to leave behind planters, overseers, and places where they’d been held captive. But on the Cameron plantation, Louie Rainey and others told me, emancipated people found ways—already in place—to achieve their foothold in freedom.

Louie Rainey. Photo courtesy of Sydney Nathans.

Paul Hargis, his two brothers and their wives, who had been enslaved on the property, bided their time after Emancipation, staying put “against all comers” despite crop failures and better prospects elsewhere that led others to depart. The Hargis brothers knew from the plantation overseer that the planter wanted to sell out; if they remained, they might be among the buyers.

The chance they had been waiting for came in the 1870s, when they bought 100 acres from their former master, a man named Paul Cameron, who by 1873 was indebted and ready to sell. The Hargis family made a deal with the hard-pressed planter on the only terms they could afford and he could get—no money down, and five years to pay their debt in cotton. Their gain was not only self-supervision. Acquiring the land also allowed them to keep their family intact. For the rest of the 19th century and into the 20th, family members made a living off their land by staying and farming together.

Paul Cameron sold the rest of his plantation in parcels to eight other families who had worked his land. For Eli Williams, land ownership provided liberty undreamed of in bondage. He hired others to work his crop, and spent his days riding round the settlement high on a horse, sporting a wide-brimmed hat, wearing a blue chamois shirt with a high “city-lawyer collar.” Slavery had been on his master’s terms. Freedom would be on his own.

For severely bow-legged freedman Tom Ruffin, farming and riding were out. Instead, he learned how to manage oxen, and parlayed his skill into hauling timber, hiring hands, and earning enough to become the largest black landowner in the county. Asked often by baffled whites how he’d acquired 2,000 acres, he cagily replied, “I worked while you slept—and if you’d slept another wink, I’d a got it all!”

For the second generation, the children of those who bought the plantation, the primary goal shifted to holding on to the land. Overuse and land division made their farms less productive than places worked by sharecroppers and renters on adjacent white-owned properties, which had richer soil. But from their vantage point, land ownership still gave them sanctuary from pressures to which their landless neighbors had to bow: deference to white owners, demands always to yassir and yes-ma’am white bosses, silent acceptance of year-end settlements where they always seemed to come out in debt. Worst of all, second-generation landowner Alice Hargress told me, many renters came to think that they simply couldn’t get along without “cap’n bossman.” Then, she said, “they were truly lost.”

Alice Hargress. Photo courtesy of Sydney Nathans.

Land meant even more during the Great Depression, which descendant James Lyles called “that Thirties wreck.” The New Deal agricultural policy of controlling “overproduction” led to massive evictions of sharecroppers and renters, turning dispossessed tenants into tramps. However depleted their soils, landowners didn’t “have to git!” After World War II, the third generation of landowners watched its sons and daughters leave farming for “the warmth of other suns,” as Richard Wright poetically termed hopes pinned on the North and West. Nonetheless, those who remained held on to the land for new reasons. Some hoped, vainly it turned out, that changing to different crops and joining in cooperative credit and marketing ventures could allow them to make a living even after cotton was replaced by cattle and catfish.

Others like Alice Hargress and James Lyles chose to keep even unremunerative land intact—for those who left to come back to, if they ever wished to return. They called it “heir land,” property held in common and undivided for “all the heirs.” If those who left fell short in their new lines of work, they wouldn’t have to become late-20th-century tramps.

Realistically, though, would those who fled ever wish to return to a South where, outside the bounds of their settlement, blacks “had to bend?” In 1965, the 51-year-old Alice Hargress and 69-year-old James Lyles faced up to that question, and marched to make Greensboro—and Alabama—a place to which their children want might to come home. They joined Civil Rights demonstrations that summer, endured tear gas, and went to jail. They gained voter rights for themselves and their children and grandchildren.

Fulfillment came, starting in the 1970s. Four of Alice Hargress’ eight children did move back to Alabama after working in California. They headed home to retire, look after their mother, and reconnect with relatives and friends who never left. Thousands more also decided to come back to the rural and small-town South at that time, an unexpected return-migration beautifully depicted by anthropologist Carol Stack in her 1996 book, Call to Home. Today, passing by the black-owned enclave of the former Cameron plantation, you can see a few older dwellings and a number of newer trailers, homes of those who have returned to “heir land.” Their return—and that of others to the rural South—has vindicated the striving of generations before them and replenished the community that landowning anchored and made possible.

By the early 1980s, I realized that I too had become an heir—not to property but to the family heritage which Alice Hargress and Louie Rainey and so many others generously shared with me. Alice Hargress died in August 2014, 18 days shy of her 100th birthday. For more than 30 years, she made her home my home, and her history my history. Her family’s story and example taught me not only why black land mattered. It taught me the transcendent importance of a home place: for them, for African Americans, and—no longer a tumbleweed—for myself.

Sydney Nathans is Emeritus Professor of History, Duke University. He is the author of the award-winning To Free a Family: The Journey of Mary Walker (2012) and of A Mind to Stay: White Plantation, Black Homeland (2017), which tells the story of the Cameron plantation.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown | Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment