The Republicans are convening in Cleveland, and the Cleveland Cavaliers have won the NBA championship after a half-century long drought for Cleveland sports teams, putting intense focus on the city’s past and present. And so I, as a historian, keep getting asked to describe the “essence” of the city in which I live and which I have studied for a number of years.

Most inquiries ask what makes Cleveland special. Too often, the responses that are given to the media are civic booster-speak. Once the fifth-largest city in the nation, John D. Rockefeller did create Standard Oil while in Cleveland. But one must be be wary about firsts, subjective rankings of contributions, or people that have “changed the way we live.”

Calling the city “special” can be problematic. Cleveland fits the pattern of many other midwestern industrial cities, particularly those situated on the Great Lakes. As a historian, I long for more studies that contextualize not only our industry but also social life, class, and benevolence in Cleveland with other cities, particularly during the years just before and including the turn of the 20th century known as the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

The Gilded Age intrigues me because it is the era in which landscape, philanthropy, and migration coalesced to make Cleveland an important player in the nation’s economy and political life as well as in culture and education. Landscape, diversity and philanthropy gave Cleveland a significant history and primed the city for future growth—including some of the gains of today’s post-industrial era.

Cleveland’s location, on a lake (Erie) at the mouth of a river (the Cuyahoga), is not special. Classically, many cities were perched on waterways for transit and trade. That’s why Moses Cleaveland, the leader of the first survey party in 1796 and the city’s namesake, decided to establish the town at the site. He expected the community to develop as the mercantile center for a surrounding agricultural hinterland. But, it would become far more than an agricultural entrepot. The discovery of iron ore, coal, limestone, petroleum, and other natural resources in the regions around the lakes in Ohio and Pennsylvania some 50 years later, would transform a community of merchants into a community of industrialists, inventors, and workers. Efficient transport networks, canals, railroads, and lake shipping provided links to markets and resources and by the late antebellum era, created the foundation for a period of immense growth.

Today, landscape and place still play significant roles for the city and the surrounding region, but the impact extends beyond commerce. Like other industrial cities that had a “lock” on business and industry because of their water and rail networks, Cleveland’s jobs and factories begin to exit the area via the new postwar highway networks, and later through channels of global industrialization. But, the lake remains, as does a now relatively clean Cuyahoga River. Both now are seen as lifestyle amenities and while both still carry commerce, they have also anchored waterfront entertainment venues and other recreational attractions. The waterfronts are also an important part of the sales pitch for businesses seeking new workers in the competitive high-tech and medical labor markets. But the lake’s most significant quality is its looming future importance beyond lifestyle given the realities of climate change. There is no shortage of water in Northeast Ohio.

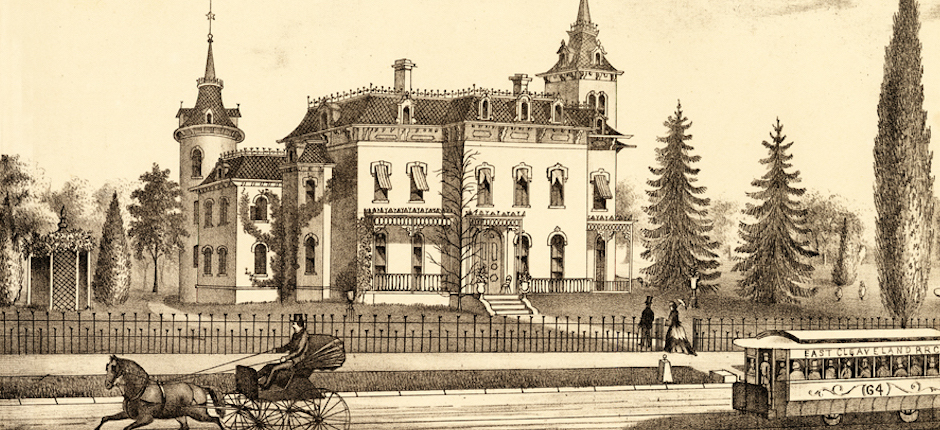

While acknowledging the importance of the lake and river, many citizens still lament the loss of industry and the extravagant lifestyle they link to the industrial barons who lived in the region, with a palpable nostalgia for old Euclid Avenue, once known as Millionaires Row. The area once hosted dozens of spectacular homes that were ostentatious showcases of Gilded Age wealth. Several remain, but the splendor is gone. Yet, the legacy of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era wealth of the city is embedded in many of Cleveland’s cultural, medical, educational, and social service institutions.

One can argue that the barons of the Gilded Age should have paid their workers more and spent less on dividends, charity, and culture. That’s an interesting question for me, given that my immigrant grandfathers worked in the steel mills, and that today, I work for two institutions, Case Western Reserve University and the Western Reserve Historical Society, whose growth was supported in large part with Gilded Age money. The futures of those institutions depend on a continuity of a local philanthropic tradition.

This legacy money—which also created Severance Hall, the home of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and University Hospitals—is now being joined by funds provided by a more diverse set of donors. A drive or bus ride down Euclid Avenue today shows not mansions, but an always-evolving medical, educational and cultural complex. The names (such as Ahuja, Seidman, Mandel and Wolstein) on the newer buildings on the avenue and in University Circle indicate the manner in which the New England tradition of community stewardship has been augmented by communities that arrived in the years since the 1830s. Call it what you will: stewardship, tzedakah, or charity, these traditions of altruism have been central to the city’s history and have created institutions that seem to be anchoring its future.

The diversity of names on the buildings on Euclid Avenue and in University Circle is the result of a process that the founders never expected. They envisioned Cleveland as an outpost of New England. That’s why they laid out a town square at its center. But the growth of commerce and industry attracted a global population. The immigrant and migrant flow provided not only cheap, replaceable labor in the factories, but also skill sets and ideas critical to innovation. In 1920, two-thirds of the population of nearly 800,000 was of foreign birth or foreign parentage. Another 35,000 residents were African-Americans, the majority having come in the years since 1900. As was the case in Chicago, Buffalo, Detroit, and other cities, they created a web of neighborhoods anchored around their workplaces and a network of culturally attuned stores and businesses.

Today, some of the “Ellis Island” neighborhoods endure, their identities marked not so much by the ancestry of their current residents, but by structures, stores, and restaurants. They are home to the city’s evolving “foodie” culture, to many young professionals, and to the beginnings of gentrification. That diversity also colors memory—in positive and negative ways—among Clevelanders with deep roots in the city. There is still, despite recent demographic changes, a local passion for remembering roots and ancestry. The question often asked of a newcomer in Cleveland is not “What do you do for a living?” but “What are you?” in terms of one’s ethnic identity.

All of this is happening in a city and region in which the percentage of foreign-born is now well below the national average, whereas between 1860 and 1950, the city was well above average. Yet, the number of national/ethnic identities is now larger than ever before. Some estimates put it at over 110. So, on one scale the city is not as “ethnic” as it was in terms of numbers, but on another, the region is more globally representative than ever.

Here too, some see the future in the past, arguing that immigrants can bring new skills and viewpoints to the city and to the workplace, and that a more globalized Cleveland would better reflect the broader world in which it exists. Some local groups focus on attracting skilled immigrants, while others see the city as a home for refugees who could acquire skills and settle in the city. Indeed, there are many open spaces in Cleveland, a city that once housed over 900,000 people and now has fewer than 400,000. Perhaps those spaces could provide refuge. However, the matter of diversity is encumbered by political rhetoric. There is also the question of who would be displaced in the job market if there were an influx of new job-seekers competing for the non-technical, less skilled jobs in the region.

Yet the city has “been there” before in this regard. In some instances—industrial strikes and urban unrest—the consequences have been brutal. Yet, what was to be a bit of old New England did transform itself and survive. Cleveland’s future will need to echo a past in which it transcended the location that gives it an identity and came to embrace ideas, skills, and concepts of altruism from around the globe. Does that make it different or special? Perhaps. But even if not, it is a city with a history that begs for further exploration.

In “Beyond the Circus,” writers take us off the 2016 campaign trail and give us glimpses of this election season’s politically important places.

, Ph.D, is Krieger-Mueller Associate Professor of Applied History at Case Western Reserve University and historian/ senior vice president for Research and Publications at the Western Reserve Historical Society. He also serves as editor for the online Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

This essay is part of Cleveland: Why the Host of the Republican Convention Sees Its Future in the Rear View Mirror, a special inquiry from Zócalo Public Square.

Primary Editor: Hattie Hayes. Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli.

*Lead image courtesy of Atlas of Cuyahoga County, Ohio/Wikimedia Commons. Interior image courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Add a Comment