When Barnum and Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth” rolled into American towns in the 1880s, daily life abruptly stopped. Months before the show arrived, an advance team saturated the surrounding region with brilliantly colored lithographs of the extraordinary: elephants, bearded ladies, clowns, tigers, acrobats, and trick riders.

On “Circus Day” (as it was known), huge crowds gathered to observe the predawn arrival of “herds and droves” of camels, zebras, and other exotic animals—the spoils of European colonialism. Families witnessed the raising of a tented city across nine acres, and a morning parade that made its way down Main Street, advertising the circus as a wondrous array of captivating performers and beasts from around the world.

For isolated American audiences, the sprawling circus collapsed the entire globe into a pungent, thrilling, educational sensorium of sound, smell, and color, right outside their doorsteps. What townspeople couldn’t have recognized, however, was that their beloved Big Top was also fast becoming a projection of American culture and power. The American three-ring circus is uniquely tied to our nation’s history: It came of age at precisely the same historical moment as the U.S. itself.

Three-ring circuses like Barnum and Bailey’s were a product of the same Gilded Age historical forces that transformed a fledgling new republic into a modern industrial society and rising world power. The extraordinary success of the giant three-ring circus gave rise to other forms of exportable American giantism, such as amusement parks, department stores, and shopping malls.

Arkie Scott astride his horse, Harold, leads a parade of elephants down Eighth Avenue at Madison Square Garden in New York, March 28, 1954.The Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus came to town for a 40-day engagement. Photo by Jacob Harris/Associated Press.

The first circuses in America were European—and small. Although circus arts are ancient and transnational in origin, the modern circus was born in England during the 1770s when Philip Astley, a cavalryman and veteran of the Seven Years War (1756-1763), brought circus elements—acrobatics, riding, and clowning—together in a ring at his riding school near Westminster Bridge in London.

One of Astley’s students trained a young Scotsman named John Bill Ricketts, who brought the circus to America. In April of 1793, some 800 spectators crowded inside a walled, open-air, wooden ring in Philadelphia to watch the nation’s first circus performance. Ricketts, a trick rider, and his multicultural troupe of a clown, an acrobat, a rope-walker, and a boy equestrian, dazzled President George Washington and other audience members with athletic feats and verbal jousting.

Individual performers had toured North America for decades, but this event marked the first coordinated performance in a ring encircled by an audience. Circuses in Europe appeared in established urban theater buildings, but Ricketts had been forced to build his own wooden arenas, because American cities along the Eastern Seaboard had no entertainment infrastructure. Roads were so rough that Ricketts’ troupe often traveled by boat. They performed for weeks at a single city to recoup the costs of construction. Fire was a constant threat, due to careless smokers and wooden foot stoves. Soon facing fierce competition from other European circuses hoping to supplant his success in America, Ricketts sailed for the Caribbean in 1800. While returning to England at the end of the season, he was lost at sea.

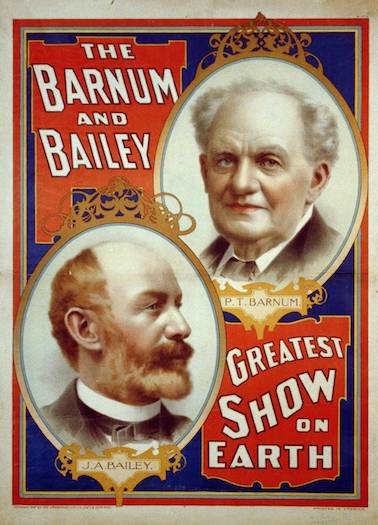

An 1897 poster advertising Barnum and Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth.” Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

After the War of 1812, American-born impresarios began to dominate the business. In 1825, Joshua Purdy Brown, a showman born in Somers, New York, put a distinctly American stamp on the circus. In the midst of the evangelical Second Great Awakening (1790-1840), an era of religious revivalism and social reform, city leaders in Wilmington, Delaware, had banned public amusements from the city. Brown stumbled upon the prohibition during his tour and had to think fast to outwit local authorities, so he erected a canvas “pavilion circus” just outside the city limits.

Brown’s adoption of the canvas tent revolutionized the American circus, cementing its identity as an itinerant form of entertainment. Capital expenses for tenting equipment and labor forced constant movement, which gave rise to the uniquely American one-day stand. On the frontier edges of society, entertainment-starved residents hungrily flocked to the tented circus, which plodded by horse, wagon, and boat, pushing westward and southward as the nation’s borders expanded.

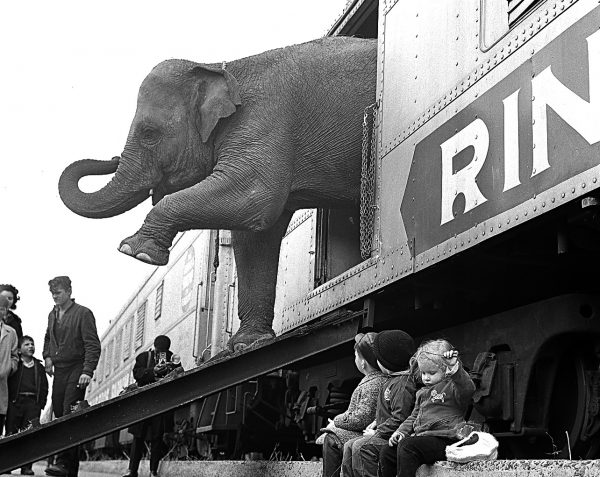

The railroad was the single most important catalyst for making the circus truly American. Just weeks after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May 1869, Wisconsin showman Dan Castello took his circus—including two elephants and two camels—from Omaha to California on the new railroad. Traveling seamlessly on newly standardized track and gauge, his season was immensely profitable.

P.T. Barnum, already a veteran amusement proprietor, recognized opportunity when he saw it. He had set a bar for giantism when he entered the circus business in 1871, staging a 100-wagon “Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Circus.” The very next year, Barnum’s sprawling circus took to the rails. His partner William Cameron Coup designed a new flatcar and wagon system which allowed laborers to roll fully loaded wagons on and off the train.

Barnum and Coup were outrageously successful, and their innovations pushed the American circus firmly into the combative scrum of Gilded Age capitalism. Before long, size and novelty determined a show’s salability. Rival showmen quickly copied Barnum’s methods. Competition was fierce. Advance teams posting lithographs for competing shows occasionally erupted in brawls when their paths crossed.

A Ringling Brothers Circus elephant walks out of a train car as young children watch in the Bronx railroad yard in New York City, April 1, 1963. Photo by Associated Press.

In 1879, James A. Bailey, whose circus was fresh off a two-year tour of Australia, New Zealand, and South America, scooped Barnum when one of his elephants became the first to give birth in captivity at his show’s winter quarters in Philadelphia. Barnum was begrudgingly impressed—and the rivals merged their operations at the end of 1880. Like other big businesses during the Gilded Age, the largest railroad shows were always prowling to purchase other circuses.

Railroad showmen embraced popular Horatio Alger “rags-to-riches” mythologies of American upward mobility. They used their own spectacular ascent to advertise the moral character of their shows. Bailey had been orphaned at eight, and had run away with a circus in 1860 at the age of 13, to escape his abusive older sister. The five Ringling brothers, whose circus skyrocketed from a puny winter concert hall show in the early 1880s to the world’s largest railroad circus in 1907, were born poor to an itinerant harness maker and spent their childhood eking out a living throughout the Upper Midwest.

Collectively, these self-made American impresarios built an American cultural institution that became the nation’s most popular family amusement. Barnum and Bailey’s big top grew to accommodate three rings, two stages, an outer hippodrome track for chariot races, and an audience of 10,000. Afternoon and evening performances showcased new technologies such as electricity, safety bicycles, automobiles, and film; they included reenactments of current events, such as the building of the Panama Canal.

Kenneth Lucas, clown photographer, takes a picture of Felix Adler, “The King of Clowns,” at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in New York, May 2, 1944. Adler feeds a piglet with a bottle to the delight of the children in the audience. Photo by Charles Kenneth Lucas/Associatrd Press.

By the end of the century, circuses had entertained and educated millions of consumers about the wider world, and employed over a thousand people. Their moment had come. In late 1897, Bailey took his giant Americanized circus to Europe for a five-year tour, just as the U.S. was coming into its own as a mature industrial powerhouse and mass cultural exporter.

Bailey transported the entire three-ring behemoth to England by ship. The parade alone dazzled European audiences so thoroughly that many went home afterwards mistakenly thinking they had seen the entire show. In Germany, the Kaiser’s army followed the circus to learn its efficient methods for moving thousands of people, animals, and supplies. Bailey included patriotic spectacles reenacting key battle scenes from the Spanish-American War in a jingoistic advertisement of America’s rising global status.

Bailey’s European tour was a spectacular success, but his personal triumph was fleeting. He returned to the United States in 1902 only to discover that the upstart Ringling Brothers now controlled the American circus market.

When Bailey died unexpectedly in 1906, and the Panic of 1907 sent financial markets crashing shortly thereafter, the Ringlings were able to buy his entire circus for less than $500,000. They ran the two circuses separately until federal restrictions during World War I limited the number of railroad engines they could use. Thinking the war would continue for many years, the Ringlings decided to consolidate the circuses temporarily for the 1919 season to meet federal wartime regulations.

The combined show made so much money that the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s Circus became permanent—known as “The Greatest Show on Earth”—until earlier this year, when, after 146 years, it announced it would close.

Janet M. Davis teaches American Studies and History at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of The Gospel of Kindness: Animal Welfare and the Making of Modern America (2016); The Circus Age: American Culture and Society Under the Big Top (2002); and editor of Circus Queen and Tinker Bell: The Life of Tiny Kline (2008).

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Sara Catania.

Add a Comment