When Kansas Was America’s Napa Valley

Before Prohibition, German Immigrants Created a "New Rhineland"

A booth for the White Tail Run Winery at a farmers' market in Overland Park, Kansas. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Located in the northeastern corner of Kansas, Doniphan County’s eastern edge is shaped like a jigsaw puzzle piece, carved away by the flowing waters of the Missouri River. The soil is composed of deep, mineral-rich silty loess and limestone, making it ideal for farming—and, it turns out, for growing grapes and making wine.

California wasn’t always America’s winemaking leader. During the mid-19th century, that distinction went to Kansas and neighboring Missouri, where winemakers and grape-growers led the U.S. wine industry in production. Bold entrepreneurs, industrious Kansas farmers—many of them German-speaking immigrants—produced 35,000 gallons of wine in 1872. That volume jumped more than six-fold by the end of the decade.

But the growth in Kansas’ wine industry (and its sister industry, brewing) coincided with dramatic changes in the state. From 1860 to 1880, Kansas’s population mushroomed from 107,206 to nearly one million people. Kansans battled over slavery in the Kansas-Missouri Border War (1854-1861) and again during the Civil War (1861-1865). Kansas vintners faced a dynamic and challenging moral, social, business, and political climate. The region’s civic and religious leaders railed against the use of alcohol, which they believed contributed to moral decay and spiritual rot, leading them to implement the first statewide prohibition on selling and manufacturing alcohol in the United States in 1881. For more than a century, this ban caused a slowdown from which the Free State’s winemakers are only now beginning to emerge.

For centuries, Wild Catawba, Concord, Norton, and other grapevines thrived, uncultivated, in the rich soil of the territory. When the explorer Étienne de Veniard de Bourgmont ventured to northeastern Kansas in 1724, Indians supplied his expedition with wild grapes from the Missouri River bluffs, which the captain and his men used to make wine. 80 years later, Lewis and Clark encountered summer and fall grapes at the very same site.

Several thousand German-speaking immigrants who settled nearby in the mid-19th-century sought a “new Rhineland,” a fresh start that offered religious freedom, economic opportunity, and refuge from political and military turmoil in their homelands. These immigrants not only brought large numbers of people, but also cash to foster trade in emerging frontier towns and the know-how to grow grapes and produce wine. Several skilled winemakers and vineyard nurserymen came to Doniphan, Kansas, from Deidesheim, a town in the German Palatinate region known for its winemaking and viticulture since the 13th century. Hardworking and entrepreneurial, they transformed small-scale farm vineyards and wineries into a burgeoning industry.

Winemaker Adam Brenner emigrated from Deidesheim and settled in Doniphan in 1857. As proprietor of Doniphan Vineyards, he manufactured native wines and brandies that were known “world-wide” for their “medicinal qualities.” According to William G. Cutler’s History of the State of Kansas, Brenner’s vineyards spanned 50 acres and had their own cellars, press houses, warehouses, bottling, and packing rooms. One cellar, used for sales, could hold 30,000 gallons of various wines. Two more cellars stored an additional 30,000 gallons each. Later his brother and his nephew both opened vineyards producing thousands of gallons of wine annually, some of it for sacramental use.

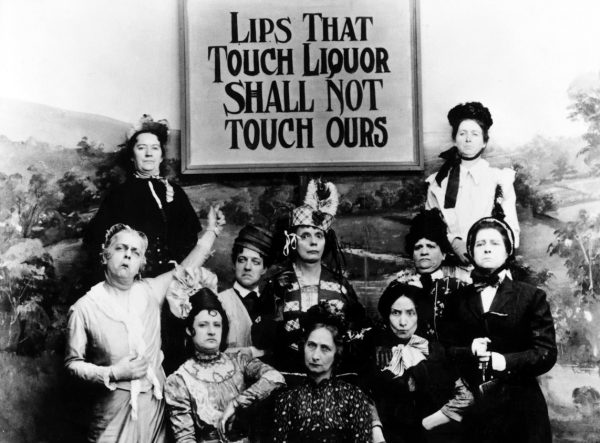

Still photograph of teetotaler women from the satirical short film Kansas Saloon Smashers (1901), which spoofs the Wichita temperance activist Carrie Nation. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

No records indicate what the Brenners’ wines tasted like. Since they were commonly sold for medicinal and sacramental purposes, and sugar was an expensive commodity, the wines were likely dry, sweetened only by natural sugar from the grapes. But whatever their aesthetic qualities, they were clearly highly-regarded. By the early 1880s, vineyards in and around Doniphan produced one million pounds of grapes and 75,000 gallons of wine every year. They grew 24 varieties of native American and American-bred grapes and shipped wine to customers in Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Colorado, Texas, Michigan, and Montana by steamboat and later by rail.

Other parts of Kansas produced wine, too. In A History of Wine in America, a definitive account of winemaking in the United States, author Thomas Pinney noted that a man named A.M. Burns established a nursery specializing in grapevines in Riley County, west of Topeka, in 1856. Within a decade, Burns’ catalog offered more than 150 grape varieties to farmers, including many that he had bred and developed himself.

In 1866, Burns wrote with exuberant optimism about the relationship between Kansas and grapes. “I now think I can with safety predict a glorious future for the grape in Kansas,” he boasted. “It is only a matter of time, and some who, when I commenced to test the vine, sneered at the idea, may yet live to see the day when our bluffs will be teeming with millions of dollars of wealth, while they ought to hang their heads with shame at their own ignorance.” For a time, it seemed that his vision would come to pass. In 1880, the Kansas State Board of Agriculture reported that Kansas produced a whopping 226,000 gallons of wine and reached its peak as a leading producer in the industry.

But just as the optimistic prognostications of A.M. Burns and others seemed to bear fruit, a wave of moral and political action unleashed drastic upheaval in the state. Temperance spread west throughout the U.S., fueled by organizations such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. During its early statehood and explosive population growth, Kansas was awash with wineries, breweries, and saloons—as well as large numbers of gamblers and prostitutes who frequented them. Prohibition proponents, especially women, loathed the lawlessness and vice. Men who drank had a reputation for being abusive, and poor providers. By 1855, the Kansas Territorial Legislature passed a law “to restrain dramshops and taverns, and to regulate the sale of intoxicating liquors.” Citizens voted in special elections on local liquor laws. And in 1871, even the Kansas State Horticultural Society had initiated discussions against the use of grapes for winemaking in the state.

Prohibition also appealed strongly to evangelical Kansans who viewed alcohol as an obstacle toward gaining eternal salvation—and who regarded the German winemakers, some of whom were Catholic, with suspicion. By the late 1870s, Kansans regularly heard anti-alcohol rhetoric at church revivals. Many were swayed to the temperance cause by the fiery, religion-fueled oration of reformed drunk Francis Murphy of Portland, Maine, who addressed a large crowd in August 1879 at a national temperance rally at Bismarck Grove, near Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas Women’s Christian Temperance Union president Drusilla Wilson, who was present at the rally, also won many converts to the cause. An indefatigable speaker and advocate, driven by her Quaker beliefs, she traveled 3,000 miles across Kansas by carriage to enlist support for state Prohibition. She organized 13 temperance unions, led efforts to obtain petition signatures for a prohibitory state amendment, and later worked to ensure the legislature passed the amendment in a general election.

In an address to the state legislature in January 1879, Governor John P. St. John framed temperance as an economic, moral, and social issue. “Could we but dry up this one great evil that consumes annually so much wealth, and destroys the physical, moral and mental usefulness of its victims,” he suggested, “we would hardly need prisons, poorhouses, or police.”

Kansas amended its state constitution on November 2, 1880 to prohibit “the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors … except for medical, scientific and mechanical purposes.” The statute went into effect from in May 1881 and preceded national Prohibition by four decades. Most Kansas winemakers, brewers, and other alcohol manufacturers went out of business. Some relocated across the state line to Missouri. As late as 1900, 20 years after state Prohibition, grape growers in Kansas continued to cultivate thousands of acres of grapes, selling them to bootleggers in Kansas or to winemakers working legally in Missouri, or for consumption as fruit.

In 1866, Burns wrote with exuberant optimism about the relationship between Kansas and grapes. “I now think I can with safety predict a glorious future for the grape in Kansas,” he boasted.

A temperance poster, circa 1903, claimed that Kansas “reduced the annual consumption of intoxicants from the U.S. average of 16 gallons per capita” to less than two, that the state saved an average of more than $6 million “which otherwise would go to the saloon,” and that Prohibition saved annually “more than 1,200 persons from drunkards’ graves.”

Of course, Prohibition—in Kansas and throughout the United States—did not result in a more morally-driven society. The law unintentionally spawned criminal activity by bootleggers and their customers, and ultimately lost support during the Great Depression. National Prohibition was repealed in 1933. In Kansas, too, people drank. But the state remained officially dry, with its voters in 1934 vanquishing a proposed state constitutional amendment that would have legalized alcohol use. Kansas didn’t repeal statewide prohibition until 1948. Some counties still do not allow liquor sales.

Kansans haven’t exactly raced to revive the state’s wine industry. With the earlier generations of winemakers long gone, and the state’s lingering moral and political distaste for alcohol persistent, there was little incentive for investments in new vineyards or wineries. Meanwhile, grape-growing and winemaking have flourished in Missouri.

In the mid-1970s, a horticultural research center near Wichita conducted experiments on soil and climate, and planted trial grapevines with promising results. Encouraged, Dr. Robert Rizza of Halstead, Kansas, planted a vineyard in 1978 and began advocating for the passage of a law that would allow farms to again produce wines on site. In 1983 the state legislature finally approved a farm winery law and amended it in 1985 to reduce costly fees and to permit tastings and sales at wineries as well. The state Department of Agriculture established an advisory program on viticulture and enology, and Kansans began to apply for official licenses and established wineries.

Two decades later, 13 licensed farm wineries in Kansas were harvesting 170 total acres of grapes to produce 50,000 gallons of wine. By 2010, wine production had more than doubled to 107,419 gallons. Today winemakers throughout Kansas plant native and hybrid grapes in the same mineral-rich soils that their 19th-century forebears once so fruitfully worked, producing an impressive range of wines from French-American hybrid and native grapes. A long-abandoned way of life, practiced by some of the state’s first frontier entrepreneurs, is on the rise again.

Pete Dulin is the author of Expedition of Thirst: Exploring Breweries, Distilleries and Wineries Across Central Kansas and Missouri, and Kansas City Beer: A History of Brewing in the Heartland. He lives in Kansas City, Missouri.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown | Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli.

Add a Comment