On the same morning that Abraham Lincoln died from an assassin’s bullet, noted abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was quietly gloating by the Charleston, South Carolina graveside of John C. Calhoun. Garrison, approaching his 60th birthday, had traveled down to secession’s birthplace with a delegation led by the former Union commander at Fort Sumter, now Major General Robert Anderson, in order to help mark the end of the Civil War with a symbolic flag-raising ceremony at the heavily damaged harbor fortifications where the shooting had begun.

Early on the morning of April 15, 1865, Garrison, best known as the controversial editor of The Liberator, had traveled across the city with a handful of other fellow abolitionists to visit the gravesite of the original philosopher of secession. Sometime shortly after Lincoln had choked out his last breath at 7:22 a.m., Garrison reportedly said to his friends standing inside the cemetery, “Down into a deeper grave than this, slavery has gone, and for it there is no resurrection.”

The trouble was that not everybody agreed with Garrison’s optimistic prediction. The end of the war and the pending destruction of slavery was generating a deep sense of foreboding among many Americans, only magnified that Saturday afternoon as word of Lincoln’s assassination spread across the nation’s telegraph lines.

On April 14, 1865, the U.S. flag was raised again over Fort Sumter

Frederick Douglass, the most famous black abolitionist in the country, certainly lacked Garrison’s confidence about the future. Douglass had not gone with the others to Charleston to commemorate victory, but had instead been out lecturing northern audiences on the remaining work to be done to secure real freedom for the former slaves. He was at home in Rochester, New York, when word of the president’s murder reached him, and that evening he delivered some impromptu remarks at a hasty memorial held at city hall. Much later, he claimed that this moment was the first time he had ever felt such “close accord” with his white neighbors. It was the shocking nature of that “terrible calamity,” he recalled, which made them all—white and black—feel more like “kin” than “countrymen.”

This was an especially important sensation for Douglass, because he was already deeply concerned that emancipation would mean little without immediate and full equality. He had been arguing for months that friends like Garrison, his one-time mentor and patron, might ultimately fail the former slaves if they did not push harder for black rights while black men and women were still making important contributions to the Union war effort.

Garrison and his clique of mostly white supporters were not opposed to black voting rights or other civil rights, but they had different priorities by April 1865. They were busy that spring organizing emergency charitable support, what they called freedmen’s relief, spurred on by the pending creation of the new federal Freedmen’s Bureau. The idea was to provide a safety net and universal education for the former slaves, propelling them toward integration into American society and the labor force. Yet in the weeks after Lincoln’s assassination, Douglass became openly scornful of such efforts, which he considered patronizing and a dangerous distraction. “The negro needs justice more than pity,” he growled on May 2, 1865, “liberty more than old clothes; [and] rights more than training to enjoy them.”

A week later, he went even further and backed a kind of coup within the American Anti-Slavery Society, the great abolitionist organization that Garrison had launched some three decades before. Proud but tired, Garrison had proposed disbanding the movement in its moment of triumph, anticipating ratification of the proposed 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which had passed Congress at the end of January. On May 9, 1865, the resolution to disband was voted down, 118-48, and orator Wendell Phillips replaced the now-outcast Garrison as head of the organization. Douglass supported Phillips and blasted anyone who claimed that slavery was already in its grave. “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot,” he said at the annual meeting in New York, with Garrison glaring down at him, and then adding with a defiant flourish, “or [while] any discrimination exists between white and black at the South.”

Abolitionists had always been prone to feuding, especially over movement tactics, but there was still something maddening about this last epic fight. During a period that should have been marked by a spirit of solemn awe over what they had helped to accomplish, the anti-slavery activists found themselves at worse odds than ever during the final months of the Civil War.

Douglass was in a fighting mood, but he was also a practical man. He soon developed a plan for achieving his most sweeping aspirations. The public’s reaction to Lincoln’s assassination had captivated him, as it did so many others. The electric bond, which he had first felt with his white neighbors on that Saturday evening of April 15, convinced him that the best way forward was to fight this new political war in Lincoln’s name, to keep reminding white audiences that embracing black equality was the best way to honor the martyred president’s memory.

Douglass began this campaign in earnest on June 1, 1865, which had been set aside by new President Andrew Johnson as a national day of mourning for Lincoln. Johnson did not share Douglass’ civil rights fervor, however, and had just issued a controversial proclamation of amnesty, which offered pardons to most of the participants in the Confederate rebellion. This was the kind of backsliding that infuriated Douglass and that he would spend the rest of his life fighting against. So, Douglass eulogized Lincoln that morning in New York emphatically as the “black man’s president,” calling him “the first to show any respect to their rights as men.” He pushed hard to define the war as a struggle not just for emancipation, but also for equality—and did so explicitly in Lincoln’s name. Over the next several years, Douglass pursued this strategy with a single-minded devotion that yielded some impressive results. He made an alliance with Radical Republicans who had come to despise President Johnson and together they fought successfully for the 14th (1868) and 15th (1870) Amendments, which guaranteed equality and due process for all Americans, and suffrage for black men.

But this early civil rights movement also encountered major setbacks. They failed to end discrimination in the South (or North, for that matter), and in their zeal to insist it was “the negro’s hour” and to abolish all the vestiges of slavery, Douglass and Phillips antagonized feminists and old friends like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who wanted a broader expansion of voting rights. By the middle of the 1870s, it was clear that civil rights for blacks had come at a high political cost and that the future of freedom was still as uncertain as ever.

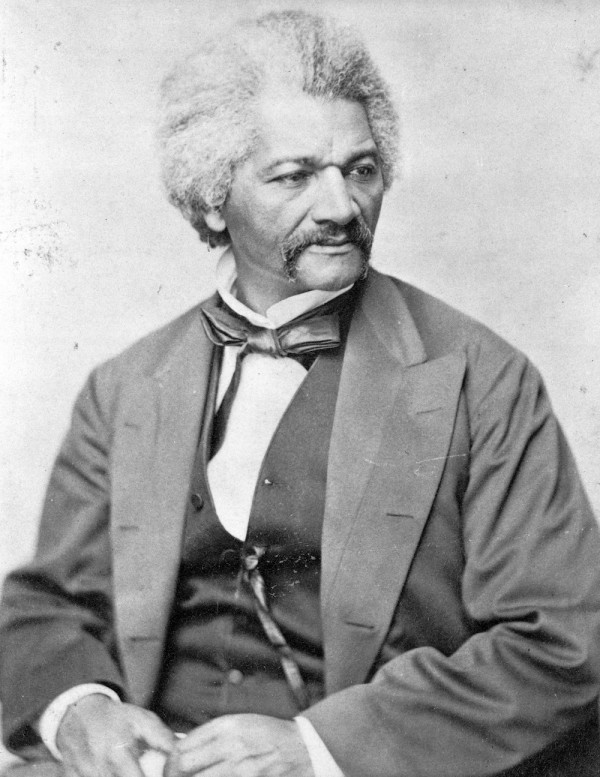

Portrait of Frederick Douglass

On April 14, 1876, the 11th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination, Douglass spoke at the dedication of an emancipation memorial in Washington, D.C. The statue, funded with the contributions from tens of thousands of freed people who organized the effort in the immediate aftermath of the assassination, showed a standing Lincoln unshackling the chains of a kneeling slave. Yet the memory of that magical period when white and black had felt an electric kinship over their martyred president now seemed far removed. Douglass no longer tried to invoke Lincoln as the “black man’s president.” Instead, he now called him “preeminently the white man’s President,” and concluded, with President Ulysses S. Grant and members of the Supreme Court seated behind him, that Lincoln had been “entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.”

The speech was not a total surrender of faith—Douglass still praised Lincoln’s emancipation policy—but it was an admission that his earlier strategy had fallen short. Rallying around Lincoln’s memory had helped to alter the words of the Constitution, but it was not enough to revolutionize American race relations.

Douglass had come to the hard realization that slavery and its vestiges were not fully abolished, even after the black man had the ballot. Not everybody saw it that way, but clearly the fight over what it meant to be an American—a free American citizen—was far more complicated than anyone had anticipated.

is the Pohanka chair of civil war history at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and an Arizona State University future of war fellow at the New America Foundation.

Primary Editor: Andrés Martinez. Secondary Editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

Lead photo courtesy of Library of Congress. Interior images courtesy of Library of Congress and House Divided Project at Dickinson College.

Add a Comment