A Jewish Photographer’s Nearly Forgotten ‘Collaboration’ with Cheyenne Indians on the Santa Fe Trail

The Sole Surviving Image of the Perilous Journey Provides a Crucial Bridge to History

The only surviving daguerreotype from Solomon Nunes Carvalho’s journey West in 1853 depicts a view of the Cheyenne Village at Big Timbers. A pair of figures stand to the left; drying hides hang on the right. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

On a cold day in late November 1853, in a place called Big Timbers, in what is today southeastern Colorado, a Jewish photographer named Solomon Nunes Carvalho hoisted his ten-pound daguerreotype camera onto a tripod and aimed his lens at a pair of Cheyenne Indians. At first glance, the resulting image, scratched and faded from years of neglect, seems unremarkable. But in fact it is probably the oldest existing photograph of Native Americans taken on location in the western United States. It’s the sole surviving daguerreotype from an unprecedented and extraordinary photographic journey. And for me, a filmmaker chronicling Carvalho’s incredible but little-known story, it ultimately provided a powerful spiritual bridge to the past.

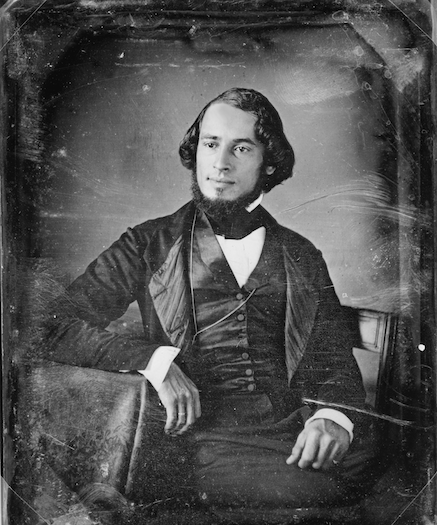

Carvalho was 38 years old and an unknown portrait artist and daguerreotypist when he received an offer from Col. John C. Fremont, the most famous adventurer of the day, to serve as the official photographer of Fremont’s Fifth Westward Expedition. For years, Fremont had been consumed with mapping a route for the transcontinental railroad. He had always included a sketch artist among his crew, but this time he wanted to use photography, a new technology, to document the terrain.

Solomon Nunes Carvalho in 1850. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

It was a risky proposition. Fremont’s previous foray had ended in disaster when ten men froze to death in the Rockies, and Carvalho was totally unprepared. An urbane city dweller raised in Charleston, S.C., he had never traveled West. In fact, he had never even saddled his own horse. No daguerreotypist had ever attempted anything like this before. Daguerreotopy, which was the earliest form of photography, had only been invented fourteen years earlier, in 1839. It was a cumbersome process involving polished silver-coated copper plates and lots of gear and chemicals, and it was prone to failure. Of the handful of professional daguerreotypists in the United States, nearly all worked indoors, shooting portraits. Capturing wide landscapes in extreme weather conditions was almost unheard of.

Yet two weeks after accepting Fremont’s offer, Carvalho set out, with a seasoned group of explorers, teamsters, hunters, and guides. It would be the journey of his lifetime. The team included white Americans, a German, a few Mexicans, ten Delaware Indians, and of course Carvalho, who was an observant Sephardic Jew of Spanish-Portuguese descent. From the very start, the group faced challenges: torrential rains, raging prairie fires, injuries, infighting. Col. Fremont became injured early on, and had to turn back to seek medical attention. After a six-week delay, Fremont rejoined his men in Western Kansas, and then led them, perhaps foolishly, toward the Rocky Mountains just as winter was about to set in.

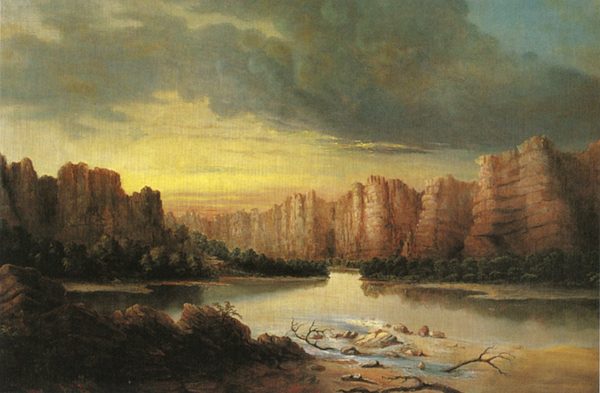

Along the way, Carvalho dutifully worked at his craft and, against the odds, succeeded in capturing image after image of the landscapes, buffalo, and the expansive terrain of the West.

The expedition encountered the Cheyenne village at Big Timbers in late November, during a supply stop along the Santa Fe Trail. It wasn’t easy photographing the Native Americans, Carvalho found. “I had great difficulty in getting them to sit still, or even submit to having themselves daguerreotyped. I made a picture, first, of their lodges, which I showed them,” he later wrote.

Carvalho’s daguerreotype of Big Timbers shows a pair of teepees nestled up against the edge of a forest of tall pines. Atop a thicket of logs and tree branches, several skins or hides are set out to dry. Two human figures, faded to an almost ghostly pallor, anchor the image in time. Their faces are hard to make out, but one has long braids and both are dressed in traditional native outfits.

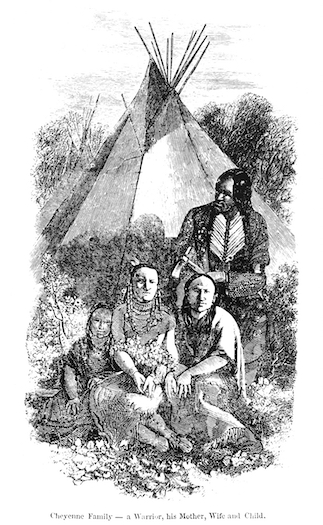

An engraving based on Carvalho’s daguerreotypes.

Princeton historian Martha A. Sandweiss, an expert in photography of the American West, credits Carvalho with creating a painstakingly deliberate scene. “Carvalho sensed he needed to preserve a certain amount of information,” she told me, in an interview. “He stepped back from the scene, and he has carefully framed the image. He’s not doing a close up, at least in this picture, of the two people, or of the teepee, or of a piece of meat on the ground. He’s trying to show us something about native life.”

Fremont was thrilled with Carvalho’s work. “We are producing a line of pictures of exquisite beauty, which will admirably illustrate the country,” he wrote to his wife, Jessie Benton Fremont. He described the pictures of Big Timbers as “jewels.”

Sandweiss believes the daguerreotype tells us as much about the photographer as it does the subject. “I think what we see in this picture is evidence of a collaboration. It’s important to remember that Carvalho was working with a camera on a tripod. This is not a snapshot. These Indian subjects knew they were being photographed, and they are looking Carvalho in the eye.”

Of the 300 or so daguerreotypes Carvalho made on the expedition, this image is the only survivor.

After the expedition, photographer Mathew Brady’s New York studio converted Carvalho’s daguerreotypes into hand-drawn printing plates, so they could be turned into etchings and published. At the time, converting photographs to etchings was the only way to reproduce them for large numbers of people to see. It seems inconceivable to us today, but at that early time in photographic history, the daguerreotypes themselves were considered worthless—just a means for carrying back visual information that would be enshrined forever on a steel printing plate. Years later, they ended up in a storage unit belonging to Fremont, and were destroyed in a fire in 1882—gone forever, and barely missed. The Big Timbers daguerreotype somehow, luckily, ended up in Brady’s personal collection, which now resides at the Library of Congress.

Rio Grande, painting by Solomon Nunes Carvalho. Courtesy of Oakland Museum of California.

The sixty-odd surviving etchings made from Carvalho’s daguerreotypes tell a spectacular story of discovery, but the one surviving image does more: It provides a spiritual connection to the past. For most of the years I worked on my documentary film, Carvalho’s Journey, I relied on various reproductions of the Big Timbers image. I finally had a chance to see the real thing during a visit to Washington, D.C. last year.

It is smaller than I had imagined, just four by five inches. In real life, the damage is worse than in reproductions. But holding it in my hands, I was struck by an intense proximity to history. This piece of copper was the same tool that miraculously captured the Cheyennes’ likenesses, their teepees, their hides drying on the line. It was the same bit of metal that an urbane, Southern-Jewish photographer carried thousands of miles on horseback and heated over a fire to develop. The moment captured on the plate, faded as it is, was the exact image Solomon Carvalho saw that day. Native people who had never seen a photograph before—and whose lives would never be the same after their collision with Europeans—would have seen it too. It was the vessel through which an unlikely visitor and a pair of Indians faced each other and forged a quintessentially American encounter.

Daguerreotypes, which are in many ways an art form lost to history, are reflective just like mirrors. On one as faded as Carvalho’s, the mirrored surface makes it almost impossible to see the image detail when you look directly at it. You instead see yourself, peering into it, looking into history.

Steve Rivo is a documentary filmmaker and television producer. He is the writer and director of Carvahlo’s Journey, which has shown in over two dozen film festivals worldwide. On January 30 and 31, the film will screen in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Theatres. In spring 2017, the film will be released on DVD/VOD. More info at www.carvalhosjourney.com.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Reed Johnson.

Add a Comment