The Civil War General Whose Godly “Mission” Went Astray

Oliver Otis "Uh Oh" Howard Was a Crusader for Ex-Slaves and a Scourge of Native Americans

Caricature from Puck showing Gen. Oliver Otis Howard chasing an Indian around a rock; Aug. 7, 1878. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

When God first visited him in 1857, Oliver Otis Howard was a lonely army lieutenant battling clouds of mosquitoes in a backwater posting that he described as a “field for self-denial”: Tampa, Florida. Howard had spent his life swimming against powerful tides. Ten when his father died, he had to leave his family in Leeds, Maine, and move in with relatives. Through constant study, he made it to Bowdoin College at age 16, graduating near the top of his class and earning a commission to West Point. Bare-knuckling his way to respect, he finished fourth in his class—only to begin his climb anew as a junior officer.

Sent a thousand miles away from his wife and baby boy, Howard found it hard to see the point of all the effort and sacrifice. But at a Methodist meeting, “the choking sensation” suddenly lifted, replaced, he wrote, by “a new well spring within me, a joy, a peace & a trusting spirit.” God had found him—had “pluck[ed] my feet from the mire & place[d] them on the rock”—for a reason. Howard was 26 years old, and something meaningful awaited him.

The idea that something important is in store for us is a deeply American faith, rooted in Cotton Mather’s examinations of “God’s providence” in the New World and extending to evangelical pastor Rick Warren’s popular attempt to answer the question, “What on earth am I here for?” But this source of strength has a sharp edge. Oliver Otis Howard’s life forces us to ask: What do we do when our grand sense of purpose does not last—or, worse yet, fails us?

Howard returned north to teach math at West Point after his stint in Tampa ended. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 made the Union his calling. “I gave up every other plan except as to the best way for me to contribute to the saving of her life,” Howard wrote.

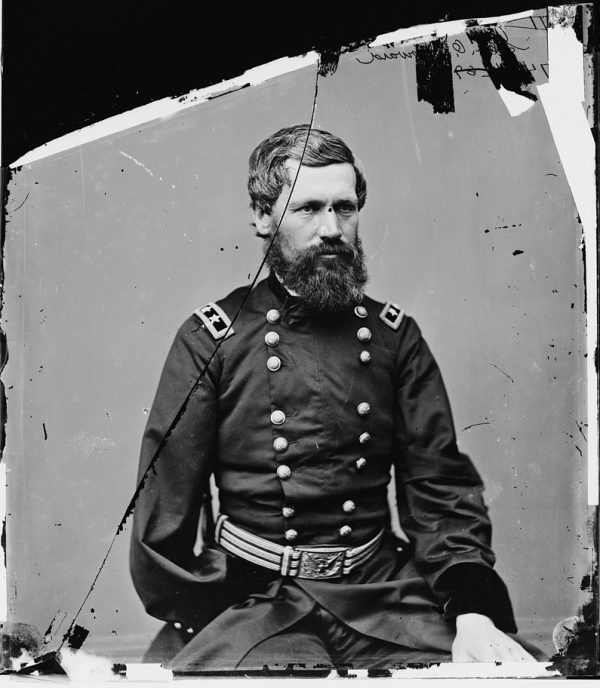

Photo portrait of Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, between 1860 and 1865. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Once again, Howard would struggle. He was quickly promoted to brigadier general, but lost his right arm in battle in June 1862. He returned to the fight at summer’s end, only to experience a year of humiliating battlefield defeats. In a play on his first two initials, his men started calling him “Uh Oh” or “Oh Oh” Howard.

Through it all, Howard found a new divine purpose in the heroism and daring of the black men, women, and children who crossed army lines, proclaiming themselves free after lives of bondage. Not much of an abolitionist before the war—to his soldiers’ displeasure, his main cause had been temperance—Howard wrote a letter to the New York Times on January 1, 1863, proclaiming, “We must destroy Slavery root and branch … This is a hard duty—a terrible, solemn duty; but it is a duty.” Howard’s abolitionism earned him allies in Congress, helping him hold onto his command long enough to be sent west to fight under William Tecumseh Sherman. He finally distinguished himself in the Atlanta campaign and played a key role in Sherman’s March to the Sea.

As the war was ending in May 1865, Howard was called to Washington and asked to lead the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, an agency created by Congress to provide humanitarian relief for the South and shepherd some four million people from slavery to citizenship. It was a new experiment in governing, the first big federal social welfare agency in American history. Howard saw the opportunity as heaven sent. Howard, then 34 years old, embraced the cause of the freed people as the mission that would guide the rest of his life.

Howard soon realized that the government had no capacity to change white Southerners who were, in essence, still fighting the Civil War, and he lacked the political and administrative savvy to execute policies such as land redistribution that would have upended the political, economic, and social dynamics of the South. So Howard poured Bureau resources into education, which he called “the true relief” from “beggary and dependence.” When a new institution of higher education for black men and women was chartered in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1867, it was almost a given that it would be named for the crusading general. Howard University would be a monument to Reconstruction and to its fragility—to the knowledge that its promise and values were always under threat.

Accused of corruption and nearly bankrupted by lawyers’ fees, Howard described himself as “crippled & broken” by his failures. His calling had become a cruel mirage. Still, Howard remained convinced that he had been chosen to lead a meaningful life.

In time, Howard’s successes during Reconstruction were overwhelmed by his defeats. He became a lightning rod for Reconstruction’s enemies, who attacked the very notion that government should devote itself to liberty and equality for all. The Freedmen’s Bureau lost most of its funding after 1868 and folded in 1872. Accused of corruption and nearly bankrupted by lawyers’ fees, Howard described himself as “crippled & broken” by his failures. His calling had become a cruel mirage. Still, Howard remained convinced that he had been chosen to lead a meaningful life. “God in his mercy has given me much recuperative energy,” he wrote at the time. “I know better than to quarrel with his dealings with me.”

In 1874, Howard’s faith drove him west. Cleared of corruption charges, he rejoined the active-duty military and assumed command of army forces in the Pacific Northwest. It was a willing exile. Far from the capital, he was convinced that he could restore his reputation and find a way back to power and purpose. A big part of Howard’s job involved convincing Native Americans to move to reservations and establish themselves as farmers on small plots of land. He believed he was saving them from genocide, leading them down a path to citizenship—if only they would agree to be led.

In September 1876, just months after the slaughter of Custer’s army at the Battle of Little Bighorn, Howard announced that a land dispute between white settlers and Nez Perce Indians in Oregon and Idaho could become the next bloody flashpoint. He offered himself up as the man who could resolve the situation. Democratic and Republican newspapers agreed that he was uniquely capable of convincing the Indians to move to an Idaho reservation peacefully. Howard’s redemption was at hand.

Howard appealed to a Nez Perce leader known as Chief Joseph to cede his ancestral territory and move to the reservation. But Joseph refused. “This one place of living is the same as you whites have among yourselves,” Joseph argued, asserting his right to the property and assuring Howard that his people could live peacefully alongside whites, as they had since the first settlers came onto his land five years earlier. It was a plea for sovereignty, but also for liberty and equality, echoing the same values Howard had championed a decade before. This time, Howard’s drive to fulfill his mission pushed aside such principles.

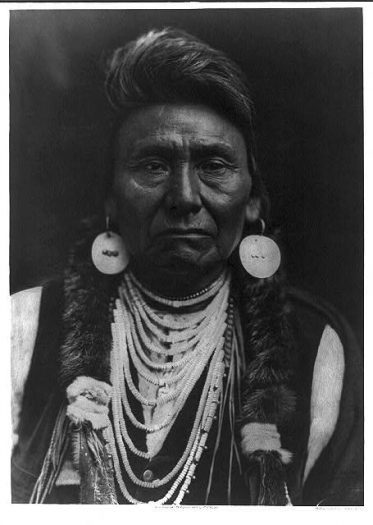

Undated photo portrait of Chief Joseph-Nez Perce, by Edward S. Curtis. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In May 1877 the general demanded that all Nez Perce bands move onto the reservation within 30 days, forcing them to risk their herds by crossing rivers during the spring flood. The ultimatum all but assured violence. On the eve of the deadline, a group of young warriors committed a series of revenge killings, targeting settlers along the Salmon River. After the bloodshed started, Howard and his troops pursued 900 or so men, women, and children across Nez Perce country, through the Northern Rockies, and over the Montana plains.

The Nez Perce bands outran the soldiers for three and a half months. When troops riding ahead of Howard managed to catch the families by surprise in August 1877, they massacred women and children, but still failed to end the war. While Howard gave chase, the glory he craved slipped his grasp. Newspapers ridiculed him for not capturing Joseph. Settlers along the way gave him a cold reception. His superiors moved to strip him of his command.

Joseph’s surrender in October 1877 brought Howard little relief. Joseph’s battlefield declaration, “I will fight no more forever,” almost immediately made him a figure of national fascination—a noble warrior who protected women and children and whose pleas for liberty and equality felt deeply patriotic. There was no satisfaction in crushing the man widely described as “the best Indian.”

Howard finished his military career with a series of quiet postings, waiting—too long, he thought—for his promotion to Major General. In retirement, he briefly found a new calling, leading efforts during the Spanish American War to evangelize soldiers and sailors and keep them out of bars and brothels. In the early 1900s, with memories of Reconstruction dimming, Howard was hailed as an exemplar of the Union cause, described by Teddy Roosevelt as “that living veteran of the Civil War whom this country most delights to honor.”

But praise was not the same as purpose, and for Howard, a grand redemption remained elusive. He spent the last three decades of his life justifying his conduct in the Nez Perce War. At the same time, some of his work constituted an admission of wrongdoing, however subtle; his official reports and three books played a crucial role in making Joseph a celebrity and leading figure of dissent in late 19th-century America.

In allowing Joseph’s legend to eclipse his own, Howard promoted a man whose pleas to be “free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself” connected the Reconstruction-era values that had once inspired a young man of faith with a new century’s struggles for civil rights and civil liberties. Howard’s work was meaningful in the end. But he was not the hero of his own story.

Daniel Sharfstein, who teaches law and history at Vanderbilt University and was a 2013 Guggenheim Fellow, is the author of Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War.

Primary Editor: Eryn Brown. Secondary Editor: Joe Mathews.

Add a Comment