Suddenly, it seems, the camera has become a potent weapon in what many see as the beginning of a new civil rights movement. It’s become a familiar tale: Increasingly, blacks won’t leave home without a camera, and, according to F.B.I. Director James B. Comey, more police officers are thinking twice about questioning minorities, for fear of having the resulting film footage go viral.

But the link between photography (or film) and civil rights dates back to Frederick Douglass, the famous former slave, abolitionist orator and writer, and post-war statesman.

Douglass was in love with photography. He wrote more extensively on the medium than any peer. He frequented photographers’ studios and sat for his portrait whenever he could, especially while on the road, which was most of the time. He became the most photographed American in the 19th century.

Douglass considered photography the most democratic of arts, a crucial aid in the quest to end slavery and achieve civil rights. He called Louis Daguerre, the founder of the first popular form of photography still renowned for its luminous detail, “the great discoverer of modern times.” With Daguerre’s invention, known to us as the daguerreotype, “the humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase 50 years ago.” Photography dignified the poorest of the poor; it was a potent equalizer.

Douglass and photography grew up together. He escaped from slavery in 1838, a year before Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot created the first forms of photography. He began his career as an abolitionist orator in 1841, just as technical improvements reduced exposure times, enabling the proliferation of daguerreotype portraits. Portraits fueled the demand for photography and constituted over 90 percent of all images in the medium’s first five decades.

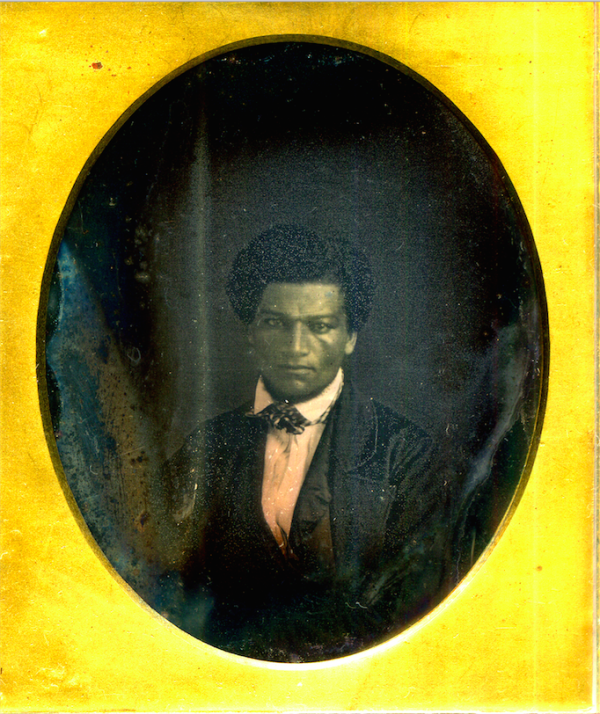

Daguerreotype, ca. 1841. Collection of Greg French.

Douglass first sat for his “likeness,” as daguerreotypes were often called, around 1841, at the beginning of his public career. By the end of the decade, following his extraordinary success as an orator and autobiographer, he was famous at the very time photography had become hugely popular. There were photographic studios in every city, county, and territory in the free states. Virtually every Northerner could afford to have his or her portrait taken. Engravings, cut from these photographs, circulated as illustrations in best-selling books, including Douglass’s, and in the press, enabling readers to receive the news visually for the first time.

Douglass recognized the power of photography. He and many other Americans believed that Mathew Brady’s photograph of Lincoln, taken in February 1860, helped elect him. At the time, Lincoln’s candidacy was a long shot, as he was virtually unknown in the east. After Brady’s photograph circulated widely in newspapers and became ubiquitous during the campaign, Lincoln purportedly said that Brady’s portrait had elected him. Douglass said the same thing: “The portrait makes the president.”

![“Hon. Abram Lincoln, of Illinois, Republican Candidate for President. [Photographed by Brady],” Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1860, Cover.](https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Image-4.png)

“Hon. Abram Lincoln, of Illinois, Republican Candidate for President. [Photographed by Brady],” Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1860, Cover.

Douglass associated photography with freedom, and the feeling was shared by many across the nation’s free states who embraced photography with a fervor that surpassed that of every other nation on earth. The more rural southern slave states, however, were slower to embrace the medium. Defensive about slavery, white Southerners seemed to tacitly agree that there was much about their society best left un-illustrated.

Douglass defined himself as a free man and citizen as much through his portraits as his words. He also believed in photography’s power to convey truth. Even more than truth-telling, the truthful image represented abolitionists’ greatest weapon, for it exposed slavery as a dehumanizing horror. Photographic portraits bore witness to blacks’ essential humanity, countering the racist caricatures evident in lithographs and engravings based on drawings.

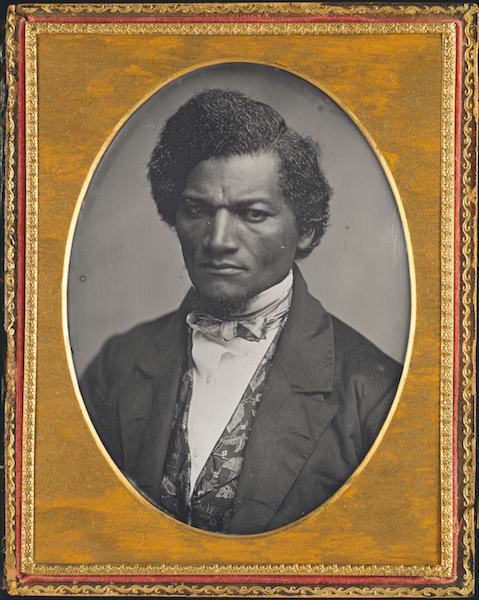

Douglass’s portraits and words sent a message to the world that he had as much claim to citizenship, with the rights of equality before the law, as his white peers. This is why he always dressed up for the photographer, appearing “majestic in his wrath,” as one admirer said of a portrait from 1852, and why he labored to speak and write with such eloquence. Through his images and words, he sought to “out-citizen” white citizens, at a time when most whites did not believe that blacks could be worthy citizens.

Samuel J. Miller, Frederick Douglass, 1852, Daguerreotype. Art Institute of Chicago.

The sheer number of Douglass portraits—160 separate poses, reproduced millions of times—conveys not only his faith in photography, but his understanding of the public identity he was crafting. Photographers sought Douglass out and loved working with him. One friend boasted that she “owned more than 20 pictures of him,” and described how “the photographers are running after him to sit for them.”

Douglass would have been a savvy social media devotee, as he continually updated his public persona, projecting a continually evolving self. By doing so, he was defying the static foundations of both slavery and racism, which are predicated on the idea that some people of a certain race are somehow immutably inferior to others. Douglass’s fluid conception of the self united art and politics. He went so far as to say that “the moral and social influence of pictures” was more important in shaping national culture than “the making of its laws.”

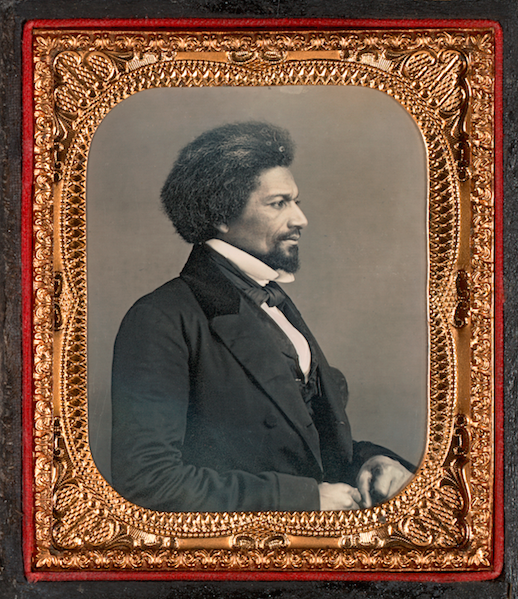

His portraits evolved over the years from revolutionary freedom fighter and steely visionary to wise prophet and elder statesman. The most noticeable visual marker of his continual evolution is his facial hair and hairstyles. While 19th-century men experimented with hirsute faces, few did so as frequently as Douglass. He tracked, and often led, the prevailing fashion.

Sixth-plate Daguerreotype, ca. 1855. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

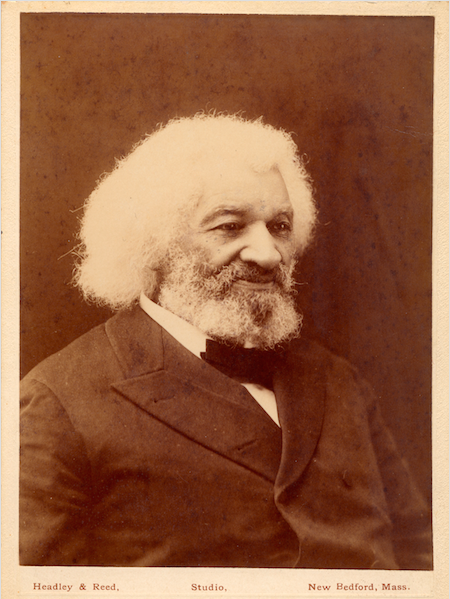

Among the 160 distinct Douglass poses, two continuities stand out. First, he almost never showed a smile, with the notable exception of an 1894 cabinet card, a popular post-war format that resembled a large postcard, six months before he died in 1895. Almost to the end of his life, he refuted the racist caricatures of blacks as happy slaves and servants. Second, he presented himself, in dress, pose, and expression, as a dignified and respectable citizen. Douglass’s portrait gallery contributed to his persona as one of the nation’s preeminent “self-made men,” the title of one of his signature speeches.

Phineas Headley, Jr. and James E. Reed, Cabinet Card, 1894. New Bedford Whaling Museum.

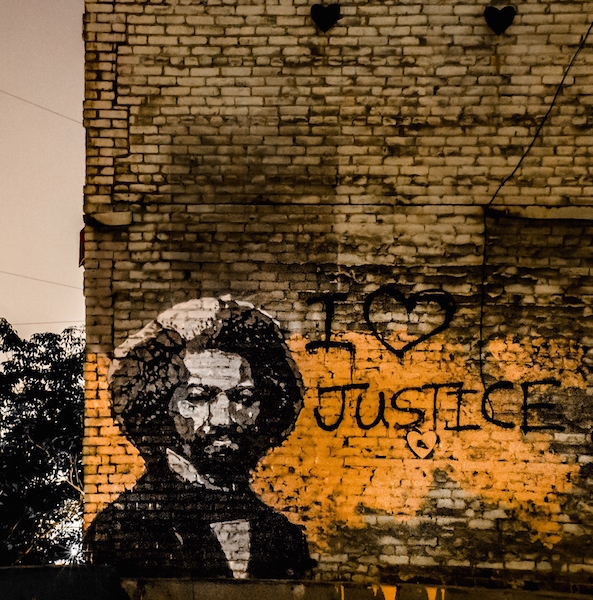

Nowadays, his portraits serve as an important visual legacy. In the thousands of murals, sculptures, paintings, prints, drawings, postage stamps, and magazine covers based on Douglass’ photographs, his face and demeanor broadcast a protest against lynching and segregation. It has lobbied for civil rights and celebrated Black Power. It dignified the black body that white Americans, according to Ta-Nehisi Coates, have so often tried to destroy.

St. George, Frederick Douglass, Los Angeles, CA, 2013.

Douglass was astute in his awareness of the potential of photography to shape public opinion and change society, and so it’s fitting that this great American’s “likeness” has fought on for his worthy causes long after the man himself had passed on.

is a professor of English and African and African-American Studies at Harvard and the author of the prize-winning The Black Hearts of Men. His new book, co-authored with Zoe Trodd and Celeste-Marie Bernier, is Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the 19th Century’s Most Photographed American

Primary editor: Andrés Martinez. Secondary editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

*Lead photo by John C. Buttre, Frontispiece to Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom. Collection of John Stauffer. Interior photos courtesy of John Stauffer.

Add a Comment